Fitting the Shotgun

One aspect of shotgunning that is often misunderstood is shotgun fit and how it relates to speed, accuracy and recoil mitigation. Although perfect fit is not absolutely required for precise pattern placement because shotgunners can employ the use of conventional sights or optics, a well-fitting shotgun that is mastered can facilitate shooting that is quicker, superior for moving targets and easier on the body.

However, shotgun fit is a complicated issue because people, guns and preferred sighting systems differ. While I don’t have the space to go into the proper shotgun fit for each, all shotgunners are best served by taking the time to ensure their gun fits.

For the sake of brevity, I’ll discuss fit for traditionally stocked shotguns using a single-front-bead sight. This setup facilitates instinctive shooting, but it requires the head and eye to be set in exactly the same orientation firmly on the stock from shot-to-shot, because the eye itself serves as the rear sight. Therefore, if shooting form is not to falter, the rear sight’s position—i.e., the eye—can only be adjusted by tailoring the gun to the shooter. In this way, point-of-impact (POI) compared to the shooter’s point-of-aim (POA) can be altered so the gun shoots where the shooter looks. What follows is how to know if your shotgun fits.

If you are new to shotgunning, you’re best served to learn proper shotgun mount, stance and body positioning before making any lasting gun adjustments. Also, try to erase rifle shooting from your muscle memory of what “feels right;” correct rifle fit is quite a bit different from that of a shotgun.

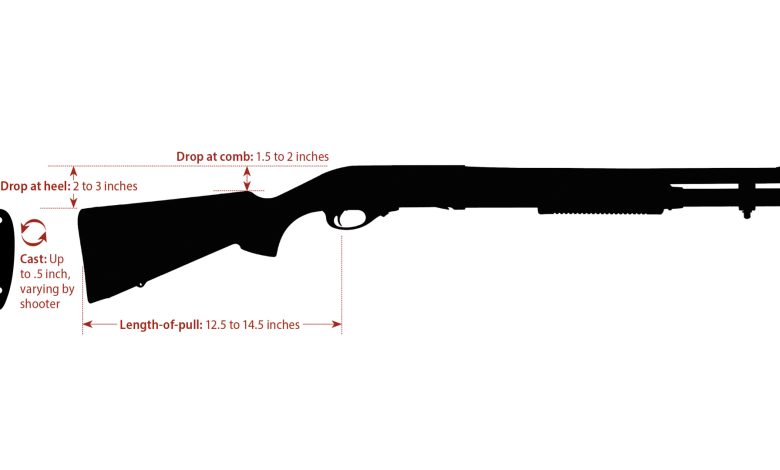

First, check your shotgun’s length-of-pull (LOP): the distance from the trigger to the middle of the buttpad. Most shooters fall into the 12.5- to 14.5-inch range. Too long, and the stock could snag on your clothing during the mount and/or make it tough to work the gun’s controls. Too short, and recoil is exacerbated. One simple test is to place the shotgun in the crook of the elbow formed by the biceps and forearm. If the last joint of the trigger finger lands on the trigger naturally, the stock’s length fits. If you can’t reach the trigger, it’s too long. Adjustments are relatively simple at home via your shotgun’s shim kit, or by having the stock cut down or lengthened by a gunsmith or your own handiwork. Once LOP is correct, move to the next step.

Although perfect fit is not absolutely required for precise pattern placement because shotgunners can employ the use of conventional sights or optics, a well-fitting shotgun that is mastered can facilitate shooting that is quicker, superior for moving targets and easier on the body.

With your eyes closed and the gun unloaded, mount and shoulder the shotgun naturally, as you would if you were about to actually shoot it. Make sure the buttpad is planted snugly in your shoulder pocket and your cheek is pressed firmly on the stock in a head-forward manner with your eyes level. (Pro Tip: To mount, bring the gun up to your cheek rather than lowering your cheek to the gun. Doing the latter increases the chance of contorting your body to fit the gun.) Then, with the gun mounted, open your eyes. If you shoot right-handed, your right eye should be looking perfectly along (parallel to) the sighting plane of the barrel; if you are looking down upon it at angle or under it, you’ll need to make adjustments to the gun. If you are unsure, have an expert shotgunner look on as you perform these tests.

Next, choose a target 20 yards away. While focusing on the target and ignoring the bead, mount the gun as if you were going to shoot. As soon as it is mounted, note the relationship between your eye, the front bead and the target. All should be aligned perfectly. If you must move your head to align them, you’ll need to make adjustments.

Finally, go to a range and place a large, blank, paper target with a set aiming point 20 yards away. Without looking at the shotgun during the mount or using the bead to consciously aim, mount the gun, point at the bullseye and pull the trigger. Do this multiple times. If you see a trend develop—such as the shotgun’s pattern consistently printing above, below or to the left or the right of the aiming point—you likely have a shotgun-fit issue that warrants stock adjustment.

Drop, specifically drop at comb, is the measurement of the sighting plane atop the barrel compared to the buttstock’s comb height. The more drop the gun has, the lower the eye can be placed on the stock in relation to the sighting plane. A “high comb” should be used for optics, so a proper cheek weld can be attained while looking through an optic well above the gun’s barrel. Drop is critical in terms of POA/POI for traditional shotgun shooters; if the eye is too high over the sighting plane and the front bead is placed on the target, your shots will go high, and vice versa. While shooters can become accustomed to guns that shoot high or low by subconsciously adjusting their POA to match the gun’s POI, if you are used to a gun that fits and then move to a gun that doesn’t fit, you’ll find that you’ll miss targets even when you think you should be hitting them.

Cast-on/Cast-off is the amount of lateral bend the stock has built into it to account for the body’s natural curvature, so that the eye is aligned down the middle sighting plane. For right-handed shooters, modern stocks often come with a small amount of cast-on. Lefties will benefit from cast-off. If you find your shotgun is patterning to the right or left of the target despite proper gun mount, consider adjusting the stock’s cast.

The good news is that many new shotguns come with a shim kit that enables many of these adjustments. If you take advantage of it, you’ll find that a well-fitting shotgun is one that is faster, more accurate and has less felt recoil. In essence, it’s one that’s easier to master.

Read the full article here