America’s Secretive Technical Air Intelligence Unit in World War II

Beginning with the devastating air raids during the Attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States military was faced with a critical lack of information about the aircraft in use by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service. America’s prewar disdain for Japanese technology quickly changed to a frenetic quest up-to-date intelligence about the Rising Sun’s potent aviation.

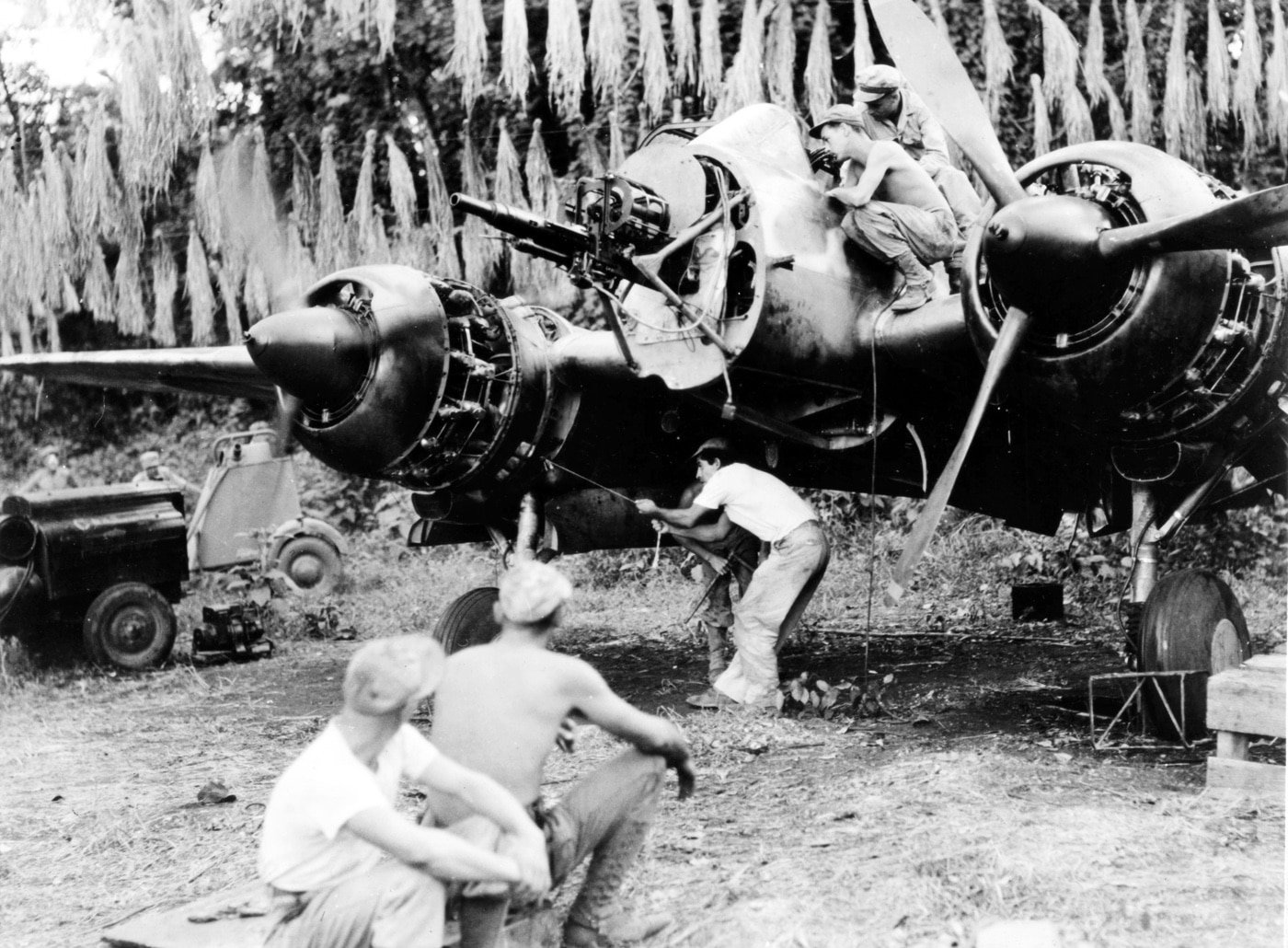

Initial finds were limited to bits and pieces of wrecked planes, salvaged from the jungle or shallow waters. An early intelligence victory was quickly lost when a nearly intact Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter was discovered near Port Moresby and inexperienced salvage crews roughly chopped off portions of the wings and fuselage to ship the plane back to Melbourne. To make matters worse, souvenir hunters stripped most of the instruments and data plates before the Zero even reached Australia.

It was quickly clear that an aviation technical intel organization was needed, along with a clearly defined process and regulations to identify, preserve, recover, study, and restore downed Japanese aircraft.

Birth of the TAIU: Technical Air Intelligence Unit

By November 1942 the cadre of the Technical Air Intelligence Unit (TAIU) was formed to search out Japanese aircraft, wherever they could be found, and to learn as much about their construction and capabilities as possible. The group was assembled with aircraft experts coming from the U.S. Army Air Forces, the United States Navy, the Royal Navy, the Royal Australian Air Force, and the Royal Australian Navy. This Allied unit was based near Brisbane, Australia.

Processes to evaluate Japanese aircraft wrecks and captures were standardized. This included a basic report form used to record specific details. Field personnel located and identified the aircraft (usually wrecks), and provided the initial evaluations before the materials were sent to an intelligence depot behind the lines for testing.

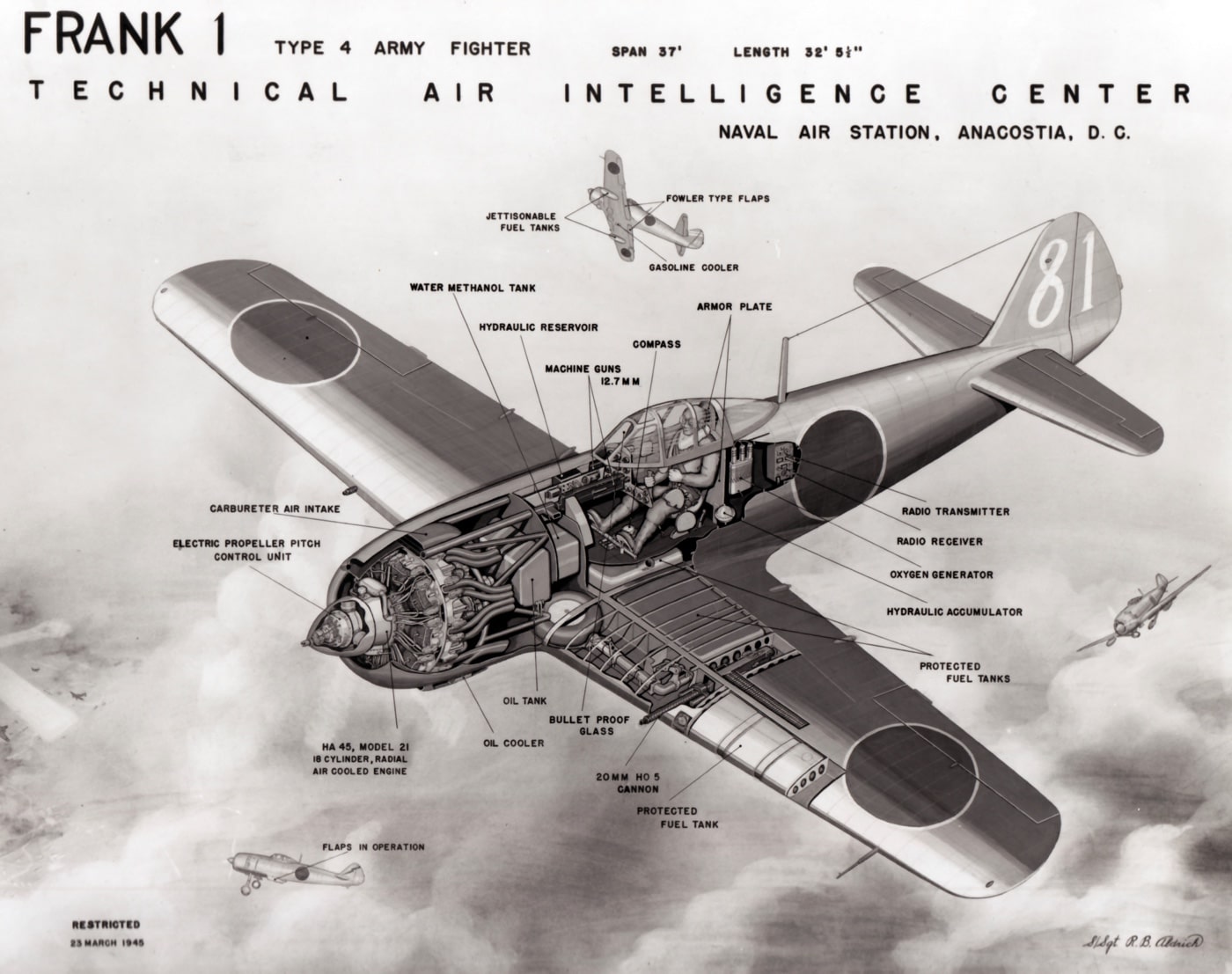

Tech Intel centers prepared identification documents, training materials, and whatever information could be determined regarding countermeasures to any specific aircraft type. The Americans were in overall command of the TAIU structure.

Dissecting Enemy Aircraft

The United States Army Air Forces intelligence service was focused around a small group of officers based at Wilbur Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio — part of the modern day Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. As the organization grew, so too did their ability to evaluate Axis aircraft and any captured documents related to them — captured technical documents were worth their weight in gold.

By 1943, a specialized Air Technical Intelligence (ATI) training course had been developed, and this provided an important background for U.S.A.A.F. and U.S. Navy TAIU officers. Air Technical Intelligence was not necessarily taken seriously by all Air Force commanders, and this led to the development of a centralized “captured air equipment center” in the United States of America.

Traditional in-fighting between the United States Army and U.S. Navy also held back some of the intelligence initiatives — it took two attempts to create a joint services tech intel center before this was finally resolved with the creation of the Technical Air Intelligence Center (TAIC) at NAS Anacostia (modern day Naval Support Facility Anacostia located near Washington, DC) during late 1943. The TAIC centralized the work of several test centers around the USA with the efforts of the TAIU teams operating around the globe.

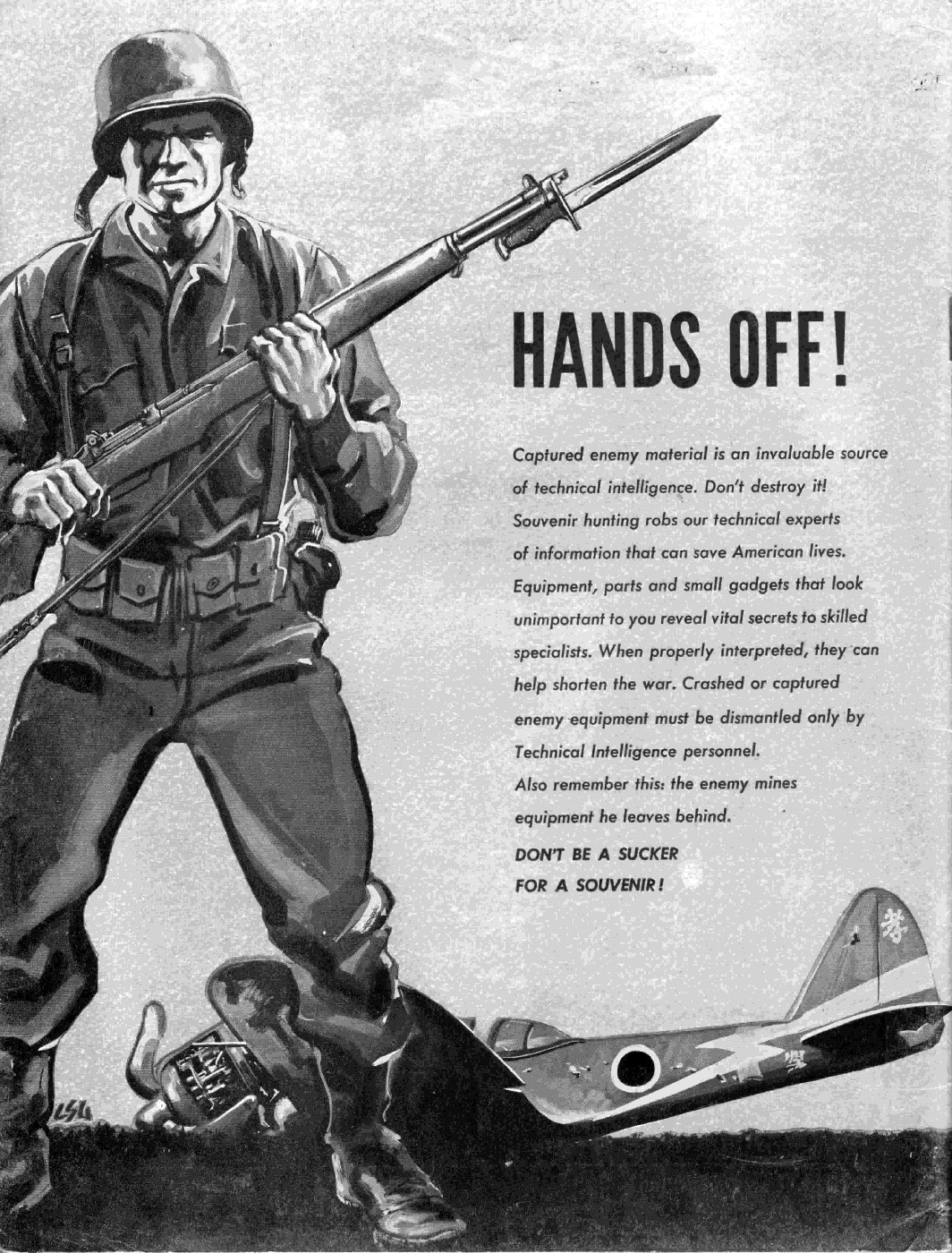

Despite strenuous efforts at educating the troops, TAIU operatives and the TAIC struggled throughout the war with the negative impact of souvenir hunters. U.S. troops never could keep their hands off important instruments, data plates, and weapons in captured Japanese aircraft. There was also ongoing competition between the different military branches of service and while it was considered “natural”, it was often damaging to the greater cause.

The far-flung and rugged nature of the Pacific theater was also a major challenge — crashed Japanese aircraft were often in barely accessible areas, and full recovery was often beyond TAIU capabilities. This inability to recover a full aircraft was particularly frustrating in the China-Burma-India theater, as the Japanese often debuted new aircraft in this area. On Pacific islands, TAIU teams were often in competition with the native tribes, as the locals valued the metal they could scrounge and melt down from the wrecks. There were no easy days.

Technical Victories, Technical Knockout

As American troops advanced across the Pacific, more and more Japanese aircraft were discovered, either in mostly complete or intact condition. After the details of the Mitsubishi Zero fighter had been revealed by early 1943, the TAIU began to pick up steam.

The invasion of Cape Gloucester yielded two intact examples of Japanese fighters that had previously eluded the TAIU: the Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien (code name “Tony”) and the Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu (code name “Nick”). The Nick was a twin-engine heavy fighter/bomber interceptor, and the version found in early 1944 provided valuable information on the type of aircraft the Boeing B-29 Superfortess bombers would face as they were soon to begin their offensive against the Japanese home islands.

The Ki-61 Tony was an important single-engine fighter (equipped with an inline engine, quite rare for a Japanese aircraft). The Ki-61 was carefully examined on site at Cape Gloucester, and deemed air-worthy with some maintenance. It was then disassembled and shipped to Australia for testing. Three flights were made at Eagle Farm Airport in Australia. Operating out of Hangar No. 7, a Royal Australian Air Force pilot was at the controls of the Ki-61 test flights.

It was intended to carry out performance tests against U.S. Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and British Supermarine Spitfire Mk VIII fighters. Further flights were cancelled after bearing metal was found in the oil filter. The “Tony” was then transferred to the TAIC Center at NAS Anacostia where it was repaired and made airworthy again.

The Battle of Saipan in mid-1944 yielded a tremendous haul of Japanese Naval aircraft, including several of the later variant of the Mitsubishi Zero, the A6M5 “Zeke 52” fighters, torpedo bombers, dive bombers, and heavy bombers. When American troops invaded the Philippines in late 1944 and recaptured Clark Air Base on Luzon, this yielded an intelligence bonanza, with most of the latest Japanese aircraft captured in working condition.

The TAIU teams continued working, and aircraft intelligence men were some of the first ashore on the Japanese home islands as the war ended, searching out the secrets of Japan’s latest and most advanced planes. Within a few months of the war’s end, most of the giant collection of Japanese aircraft, the intelligence finds that the TAIU had worked so hard to acquire, were being crushed and smelted in occupied Japan.

A Chance Encounter with a TAIU Veteran

I met Ray Peppler at a gun show in Pennsylvania during 2013. At that time, I was producing a series of photo study books on captured and wrecked Japanese aircraft in WWII, and during our conversation about those planes, I was surprised to learn that Ray had been part of the Technical Air Intelligence Unit, serving in the China-Burma-India theatre of operations. We exchanged addresses and I sent him a couple of books that I didn’t have with me at the show.

A few weeks later, I received a letter from him, and he was kind enough to provide some detail on his career and the mostly unknown operations of the secretive TAIU organization. I share it here with you, as it is one of the few personal records of TAIU field activities, particularly in the CBI:

“Got your book on the M1 Carbine and the one on Japanese aircraft.

Sorry I am late answering your letter. Most interesting that you know about our Technical Air Intelligence Unit, TAIU. Most people don’t know what it is at all.

I thought I should give you a little of my background. Excuse my writing, not so good at 95. Here goes with a little info:I graduated from Duke University with a BS in ME. This was the 2nd Duke Engineering class. Hard to get a job then. I finally got an inspectors job on the 3rd shift at Glenn L. Martin Co., Middle River, Maryland, in the experimental department. I worked on the B-26, PBM, and was also on the Martin Mars four-engine patrol aircraft through flight test. Then I decided to get in the Navy.

I went to Fort Schuyler (Long Island) and then to NATTC in Memphis, Tenn. I thought I would be assigned to Mars flight engineer school on Long Island but instead I was assigned to “TAIU” Anacostia.

I was only there a week before I was sent with two other officers to TAIU headquarters in Calcutta, India. They had three openings available: China, Burma and Calcutta. I got China.

I flew over the “Hump” to Kunming, China. I was there one day and was made a “Class B” Agent. I was authorized to carry $400,000 worth of Chinese money at all times. I had to carry it in a knapsack.

I carried a letter signed by Claire Chenault and endorsed by a top Chinese General stating that I was to be given any help and supplies that I requested. I was then told by an Air Force Colonel that I was to be a courier and take $1 million in cash (paper) into a remote airstrip with the money packed in cartons. A DC-3 pilot, co-pilot, and me flew into this tiny, rough strip.

There we met up with the person to receive the money along with my interpreter (Sammy Leung Yik Chong), a young Chinese man from a wealthy family in Rangoon. His family had all been killed by the Japs.

We made our way north to Nanping, China, where our TAIU HQ was located. When we arrived, there were five of us in total, Captain Jansky (27th AF) in charge. He was on his third tour. We arrived at a Methodist mission outside of Nanping. The lady missionary was still there. Nanping is 90 miles up the Min River from Fuchow.

Our main task was three-fold if we found a crashed aircraft:

- Using special tape (2 inches wide with black squares every two inches) we marked off the aircraft. I was issued a Kodak Medalist camera (the best). Took pictures at certain angles and distances, and got the film back to Anacostia, where they made recognition models and photos.

- We were issued complete sets of metric wrenches (Japs used metric). I had sockets, open-end, ratchet, from 1/8th to 3 inches. I had to take the crashed aircraft apart and get all of the name plates from the wreck. After the war had started, the US stopped serializing and putting the date of manufacture on all parts — but the Japs never did. TAIU had gotten a Frenchman with 25 years of experience out of the Jap aircraft industry. Back at Anacostia he would match up the photos of the name plate data and their corresponding production facility in Japan. These were increasingly hit by B-29s. Very secretive.

- We always checked the impact point of the guns. They did not fire parallel, so determining this our pilots could avoid this point.

Details of my assignment to TAIU:

I got two crashes:

- The first crash was about 350 miles due west of Nanping. It took over one month to get there. I had to hire Coolies at way stations about 30 miles apart. It took about 10 Coolies each carrying 80 pounds on yo-yo sticks to transport all my stuff. When I got there, it was obvious that the plane had been on fire in the air, but the crash put it out ok. Big pieces were laying around the area. Sammy put the word out that anybody bringing in parts (or paper) would be paid in cash. Thus, many people came. Best of all was the collection of paper. As it turned out, there had been three Generals with their families on board. All died. Many of the papers brought to me detailed the upcoming Jap battle plan. The Betty bomber they had been travelling in was quite old.

- The second crash was on an island, about twenty miles off the coast. A Jap fighter pilot on a training flight had run out of fuel and belly landed on the beach. The pilot was captured. The people on the island had never seen a white person before. My interpreter Sammy, who spoke five dialects, plus Mandarin, could not understand them at all.

At the war’s end, I did not have enough points to get of the service, and so I became a NAS Priority officer in Shanghai. Eventually went to NAS Mojave, California.

Ray Peppler

June 16, 2013

I did a bit of research and was able to find some documentation about the type of work that TAIU field operatives like Ray Peppler were expected to do. Clearly, their work was delicate and dangerous, and the tactical environment varied greatly. Even so, Mr. Peppler’s descriptions of his activities in China match up well with the instructions put forth in the 1944 “Handbook for Combat Air Intelligence Officers.”

Handbook for Combat Air Intelligence Officers Excerpt

TECHNICAL AIR INTELLIGENCE:

a. Technical Air Intelligence is derived from examination and analysis of captured, crashed or otherwise acquired articles of enemy equipment. Analysis of such materiel reveals the enemy’s technical progress and methods, his new and improved aircraft armament, weapons, ammunition and equipment, and betrays his shortages of critical materials or equipment, thus indicating his potential future production of aircraft, tanks, guns and other materiel.

b. While S-2 of group or squadron is not expected to usurp A-2’s responsibility for examining or analyzing captured enemy materiel, he is expected to train all personnel to guard captured or crashed enemy aircraft and air materiel, and to make certain that no one has access to such materiel prior to the arrival of qualified technical air intelligence officers. Particular care will be taken to protect the materiel against souvenir hunters.

c. The following are the chief sources of Technical Air Intelligence: (1) foreign technical press, (2) agents in enemy and neutral countries, (3) prisoners of war, (4) captured documents, (5) captured enemy air equipment.

Tiny Pieces of the Intelligence Puzzle

Technical Air Intelligence teams were faced with tremendous challenges — their opportunities to recover complete and operational Japanese aircraft were few, so they had to take their victories wherever they could find them and complete the aviation intelligence jigsaw puzzle one small piece at a time.

In that light, the following is a TAIU report on the Japanese Type 97 aircraft machine gun, an important weapon for Japanese Army and Navy air forces throughout the war.

TECHNICAL AIR INTELLIGENCE CENTER NAVAL AIR STATION ANACOSTIA, D.C.

EXAMINATION OF JAPANESE “BROWNING” MACHINE GUN

November 1944

A Japanese aircraft “Browning” .50 caliber machine gun (BMI #437 — CEE #2950) Serial #2349, manufactured in November 1942, was received from the Technical Air Intelligence Center, Naval Air Station, Anacostia, D.C. for metallurgical examination. The gun was captured at Lae, New Guinea, on September 16, 1943, complete and in good working order. It had been used for a nominal period on a Japanese fighter “Oscar”.

The weapon was copied from an early American model with minor modifications. Heat treatments were simpler than American practices, and flame hardening was used extensively. An interesting feature was chromium plating in the bore of the barrel.

The gun shows manufacturing methods similar to other Japanese guns examined and displayed good workmanship. Bearing parts possessed a good finish while a large number of exterior surfaces showed hand finishing. No brazed or stamped parts were used.

Delivering a Total Zero

Sometimes, air intelligence teams got lucky. Early in the war, the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 Model 21 was the dominant fighter of the Pacific theatre. Allied forces knew little about its design, but they knew enough to realize they had nothing of equal ability. Then suddenly, their luck changed.

On June 4, 1942, Japanese aircraft struck the American base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands. One of these planes was a Zero fighter piloted by 19-year-old Tadayoshi Koga. During a strafing run on American positions, Koga’s Zero was struck by ground fire that cut his oil line. Noticing this, Koga headed for Akutan Island, a pre-designated landing field for damaged Japanese aircraft.

Koga landed on what appeared to be a grassy field — however it was a grassy bog. The Zero’s landing gear snagged and the fighter flipped, and came to rest upside down with minimal damage. Koga died in the crash as his neck was snapped, but his squadron-mates had no idea for all they saw was an intact Zero, albeit on its back. The fortunes of war prevented the Japanese from recovering or destroying the aircraft.

On July 10th, a US Navy scout plane spotted Koga’s Zero on Akutan. It took three recovery attempts, but U.S. Technical Air Intelligence teams finally recovered the aircraft, and within weeks the Zero had surrendered the secrets of its design, particularly its faults.

Final Thoughts

The work of the Technical Air Intelligence Unit (TAIU) underscored the pivotal role of technical innovation and intelligence in modern warfare. Despite the challenges of terrain, resource limitations, and inter-service rivalries, the TAIU provided critical insights into Japanese aviation technology that shaped Allied strategy and tactics.

Their painstaking efforts to recover and analyze enemy aircraft not only leveled the playing field in the skies but also demonstrated the value of collaboration across nations and services in overcoming a technologically advanced adversary. As a testament to their ingenuity, the contributions of these unsung heroes resonate in the broader story of Allied victory in World War II.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here