The WWI aviators who gave their lives to help the ‘Lost Battalion’

By the time the First Army of the American Expeditionary Forces launched its first major offensive at St. Mihiel on Sept. 12, 1918, the world had been at war for nearly four years. With the success of St. Mihiel, Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the AEF, set his sights on an even more ambitious advance: The Argonne Forest.

It was here, however, that the American “Doughboys” encountered their first serious opposition — the German Fifth Army.

During the grueling six-week campaign that ensued, the AEF was provided a degree of innovative air support that included the Army’s first home-manufactured airplane — albeit a license-built British design, the De Havilland DH-4. Reaching the front were only 198 of the aircraft, which had to be supplemented in American squadrons by French-built Salmson 2A2s.

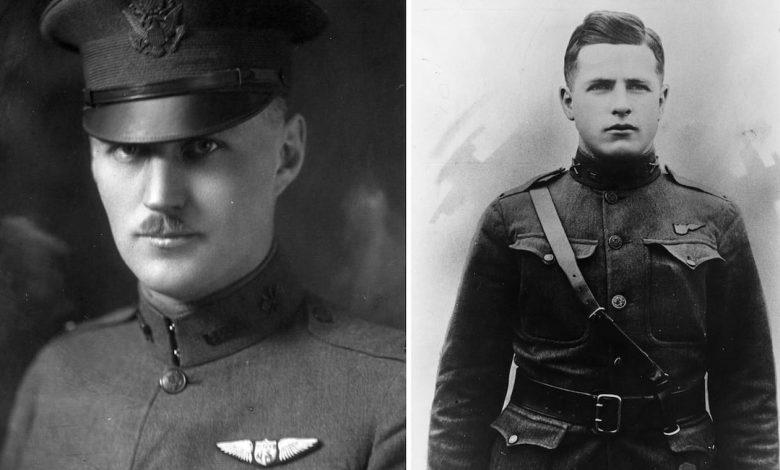

Only four airmen were awarded the Medal of Honor during the First World War, with two aviators, 1st Lt. Harold E. Goettler and 2nd Lt. Erwin R. Bleckley, earning the honor during one of the most dramatic battles fought within the Argonne Campaign: that involving the “Lost Battalion.”

Harold Ernest Goettler was born in Chicago, Illinois on July 21, 1890. After the U.S. declared war in April 1917, he joined the Signal Enlisted Reserve Corps in July, but transferred in October to the USAS for flight training at the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois.

He graduated in January 1918 and in February he received his second lieutenant’s commission. After further training in the 28th Aero Squadron, he transferred in August to the 50th Aero Squadron, based at Amanty aerodrome, France.

Erwin Russell Bleckley was born in Wichita, Kansas on Dec. 30, 1894, and was working as a teller in the Fourth National Bank of Wichita when war broke out. On June 6, 1917 he enlisted in Battery F, 1st Field Artillery, Kansas National Guard and obtained his second lieutenant’s commission on July 5. This unit was activated and redesignated the 130th Field Artillery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma and attached to the 35th Division.

Having transferred to the 50th Aero Squadron on Aug. 14, 1918, Bleckley began flying missions as an observer pilot with Lt. Goettler at the outset of the St. Mihiel Offensive. It did not take long for the pair to be listed among the squadron’s most dedicated and reliable duos.

The Argonne offensive encountered difficulties from the start, but an exceptional crisis began on Oct. 3, when 554 soldiers, all from the 77th Infantry Division, found themselves cut off by a ravine alongside the Charlevaux road.

That mixed component of troops, under the overall command of Maj. Charles W. Whittlesey, became known as the “Lost Battalion,” despite the 77th not exactly being a battalion nor particularly lost.

Its plight, however, was quite real.

Surrounded by elements of the German 76th Reserve Division, the Doughboys were pinned down by adversaries they actually outnumbered, but who were intimately familiar with the terrain. The Germans controlled the high ground, with machine guns that turned every inch of the ravine into a killing zone.

On Oct. 4, two attempts by the 77th Division to break through to the trapped men were repulsed, resulting in more than 200 casualties. Meanwhile, the cut-off units, commanded by Whittlesey, lay isolated, out of communication with the AEF and were soon suffering from dwindling ammunition, food and water.

The following day, Capt. Daniel P. Morse, commander of the 50th Aero Squadron, got a telephone request from the 77th Division to airdrop supplies to Whittlesey’s command. Boxes of ammunition, food and medical supplies were rushed to the aerodrome wrapped in blankets, straw, rags and cardboard in an attempt to prevent items from breaking when they hit the ground.

Meanwhile, a DH-4 tried unsuccessfully to pinpoint the Americans’ location. When Lieutenants Floyd M. Pickrell and Alfred C. George tried again the next morning, they came under intense ground fire, but as they flew over the ravine they spotted khaki-dressed soldiers waving from their dugouts. George hastily threw out the supply bundles, while Pickrell marked the location on his map.

Later that morning, as a French division tried to link up with the “Lost Battalion,” only to be pushed back by German counterattacks, Morse ran an aerial shuttle service in an attempt to supply the besieged troops.

It was no easy task. Whittlesey’s men had laid out white panels for the aircraft, but he ordered them taken in because they drew enemy fire. The Germans also laid out marking panels, trying to trick the Americans into dropping the supplies to them — which happened all too often, as packages fell outside of the 1,800-square-yard area in which the “Lost Battalion” was pinned down.

Meanwhile, enemy ground fire intensified with each sortie. Two DH-4s were downed behind German lines on Oct. 6, but their crewmen, Lieutenants George R. Phillips, Mitchell H. Brown, Allen Tracy Bird and William A. Bolt, managed to make their way back to the Allied side.

First Lt. Maurice E. Graham landed with his observer, 2nd Lt. James E. McCurdy, seriously wounded in the neck. After several flights, DH-4 No. 2, flown by 1st Lt. Goettler and 2nd Lt. Bleckley, had to be retired for repairs.

With time for one more sortie before darkness fell, Goettler and Bleckley took to the skies, dropping several bundles into the Americans’ approximate area.

As Goettler came back around at almost treetop height to drop his last few parcels, he and Bleckley were both struck by ground fire, but he managed to reach Allied lines before crashing. There, French soldiers found Goettler dead in the cockpit. Bleckley died moments later, but not before he passed on information to give the Allied artillery more accurate coordinates on the American and German locations.

At dawn on Oct. 7, a reinforced 77th Division finally drove the Germans back and re-established contact with the “Lost Battalion” that evening. By then, only 194 of Maj. Whittlesey’s command were still standing.

In the first such operation to be performed by the AEF, the 50th Aero Squadron had airdropped more than 1,200 pounds of supplies in 18 hours. However, only a fraction of that reached its intended recipients, and the effort cost the squadron two men killed and one wounded.

The two airmen who sacrificed their lives in support of their comrades on the ground, Goettler and Bleckley, were both posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, with the both aviators’ citations reading that the men “showed the highest possible contempt of personal danger, devotion to duty, courage and valor.”

Read the full article here