Handley Page Halifax: England’s “Other” Heavy Bomber

The Handley Page Halifax never attained the same level of fame as the Avro Lancaster, yet it was still produced in significant numbers and made a nearly equal contribution to the Allied victory in the Second World War. As one of the three four-engine bombers to see service with the Royal Air Force (RAF), along with the Avro Lancaster and the Short Stirling, the Halifax is remembered primarily for carrying out the night-time bombing offensive against Nazi Germany.

Yet, there is more to the story.

Whereas the Lancaster was noted for being able to carry ever-increasing bomb loads without degradation of its performance or handling capabilities, the Handley Page Halifax proved to be adaptable and served in a multitude of roles, including air ambulance, freighter, glider tug, personnel transport and maritime reconnaissance aircraft.

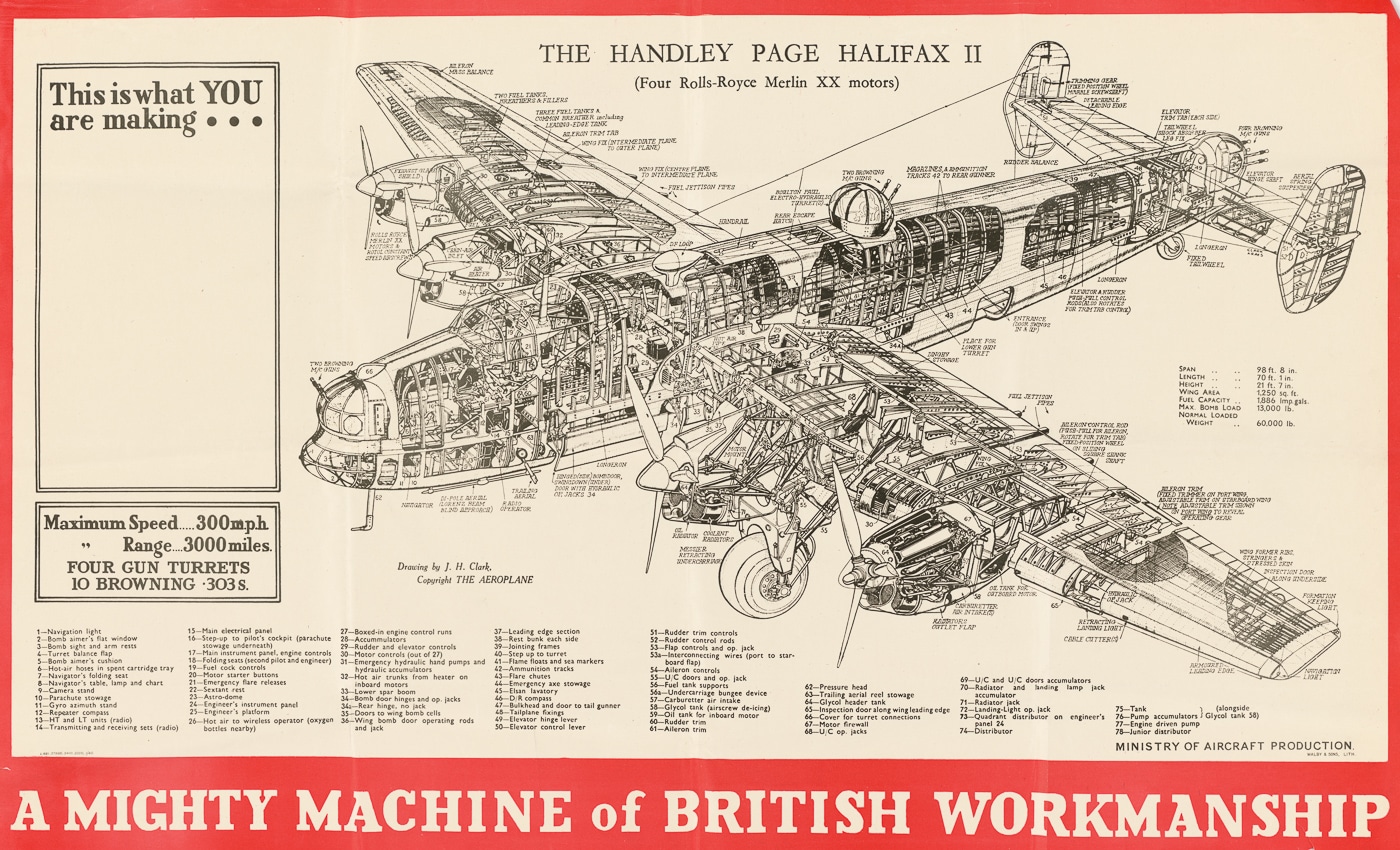

Beyond bombing German cities, the Halifax was employed in a variety of missions due to its formidable striking power. It took part in anti-submarine patrols and even para-dropped Allied agents into occupied Europe.

Production actually continued until 1946, with a total of 6,176 Halifax aircraft produced. However, just three survive (largely) intact today.

Began as a Twin-Engine Bomber

The origins and development of the Handley Page Halifax aren’t especially dissimilar to those of the Avro Lancaster, as both aircraft were born out of the UK’s Air Ministry’s call for a twin-engine bomber in the mid-1930s. At the time, there wasn’t seen to be a need for a four-engine bomber, and Handley Page submitted a design for the proposed H.P.55.

It was rejected in favor of the Vickers Wellington, and the Avro 679, which became the Manchester, the bomber from which the Lancaster evolved.

Yet, even as the British were focused on twin-engine bombers, the United States, France, and even the Soviet Union began developing four-engine bombers, and in 1936, the RAF opted to follow suit. Just as Avro’s twin-engine Manchester was adapted into a four-engine bomber that became the Lancaster, the H.P.55 led to the H.P.56.

It wasn’t exactly an easy task, however, and the aircraft was redesigned considerably, becoming much larger and heavier. The biggest challenge was the switch in the summer of 1937 from two Vulture engines to four Merlins. In September 1937, less than two years before the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe, Handley Page was awarded a contract to manufacture two prototypes for the H.P.57, which then led to an order for 100 bombers.

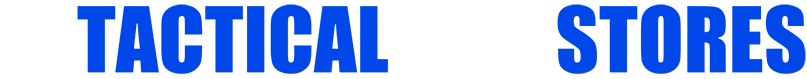

The Halifax Mk I to the Mk III

The original version, the Halifax Mk I, was powered by 1,280 hp Merlin X engines, and the aircraft was outfitted with a 22-foot-long bomb bay featuring six bomb cells in the wing center section. The aircraft’s capacious bomb bay could carry 6,000 kg (13,200 pounds) of bombs, up to 1,800 kg (4,000 pounds) in size, on racks in the fuselage. The original bombers were fitted with rounded tailfins, but these were soon replaced by larger, square surfaces that improved the aircraft’s handling.

Early models were fitted with a twin-gun nose turret, but this was later replaced by a streamlined Perspex moulding, which resulted in less drag. The Mk I modelers were also fitted with Boulton Paul power-operated turrets in the nose and tail, with two .303 (7.7mm) Browning machine guns in the nose and four in the tail. Two Vickers .303 (7.7mm) “K” Guns could also be fired by hand through beam hatches.

The Halifax Mk I could fairly be described as sluggish, but it was significantly improved with the introduction of the Mk III version, which was outfitted with four 1,613-hp (1,204-kW) Bristol Hercules XVI 14-cylinder radial piston engines. In that configuration, the four-engine bomber could reach a maximum speed of 310 mph (500 km/h) at 13,500 feet (4,115 meters), while it had a long-range cruising speed of 215 mph (346 km/h), with a service ceiling of 24,000 feet (7,315 meters). With a full bomb load, the Halifax had a range of 1,030 miles (1,658 km).

One of Halifax’s more unique features was the use of split assembly in its construction. Separate sections of the bomber, including its outer wings, rear fuselage, tail units, and cockpit/nose, were all manufactured independently. This made it possible for multiple components to be fabricated simultaneously, allowing more skilled workers to carry out the construction. That sped the production of the Halifax, but it also allowed the bomber to be disassembled for transportation if it was unable to fly.

The Halifax Goes to War

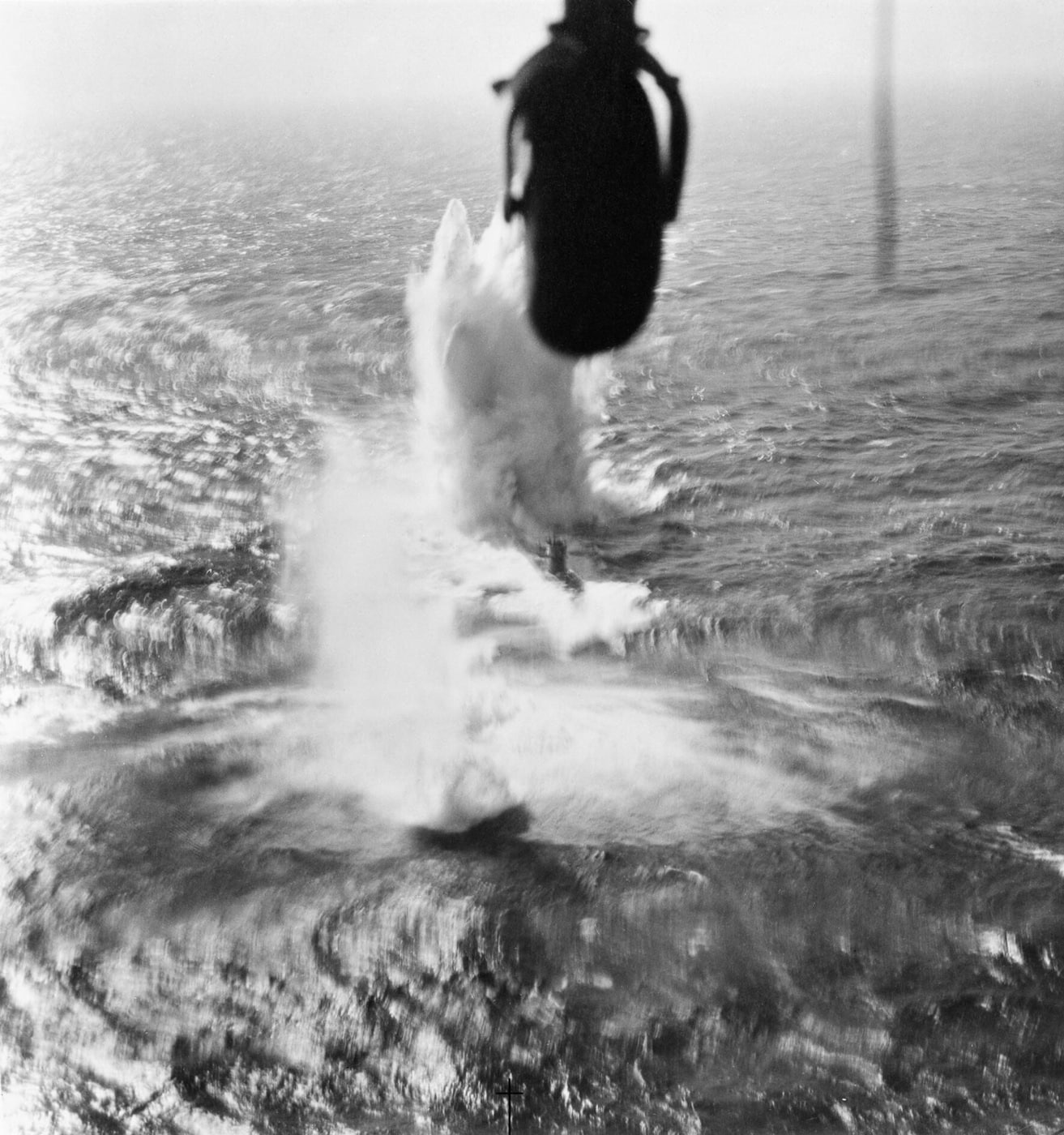

The Handley Page bomber first entered service with No. 35 Squadron at RAF Linton-on-Ouse in November 1940, and crews spent the remainder of the year and the early months of 1941 putting the Halifax through the motions. Finally, on the night of March 10-11, 1941, six Halifax bombers took part in the bombing raid on the occupied French coastal city of Le Havre, targeting the area around the docks.

As with the Lancaster and Stirling, the RAF carried out daylight attacks with the Halifax, but following intense fighter opposition that increased the casualty rates to levels deemed “unsustainable,” the Halifax was withdrawn from daylight bombing missions by the end of 1941. One issue was that, even in tight formations, the bombers simply lacked sufficient firepower to counter enemy fighters.

However, its first daylight raid had occurred in July 1941, when it was employed against the German battleship Scharnhorst, which was docked in La Pallice, France.

At its peak, the Halifax equipped 35 squadrons of RAF Command and took part in 75,532 sorties over Europe between 1941 and 1945. In those missions, the bomber was credited with dropping 231,263 tonnes (227,609 tons) of bombs on enemy targets. As the bombers were primarily employed in nighttime missions, the undersides were painted a dark black to help hide the aircraft from enemy searchlights.

American bombers operating from the UK rarely used their full lifting capacity, as the strategic bombing missions deep into enemy territory required significant fuel reserves, limiting the weight available for bombs. However, the Halifax typically carried near-capacity bomb loads on its operations.

Despite the success of the Avro Lancaster, which greatly overshadowed the Halifax, the Handley Page bomber remained in service with Bomber Command through VE-Day in May 1945.

More Than the Other

The Halifax has earned respect from aviation historians. It has even been described as one of the best aircraft in its class, as it was gifted with immense bomb-carrying capacity, toughness, and, notably for the crews, the toughness to survive when hit.

The Handley Page was also an “all-rounder” aircraft. Beyond its nocturnal raids over Europe, it took on other duties, serving as a pathfinder, where it located and marked targets for other bombers; but it also served well as an aerial ambulance, freighter, glider-tug, personnel transport, and even a maritime reconnaissance aircraft, where it sought out enemy submarines and shipping patrols. The Halifax was also used for meteorological missions.

In those other roles, the aircraft were converted from standard bombers and specially equipped for their new roles, with new designations. RAF Transport Command variants were designated C.Mk III, C.Mk VI, and C.Mk VII, with those aircraft employed for casualty, personnel, and freight transport. No. 138 and No. 161 (Special Duties) Squadrons were also tasked with dropping special agents and/or supplies by parachute into occupied territory, and the Halifax proved well-suited in that role.

Moreover, the Halifax was the only aircraft capable of towing the large General Aircraft Hamilcar glider, which was employed in Operation Tonga, the airborne missions undertaken by the British 6th Airborne Division to support the larger Operation Overlord and the D-Day landings in June 1944. The Halifax glider tugs later carried the Hamilcar gliders during Operation Market Garden and Operation Varsity. During those operations and others, the Handley Page aircraft also acted as glider tugs for the Airspeed Horsa gliders.

Brief Post-War Service

The Halifax was withdrawn from Bomber Command immediately after VJ-Day in August 1945, but the GR.Mk VI continued to serve with the Coast Command after the war, as did the A.Mk VII troop-carrier and supply-drop variants.

A post-war version, the C.Mk VIII, could carry up to 8,000 pounds (3,629 kg) of detachable cargo. It was among the final versions built, along with A.Mk IX trooper-carrier. The final RAF meteorological/weather reconnaissance missions were phased out in 1952.

Civilian-operated Halifaxes were part of the aircraft that carried out supply deliveries during the Berlin Airlift. The last attributed combat operation was carried out by a French Air Force Halifax (sold as surplus after WWII) in French Indochina in 1951. The aircraft remained in service with the Egyptian and Pakistani air forces until the 1950s.

Three Surviving Examples

Even though more than 6,100 were built, only three are now on display. Of these is a glider-tug variant that was used in 1945’s Operation Varsity. That aircraft is now in the collection of the National Air Force Museum of Canada in Trenton, Ontario.

Two bomber models are in museums in the UK.

These include a restored aircraft, HR792, which was crashed in the UK in January 1945 following a year and a half of service. It had served as a chicken coop until it was purchased and restored from parts from other Halifax aircraft. It is now in the Yorkshire Air Museum.

One of the Handley Page Halifax bombers that was part of the raid on the German battleship Tirpitz and which was recovered from a lake in Norway, is now at the RAF Museum in London. It has been left in un-restored condition.

Efforts have been underway to recover two more aircraft; one that made a water landing near Sweden and another near Scotland. The goal is to recover and restore those aircraft to their wartime configuration.

Finally, a nose and forward fuselage were salvaged by aviation collector Graham Trant in the 1960s, who donated them to the Skyfame Collection in 1965. In 1979, it was purchased by the Imperial War Museum, London. However, it is not currently on display.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here