Battle of Cape Gloucester: Misery Manifest

Hurricanes can be hell. Typhoons are typically terrible. But when it comes to all-around, rain-soaked, human misery, the tropical monsoon tops the charts. This is especially true if you’re out in it with nothing but a steel helmet and the shirt on your back when relentless, solid sheets of rain leave you sucking water rather than air. Add to your misery a fanatical enemy, plus man-eating mangrove swamps and a jungle so dense it defies human incursion, and you’ve got some notion of what the 1st Marine Division faced at Cape Gloucester during World War II.

As Christmas approached in 1943, the division was supposedly in a rest and refit status in Australia following the brutal six-month campaign at Guadalcanal that came to an end for the Marines in January. Survivors of that first big American offensive against the Japanese in the Pacific needed the break. They were exhausted, emaciated, under-nourished and malaria-ridden after their stand in the Solomons.

Regardless, Division Commander Major General William Rupertus pushed his weary veterans hard in a relentless training schedule. He had no choice as floods of green replacements were reporting for duty to flesh out his line infantry outfits, including the 1st, 5th and 7th Marines plus 11th Marines artillery batteries. Lessons learned at Guadalcanal were being incorporated into division supporting elements such as tanks, amphibian tractors, engineers, naval gunfire, air support and logistics. It was a huge task, and division leaders prayed for sufficient time to get everything done before another big mission came their way.

Dialing In the Target

No good deed goes unpunished in the Marine Corps, so no one was overly surprised when the 1st Marine Division, under General MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area command while they were in Australia, was alerted to take part in his scheme to bull his way closer to a promised return to the Philippines. MacArthur considered the division his Marines and planned to use them in an assault on the northwest shore of New Britain island at a spot called Cape Gloucester. The landings were scheduled for 26 December. Merry Christmas.

While the division loaded up aboard an amphibious task force at Melbourne, General Rupertus and his senior leaders reviewed the bidding at that stage of the war in the Pacific. Many were unhappy with MacArthur’s plan and had argued vociferously against parts of it. A wild-eyed parochial scheme to drop the Army’s 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment inland on New Britain in support of the advancing Marines was nixed as overly costly and nearly impossible given the thick jungle that covered most of the island.

Another typically grandiose element of MacArthur’s strategy was to include the pivotal Japanese air and sea base at Rabaul as an objective for the operation, now code-named Dexterity. Even members of his own staff sided with the Marines objecting to that as a bridge too far. Since the Japanese had landed at Rabaul on the northeast point of New Britain in 1942, they had developed a sprawling base with port facilities and airfields manned by a formidable number of defenders. Reluctantly, MacArthur agreed that Rabaul should be bypassed and pummeled continuously by air strikes rather than subject to a ground attack. The focus of Operation Dexterity was narrowed to western New Britain and the seizure of the all-important Japanese airstrip at Cape Gloucester. Get that done, and MacArthur’s flanks would be safe from enemy airstrikes as he fought on New Guinea and drove toward the Philippines.

By this time in the war, pre-invasion landing preparations had become SOP. On 26 December, U.S. and Australian cruisers and destroyers steaming along the Bismarck Sea pounded Japanese positions on New Britain. Spotters had a difficult time seeing any effect onshore because of the thick jungle reaching right down onto the proposed landing beaches. It was the first clue to the difficulties the Marines would encounter once ashore at Cape Gloucester. Another clue was a pelting rain that started just after dawn and didn’t let up much for the entire run of the operation. The winter monsoons had arrived at Cape Gloucester.

Despite deteriorating weather, the U.S. Army Air Corps managed to get flights of B-24s and B-25s into action. The only indicator that the strikes had any effect was a mushroom cloud rising skyward, indicating an enemy fuel dump may have been hit. Hoping for the best, the order to land came at 0745 on the day after Christmas, and the 7th Marines headed for the shoreline of Cape Gloucester.

Meeting the Enemy

They encountered no enemy reaction as they landed on Yellow Beach 1 and 2, but the jungle was just as formidable an obstacle as Japanese defenders. Right off the landing craft, the Marines had to break out machetes and start hacking a path inland. A half-hour later, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines (3/1) landed on the 7th Marines right flank, followed shortly by 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines (2/1). More machetes were added to the push inland, but still not much reaction from Japanese defenders.

Some of that was due to the sparse numbers of defenders around Cape Gloucester. The Japanese had committed a scatter-shot unit to the defense of the central and western parts of New Britain. They were nearly as hampered by weather and terrain as the assaulting Americans. Japanese General Hitoshi Imamura had his 8th Army command at Rabaul and he was only remotely in touch with his subordinate commands. Much of his fighting strength was tied up defending in New Guinea or the northern Solomons.

Imamura had just a cobbled together 65th Brigade to cover all of New Britain. Much of that scattered command was support troops rather than battle-tested infantry, and Major General Iwao Matsuda commanding the brigade was a transportation officer with little infantry experience. What was facing the Marines at Cape Gloucester was a Japanese force of a little more than 12,000 soldiers, many of them not trained infantrymen, and most of them without prior combat experience.

That didn’t do much to ease the burden on Marines dealing with some of the most inhospitable terrain Americans had ever encountered. An official report on conditions in and around Cape Gloucester was startling.

Decay lies everywhere just under the exotic lushness, emitting an indescribable odor unforgettable to anyone who has lived it. Insect life flourishes prodigiously: disease-bearing mosquitoes and ticks, spiders the size of dinner plates, wasps three inches long, scorpions, centipedes.

Through that mess and more, the Marines hacked their way slowly inland, aiming to capture the vital airstrip and what few pieces of high and dry ground they could identify.

Japanese defenders were hindered by the same horrible terrain and pelting rain but they sucked it up and deployed units of their 53rd Infantry — about 4,000 men — to defensive positions around that vital airstrip and adjacent to Borgen Bay which curved around to the south of the initial landing sites. A second Japanese combat command, the 141st Infantry was scattered in strong points to the south and east, making mutual support difficult for the defenders.

That put the Japanese 53rd Infantry straddling the Marines’ axis of advance. That advance, slow and steady, actually split the Japanese defending units in half and cut them off from each other. Any direct combat that occurred was usually an American outfit stumbling around in the rain and running into a Japanese outfit with seriously reduced visibility. And things just got worse in a place that the Marines had started to call The Green Inferno.

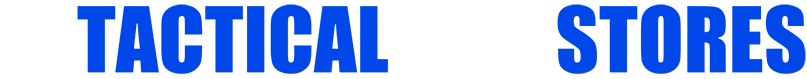

Battling the Elements

The 7th Marines managed to advance inland to an open stretch called the “damp flats” which was pitted with muddy sinkholes. Riflemen trying to cross the open terrain often sunk up to their hips in mud and had to be rescued by two or three buddies heaving them out of muck that had the consistency of quicksand. Casualties from sprains or broken bones began to mount. And all along the advance, which involved scattered firefights, Marines were felled by rotting trees when rain-saturated roots gave way. The first American casualty on Cape Gloucester was a Marine killed by a falling tree.

The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines finally reached a high-ground redoubt marked on maps as Target Hill. To do it, they had to overrun and destroy a Japanese 75mm gun that fortunately could not be traversed in the muddy terrain. By the end of a very miserable week of fighting against the Japanese as well as the weather and terrain, American forces on Cape Gloucester held a shaky perimeter of captured Japanese positions about 900 yards inland of the landing sites. They dug in to hold in marshy ground against repeated enemy counterattacks.

Meanwhile, the 1st Marines were making their way toward the vital Japanese airfield. On point was a company of 3/1 which ran into stiff enemy resistance from bunkers and strongpoints blocking approaches to the airfield. That’s when infantrymen found out that the weather and soupy terrain had some negative effects on their organic supporting arms. Bazooka and 60mm mortar rounds simply buried themselves in the ooze without exploding. Soupy mud and rain-drenched earth didn’t provide sufficient resistance to trigger point-detonating fuses. Flamethrower units called up from the landing areas didn’t help. Gunners couldn’t get the weapons to ignite in the constant downpour.

To counter these problems, artillery units from the 11th Marines came ashore and drove inland to support the infantry with their 105mm howitzers firing timed fuses that would detonate above ground. That was the plan, but the artillerymen promptly ran into problems of their own. The guns got bogged down before they could register to shoot. It took a gaggle of AMTRACs and bulldozers to move the cannons forward into firing positions on semi-dry ground. Tanks began to roll in from the landing ships and the Marine Shermans proved to be a godsend as they could traverse much muddy terrain that was impassable for everything else with wheels or tracks.

Early in the operation the weather gave both sides a break long enough to launch a few miserly airstrikes. Army Air Corps B-25 bombers headed for New Britain on a bombing run in support of the Marines. The Japanese had similar plans and sent their own bombers and fighters from Rabaul to support defenders on Cape Gloucester. At some point over the landing sites, the two air forces tangled. Nervous Navy gunners aboard ships in the beachhead area, blazed away at the Japanese aviators with an intense curtain of AA fire. Unfortunately, the gunners aboard LSTs out in the bay got confused in the melee and shot down several American planes. The Japanese were on the losing end of the air battle with most of the planes they sent shot down, but they did some damage. They managed to seriously damage a U.S. destroyer that later sank.

American Marines at Cape Gloucester continued to struggle forward while Japanese defenders put up stubborn resistance. Incessant rains lasted for hours every day and it would continue that way nearly every day the 1st Marine Division spent at Cape Gloucester. Hurricane-force winds blew in from offshore, bringing thunderstorms and lightning. Troops were temporarily blinded by lightning flashes and the peal of thunder made it hard to tell storm noise from enemy fire.

It was miserable for both sides. A few excerpts from a 1st Marine Division situation report provide some insight:

Ground has become a sea of mud. Water backed up in the swamps has made terrain impassable except for amphibian tractors. Streams that emptied into the sea have become raging torrents all along the route of advance toward the airfield. Troops soaked to the skin, and their clothes never dried out during the entire operation.

Typically, the Japanese defenders of the 53rd Infantry decided it was a perfect time for an all-out banzai attack. The fighting around positions held by 2/7 was surreal at times, with rain falling in sheets with thunder and lightning flashes strobing the battlefield. Soaked weapons caked with mud misfired. Much of the fighting involved fists and bayonets before the Japanese were driven off, leaving 200 dead behind them.

The Crown Jewel

General Rupertus was not a patient man. His staff had convinced him to wait for the 5th Marines being held in reserve to come ashore and augment his two regiments struggling forward at Cape Gloucester, but he wanted that airfield and congratulations from Gen. MacArthur.

Rupertus pushed two battalions of the 1st Marines into the advance reinforced by all the tanks he could muster. They had some success initially at a place they called Hell’s Point, but hit stiff resistance from a dozen or so massive bunkers. The Japanese 75mm cannon in those bunkers proved ineffective against the Shermans backed by riflemen. The Marines killed some 300 defenders in the fight. With that defensive line penetrated, Rupertus could mass for a concerted move on the enemy airfield. He sent dozers and AMTRACs forward to clear a route, and establish supply points and medical facilities he’d need when the 5th Marines landed to back his push.

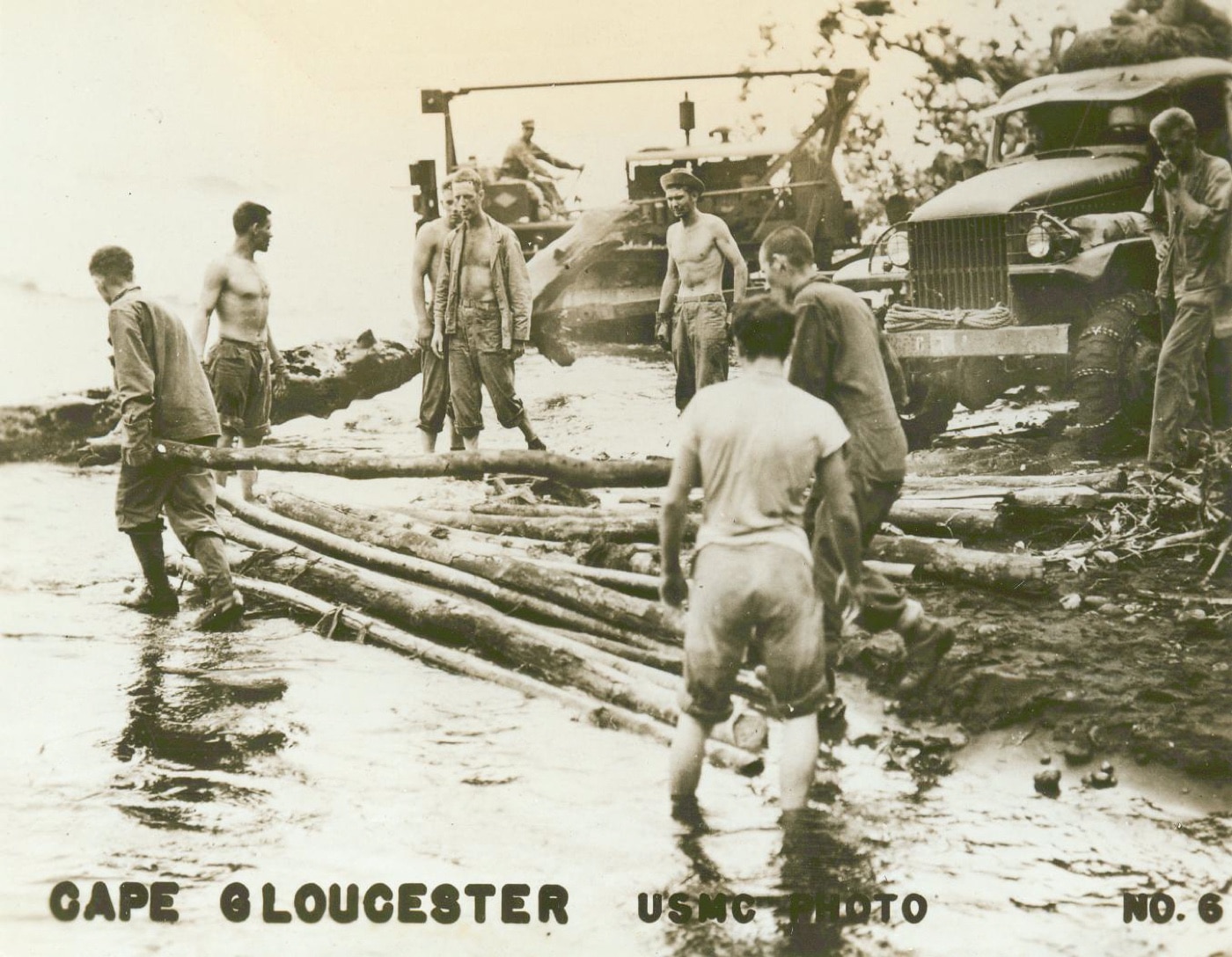

That’s when the 1st Marine Division caught a valuable break. A patrol ran onto a lone Japanese soldier buried up to his neck in thick mud. This survivor turned into a goldmine of valuable intelligence. Under questioning, the Japanese soldier told his captors about plans for a large contingent of the 141st Infantry to counterattack and reinforce along the axis of advance to the airfield. When Rupertus got wind of this, he decided to advance the schedule and brought the 5th Marines ashore without further delay.

As fresh troops landed, Rupertus ordered the 1st Marines to push hard toward the airfield while the 5th Marines deployed on their left flank to stop any enemy reinforcing from that direction. As it turned out, the starch had been washed out of the Japanese forces at Cape Gloucester who were just as miserable as the Marines they were facing. What defense they put up against the final push to capture the airfield was lackluster, at best.

Backed by tanks and hub-to-hub artillery batteries, the Marines pushed through a tangled rainforest. And as they advanced, suddenly, the incessant rain stopped for a while, giving way to bright sunshine. That breathed new life into the weary, soaked Marines who advanced with vigor behind tanks and AMTRACs.

Behind this unexpected surge of good weather, the 1st Marines made it to the airfield and drove off the remaining defenders. When the 5th Marines arrived shortly thereafter, the situation was well in hand. General Rupertus, on New Year’s Eve, wired MacArthur letting him know that the airbase was in Marine hands and one of the primary objectives of Operation Dexterity had been achieved.

Desperate Defenders

Unfortunately for the Marines on New Britain Island, the fighting would continue against Japanese forces for another two months. As usual in operations in the Pacific, the Japanese refused to concede defeat. 1st Marine Division units around Cape Gloucester fought off several suicidal assaults as they expanded their foothold and fought against more miserable weather.

Typical last-gasp efforts by Japanese troops included desperate attempts to shove Marines off of tactical strongpoints at Target Hill and Suicide Creek. In the first of those, elements of the 141st Infantry ran up against defenders under cover of their own artillery and mortar fire. Marines resisted furiously in a fight that lasted two days before attackers were driven off, leaving some 200 dead behind them.

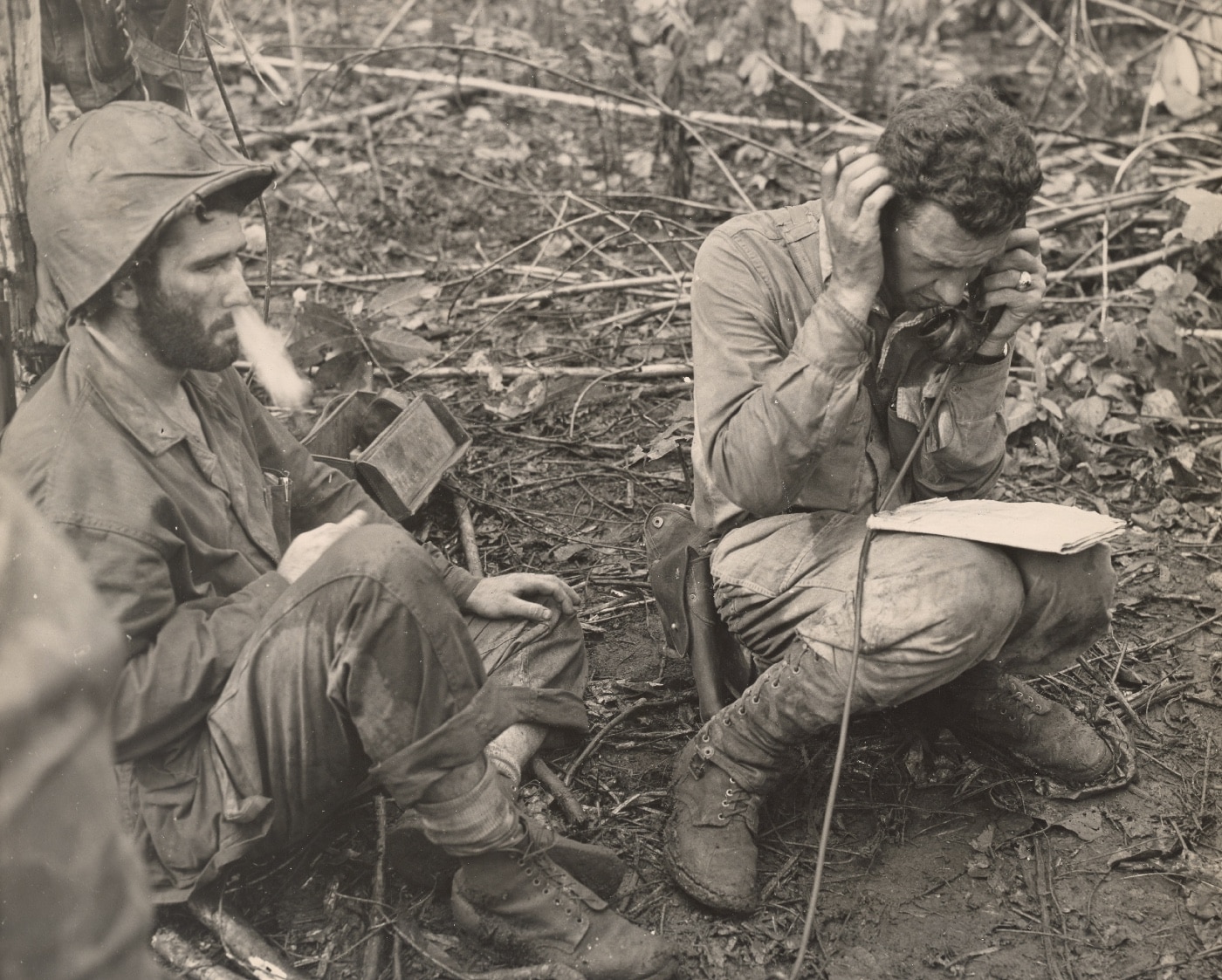

Fighting at Suicide Creek on 2 January was less straightforward. Advancing Marines ran into a deeply entrenched Japanese outfit guarding positions near a rain-swollen waterway. Marine Engineers were called forward with bulldozers and labored under intense incoming fire to build a log road across a swamp that flanked the creek. They got it done and paved a way for tanks to come forward, cross the raging waters and eliminate the enemy. However, the action cost four Marines killed and another 200 wounded to secure a stinking creek that cut through the fetid jungle of Cape Gloucester.

There were other brutal fights over the next couple of weeks involving action at most of the Marine-controlled high ground, including Target Hill, Aogiri Ridge and Hill 660. Most of it was similar in nature. The Japanese attacked over sodden ground against Marines who defended from waterlogged fighting holes or the other way around.

When crucial positions flanking Borgen Bay were declared secure on 16 January 1944, Japanese resistance essentially collapsed and the battle was reduced to scattered fighting with tenacious survivors. Those fights ranged from small meeting engagements to full-blown, battalion-level attacks, but it was clear that the Japanese in the Cape Gloucester area of New Britain had shot their bolt. Japanese General Matsuda issued orders for his remaining 1,100 troops to fall back toward Rabaul. They were chased by long-range Marine artillery that had come ashore during the preceding days as well as Marines sent by Rupertus to try and cut off their retreat.

The Right Strategy?

Controversy plagued critiques of the Cape Gloucester operation, with some critics claiming the reward fell well short of the cost to capture a lot of swampy ground and one Japanese airfield.

Despite the horrid conditions they faced, Marine viewed it from a more positive angle. Operation Dexterity taught them some valuable lessons that paid dividends later in the Pacific war. It was a rocky start due to appalling weather conditions at New Britain island, but subsequent operations proved that tanks could be valuable multipliers in jungle fighting. They also emphasized the importance of Engineers and Shore Party support, and demonstrated effective ways to use those assets in adverse weather and terrain conditions.

To learn those lessons and gain a victory at Cape Gloucester, 310 Marines were killed and another 1,083 were wounded. Records of the time don’t adequately reflect the number of men put out of action by tropical disease or related illnesses. And there were a lot of those after action on New Britain. For the rain-drenched riflemen who survived, the major lesson was that the jungle and the weather can be as deadly an enemy as the Japanese.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here