Gas Versus Inertia Shotguns

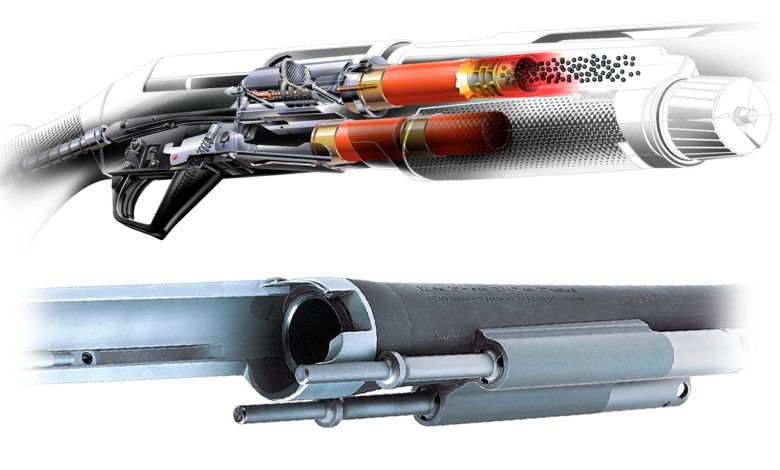

Whether inertia-operated (top) or gas-driven (bottom), the operating system of a semi-automatic shotgun will have pros and cons that must be considered before deciding which is best for your particular needs.

The godfather of semi-automatic shotguns is John M. Browning’s Auto-5, first produced in 1902. The design employed a “long-recoil action” that used the rearward recoil energy from the fired shell to push the bolt back (along with the barrel), thereby ejecting the spent hull and compressing a magazine-tube-mounted recoil spring to pull the bolt back into battery. The action was reasonably reliable and mitigated recoil via counteraction, but like nearly all mechanical systems, engineers later found that it wasn’t perfect and could be improved.

In 1958, Remington launched the Model 58 that was also described as having a recoil-operated action. But, instead of using the raw force of the shell’s kick to open the bolt, the 58 utilized what has become known as a “gas-action” system. In this system, when a shell is fired, expanding gas from the ignited powder drives the shot out of the barrel, and in doing so, a portion of the gas enters holes—or ports—in the barrel and is redirected toward the action to force the bolt backward. Because the amount of gas could be regulated by the size of the ports and other methods, engineers had more control in tuning the action to reliably cycle various loads. Also, harnessing some of that gas before it exited the muzzle did a great job of reducing recoil to the shooter’s shoulder.

In 1963, the Model 58 was improved by the Model 1100; since then, there have been scores of gas-action semi-automatics, some with slight differences and others with more significant ones. Over the years, gas actions were modified to self-regulate, so they could more reliably cycle the range of shell sizes and power without manual adjustment. Some featured springs mounted in the buttstock rather than in the fore-end to give the shotgun better “between the hands” balance, among many other innovations.

One recent and notable advancement (especially in terms of its simplicity) was Remington’s VersaMax, developed in 2010, which was rather similar to Benelli’s A.R.G.O. (Auto-Regulating Gas-Operated) system used in that company’s M4 Super 90. In a nutshell, the dual-piston VersaMax action relied on a series of seven ports that were regulated (either blocked or made available) by the length of the shell itself.

In 1968, Bruno Civolani invented what is now called the “inertia action,” which relies on a floating bolt and the principle of inertia that assures the gun moves around the bolt, rather than the bolt moving back on its own accord. Basically, when the gun fires, forces of recoil move the gun rearward as the heavy bolt tries to stay at rest. But, because the rotating bolt head is locked to the barrel extension, a heavy spring within the bolt is compressed. When the spring is compressed enough to overtake the recoil forces as they begin to wane, the spring uncoils, thereby pushing the bolt head forward, releasing the bolt head’s lock and causing the bolt to sling backward, thereby ejecting the shell. Although it sounds very complicated, it is astonishingly simple, with few moving parts—a big reason for its exceptional reliability.

Although the action didn’t become popular until the early 1990s with the release of Benelli’s game-changing Super Black Eagle shotgun, it was superior to most gas actions in several ways: First, because it didn’t send excess gasses and grime back into the action (instead ejecting out of the barrel), it was inherently reliable because it ran cleaner than gas-action semi-automatics that needed scrubbing after every few hundred rounds. Second, its bolt regulated itself, so a wide range of loads and shell sizes could be used. Third, because of the fewer number of parts, the guns can be made to be quite lightweight (Benelli’s 20-gauge guns weigh around 5 pounds). Since Benelli’s patent ran out (Benelli is now owned by Beretta), there are even more inertia guns from which to choose, including Browning’s new A5. Today, Americans have dozens of options in choosing gas-action or inertia-action shotguns.

So, which is better? That depends.

While it has been repeated that inertia guns are faster cycling, this is not necessarily true. Some gas-action guns are faster than some inertia-driven guns. What is true is that both actions are so fast that any tiny speed advantage is indistinguishable in actual use. In general—and with everything else being equal, including firearm weight—gas-action guns are perceived to recoil less than inertia-operated guns, mainly because the gas system tends to draw out the recoil-force curve over a longer timeframe so the kick is perceived to be softer. Although felt-recoil is dependent upon firearm weight, cartridge power and fit to the shooter’s body more than anything, if your primary concern is recoil mitigation, consider a quality gas-action gun. Browning’s Maxus 2, Beretta’s A400 Xplore and Remington’s VersaMax Competition (that also makes an excellent home-defense gun) are some of the lightest-recoiling 12-gauges ever made. While these guns aren’t like the Remington 1100s of old that required cleaning after every 200 rounds, they do need to be deeply cleaned with more regularity than inertia actions, perhaps every 1,000 rounds, depending on the severity of the conditions. Sand, salt water and frigid environments are not great for gas guns in general, because gas ports can clog.

If your primary concern is reliability in harsh environments or because you cannot clean the gun as regularly as you should, I’d recommend an inertia action, like Benelli’s M2. But, because gas actions have made big advancements in recent years—and the fact that I always keep my dedicated home-defense shotgun clean and lubed—I lean toward gas actions mainly because I’ve found that I inherently train and practice more with guns that recoil less, as they’re more pleasurable to shoot.

After a decent shotgun is chosen, regardless of action the most important factor is familiarity, and therefore proficiency, with it.

Read the full article here