How a repair ship captain received the Medal of Honor at Pearl Harbor

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 had drama aplenty to go around, but one of the standouts did not involve a battleship, but a humble repair ship moored nearby. Capt. Cassin Young’s actions that day gave a new meaning to the slogan “Don’t give up the ship,” though later, aboard a heavy cruiser, he would carry those words to a watery grave.

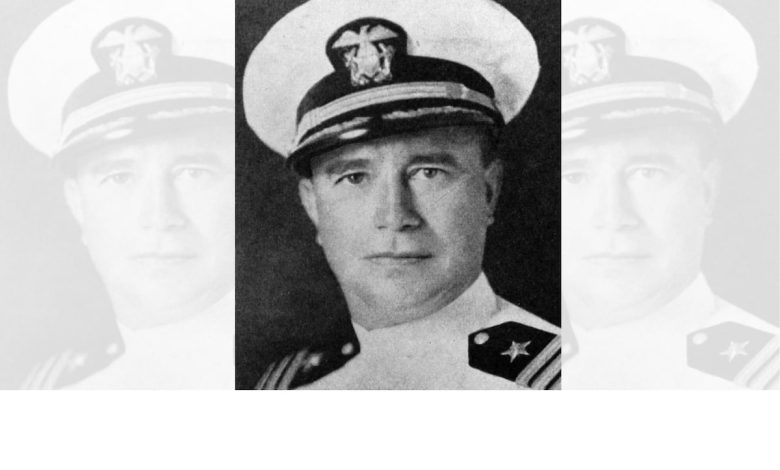

Young was born in Washington, D.C. on March 6, 1894 and his choice of a naval career carried him through to graduation at the U.S. Naval Academy in June 1916. After entering service on the battleship Connecticut in 1919, he served aboard submarines R-23 and R-2 to herald a career frequently involving the submersibles. After serving in the Eleventh Naval District from 1935 to 1937, he commanded Submarine Division Seven at New London and Groton, Connecticut.

On Dec. 6, 1941, Young commanded the repair ship Vestal, which he fatefully brought alongside the battleship Arizona. The next day, he found his vessel under air attack, hit by two Japanese bombs and debris from Arizona when it exploded. Young’s citation described his extraordinary actions thereafter:

“Young proceeded to the bridge and later took personal command of the 3-inch antiaircraft gun when blown overboard by the blast of the forward magazine explosion of the U.S.S. Arizona, to which the U.S.S. Vestal was moored. He swam back to his ship. The entire forward part of the U.S.S. Arizona was a blazing inferno with oil afire in the water between the two ships; as a result of several bomb hits, the U.S.S. Vestal was afire in several places, was settling and taking a list. Despite the severe enemy bombing and strafing at the time, and his shocking experience of having been blown overboard, Commander Young with extreme coolness and calmness, moved his ship to an anchorage distant from the U.S.S. Arizona and subsequently beached the U.S.S. Vestal upon determining that such action was required to save his ship.”

While climbing back aboard Vestal, Young noticed some of his men abandoning ship, but stopped them with shouts of “Come back! We’re not giving up this ship yet!” Noting that the after section of his ship was flooding, he hailed a passing tugboat to help maneuver Vestal clear of Battleship Row, to finally be beached at Aiea Shoal.

For his conspicuous gallantry Young was awarded the Medal of Honor for “distinguished conduct in action” at Pearl Harbor.

Promoted to captain and given the command of the heavy cruiser San Francisco in February 1942, Young went on to take part in the battles that began turning the naval tide in the Pacific, including the nocturnal Battle of Cape Esperance on Oct. 11-12 and the carrier clash at Santa Cruz on Oct. 26. This led to the three-day climax of the naval battles at Guadalcanal.

On the night of Nov. 12, Japanese Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe led a naval force, to bombard Henderson Field. Centered around the 27,500-ton battleships Hiei and Kirishima, his force also consisted of one light cruiser and 11 destroyers.

Advancing to meet them was a scratch force commanded by Rear Adm. Daniel J. Callaghan. Arranged in a single column of destroyers and light cruisers, a few had the latest screen grid radar, although none of those was deployed up front.

The first of two critical naval engagements began with the opposing vanguard destroyers passing one another in the night. It ended the next day with the Americans losing light cruisers Atlanta and Juneau and destroyers Barton, Cushing, Laffey and Monssen, while the Japanese lost destroyer Akatsuki and battleship Hiei.

Both commanding admirals were in the thick of the action.

Early on, Hiei’s 14-inch guns blew away San Francisco’s fore turrets. Responding to a message that his flagship was firing in error on the USS Atlanta, on which Rear Adm. Norman Scott had been killed, Callaghan signaled “Cease firing own ships.”

His ship, however, had also been firing on destroyer Akatsuki, which after hitting Atlanta with two torpedoes, was caught in a lethal crossfire from Atlanta, San Francisco and O’Bannon, and sank with nearly all hands.

Moments later, San Francisco was hit by more than a dozen shells from the Japanese Kirishima and destroyers Inazuma and Ikazuchi, killing Callaghan and almost all of his staff —including Young.

Kirishima was grazed by only one 8-inch shell, but retired on Adm. Abe’s orders. Although in a position to deliver the coup de grace to his American opponents, the Japanese admiral, wounded and understandably shaken by the confusion and devastation around him, ordered his battleships to turn for home.

Hiei, slow on its northward run, was hit by 50 shells, including some from San Francisco’s rear battery and Portland’s forward turrets. As it painfully crawled northward, an internal boiler collapse ground Hiei to a halt.

By dawn most ships that could were retiring. The destroyer Aaron Ward lay dead in the water.

Yudachi, its crew evacuated by Samidare, lay burning along with the abandoned hulks of American destroyers Cushing and Monssen. Hiei, unable to move, lay off Savo Island with Yukikaze standing by to assist or evacuate.

Portland, steaming in circles, paused for an attempt at self-repair and then, as its path brought it within range of Yudachi, finished off the destroyer with an 8-inch salvo.

At 1100 hours, torpedo wakes crossed San Francisco’s bow, launched by submarine I-26. A minute later one of them struck the previously torpedoed Juneau with cataclysmic results — all but 10 of its 700 crewmen, including the famous five Sullivan brothers, were lost in the ensuing magazine explosion.

Later, the tug Bobolink came up from Tulagi to take Aaron Ward in tow. This stirred a response from Hiei’s gunners, 13 miles away, which in turn drew a counter response from Henderson Field, the target that Adm. Abe had failed to neutralize the night before.

Now its U.S. Marine Corps bombers dealt his flagship such damage that Abe gave up trying to save it. After Yukikaze evacuated the crew, Hiei went down stern-first, the first Japanese battleship loss of World War II.

Elsewhere, Atlanta edged its way to Kukum to land its survivors. Judged beyond salvaging, it too was scuttled.

It had been a calamitous night for the Americans in terms of men and ships, but the grim sacrifice of Callaghan and Scott— who were both awarded posthumous Medals of Honor — had won the strategic victory by protecting Henderson Field and the reinforcements from the enemy guns.

Far more, however, had been won than an airfield and the lives of soldiers. That night and on Nov. 15, in which the battleship Kirishima was sunk, the initiative in the Pacific War passed from the Japanese to the Americans.

Among those who sacrificed themselves for that pivotal victory, was Young, who posthumously received the Navy Cross for his valor during the desperate fighting in Ironbottom Sound.

Read the full article here