Kamikazes: Stopping the “Divine Wind”

Kamikaze! Even 80 years later, the term still snaps men to attention. The word has become embedded in our language and is still used to describe any vehicle that purposefully executes an attack against a target that ends in its own destruction. In the ongoing war in Ukraine, modern “kamikaze drones” hover above the battlefield, guided by remote pilots to crash into a wide range of targets below.

While the military concept remains the same, the level of terror for the men facing the hell-bent missiles is quite different. The flesh-and-blood Allied sailors that faced the kamikazes fought for their lives against an opponent willing to sacrifice his own life to kill them. It was a visceral, primal form of combat within the context of a modern war.

One Plane/One Ship

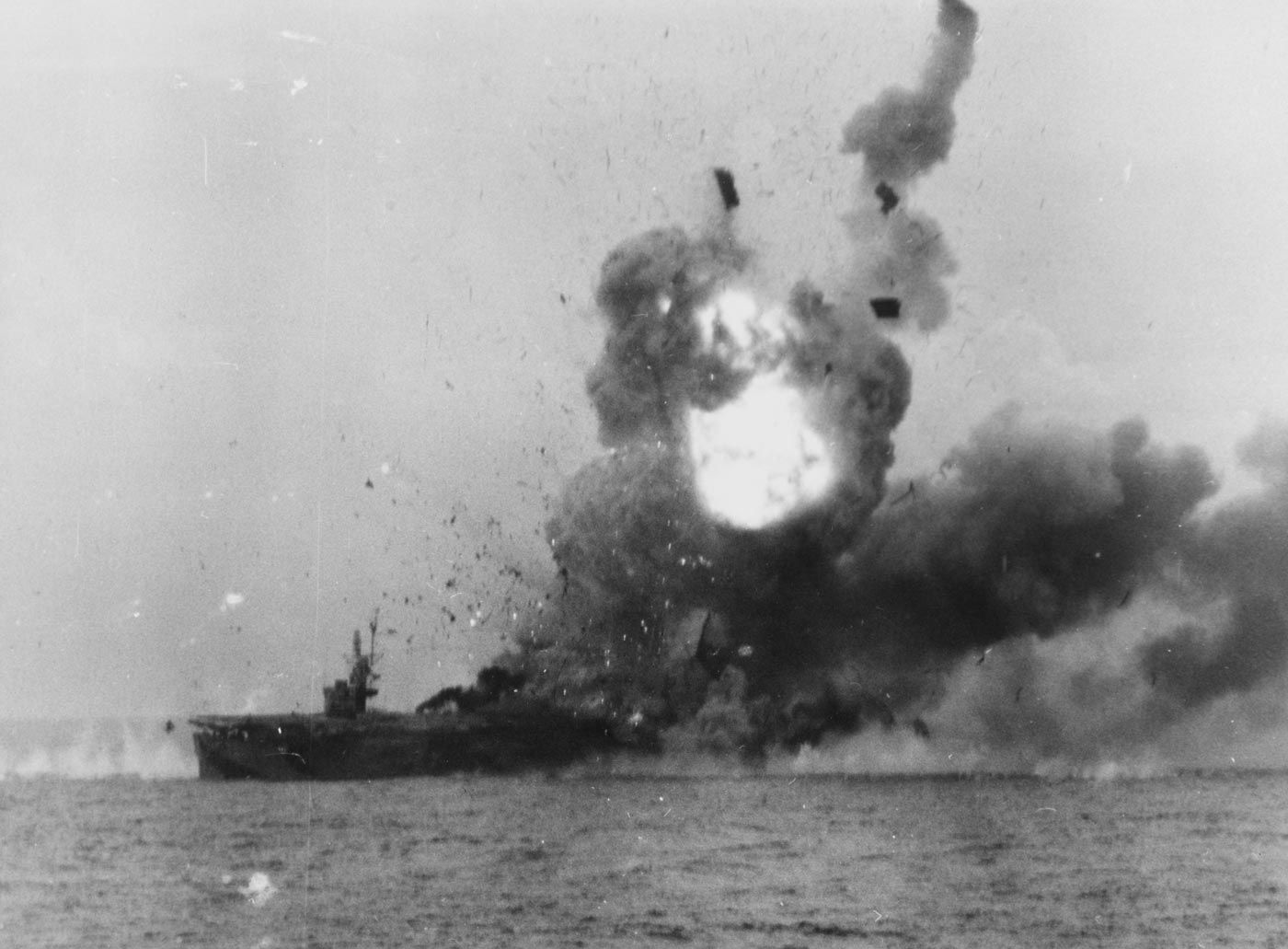

Earlier in WWII, conventional air attacks against Allied surface vessels met with varying degrees of success. By late 1944, the U.S. Navy had achieved operational air and surface superiority over their Japanese opponents. kamikaze attacks threatened to change that dynamic.

Nearly 20% of all Japanese suicide attack planes were successful — and when they struck, they caused massive damage. Research shows that 47 U.S. ships were sunk by kamikaze air attacks, with dozens more damaged.

Beginning in October 1944, and carrying on until the end of the war, the kamikazes made a huge impression on the U.S. Navy as well as the future of naval combat.

For this article, I researched the weapons and tactics the U.S. Navy used to protect its ships and men against what the Japanese called the “Divine Wind”.

The Japanese term “kamikaze” comes from a national legend rooted in meteorology and military history. In the autumn of 1274, the Mongol empire sent a massive invasion fleet, stated to be nearly 1,000 ships, to conquer Japan. Fierce resistance by the samurai caused the Mongol troops to bog down, and then to withdraw to their ships in waters off Kyushu. The sudden appearance of a typhoon destroyed much of the Mongol fleet and miraculously ended the threat.

Seven years later, the Mongols returned, this time with a fleet of supposedly more than 4,000 ships. However, in the intervening years, the Japanese had constructed high walls and other beach obstacles. Unable to find a suitable landing zone, the Mongols lingered for months off the Japanese coast, their men depleted by hunger and illness. And again, a massive typhoon appeared and devastated the Mongol fleet. Most of the survivors were killed by the Japanese.

By World War II, almost every Japanese knew the legends of the “divine winds” that had twice saved their island nation from a huge invasion fleet. It is little wonder then that kamikaze was the name given to the men who would sacrifice their aircraft and their lives to attempt to save Japan with a miracle once again.

This article compiles excerpts from U.S.N. intelligence reports regarding the defense against suicide attack planes.

Types of Ships Targeted

In addition to the destroyers and carriers, nearly every other type of fleet unit has been attacked, including transports, landing craft, merchant ships, minesweepers, battleships, cruisers, tenders, patrol boats and hospital ships. Even an attack on a submarine by a suicide plane has been reported.

A POW who volunteered as a suicide pilot, but failed in his mission, stated that he was ordered to “crash-dive on any large ship”, with preference in this order: Carriers, battleships, cruisers, transports. He denied that there was a deliberate policy of wearing down picket ships, insisting that all suicide attackers prefer to attack larger ships, but sometimes cannot get through the AA fire.

The Japanese Army Training Manual indicates that the targets will be chosen by the senior commander by stating: “The TO Force (ED: “TO” is an abbreviation for TOKUBETSU meaning “special” and referring to the suicide plane units) must sink without fail the targets selected by order of the senior commander, without regard to the size or type of the enemy vessel.” The manual makes no recommendations concerning the types of vessels to be hit. The selection of types will naturally depend upon the local tactical situation and, for this reason, has probably been excluded from the book. The only type of vessel with which the manual appears to be concerned is the carrier. A chart showing the possible armament and vulnerable points on the ESSEX-class carrier is included in the manual. In addition, the text cautions personnel to learn to distinguish carriers from tankers and landing craft.

Evasive Tactics

The report of the USS Kimberly (DD-521), describing an attack which occurred on the afternoon of March 25, 1945 off Kerama Retto, describes the hard-turning evasive maneuver of the destroyer:

“At this time (after bogies were picked up) emergency flank speed was rung up and fire was opened on the VALs on a relative bearing of 0700 at advanced range of 7500 yards. Both VALs turned away, proceeded outside effective gun range and firing was ceased. Almost simultaneously with “cease firing”, one of the VALs peeled off and began to close the range on a converging but nearly opposite course. Fire was immediately re-opened and the rudder put hard right to maintain all guns bearing as the relative target bearing rapidly dropped aft. During this phase of the approach, the fire control problem was one of an extremely high deflection rate which the pilot further complicated by resorting to radical maneuvers, including zooming, climbing, slipping, skidding, accelerating, decelerating and even slow rolling. He continued to close the range on a circling course, indicating his intention to get on our “tail” and further indicating to all observers his ultimate intention. By this time the range had closed to 4000 yards and all bearing 40 mm mounts opened fire. The plane was now in a vertical right bank, circling to come in from astern. The target seemed to be completely surrounded with 5-inch bursts and 40 mm tracers. At about 1500 yards range on relative bearing 1700 he leveled off and came straight in at an altitude of about 150 feet, performing continuous right and left skids. The ship was still turning with full right rudder, but the target skidded to always remain inside the ship’s wake. At 1200 yards all the bearing 20 mm guns opened fire, and at about this same time the previously faint line of smoke coming from the plane became a positive stream of black smoke, but still the target kept coming. Now only the after guns would bear and each 5-inch salvo blasted the 20 mm crews off their feet. Despite this difficulty, at the instant the VAL passed over the stern, the 20 mm guns had managed to empty one complete magazine. The plane was now about 100 feet in the air and apparently headed for the bridge with 40 mm guns Nos. 3 and 5 still firing at maximum rate. Just as the plane reached a point above 40 mm gun No. 5, it went out of control and fell nearly vertically between 5-inch mounts Nos. 3 and 4 crashing into the still rapidly firing guns of 40 mm mount No. 5.

The intensity of the explosion and the nature of the damage indicated that the VAL was armed with a bomb with an instantaneous fuse. The estimated size of the explosive was about 200 pounds.”

Four crewmen of the Kimberly were killed, and 57 wounded, during this attack.

Types of Attacks

Generally, the approaches are of four different types. In one, the suicide plane picks the target from long range and makes a long, straight dive from about five miles. Escorting planes disperse and turn back to confuse the radar. Other planes hide in the cloud cover after their escorts have left, then dive on unsuspecting ships.

Some attacks have been coordinated with high-level bombers that draw attention away from the suicide attackers. The fourth, and most common, is the low-level approach. In this, planes come in low over the water, then climb steeply for their final dive so that radar and fire control seldom have sufficient time to take effective action.

Charts and text of the captured Japanese Army manual give additional details of three types of approach; the horizontal, the diving, and the bow-on. In addition, the document recommends that “while advancing every effort must be made to take good advantage of local weather conditions, that is of clouds, sun and wind direction, with due regard for general climatic conditions. This will be especially the case in daylight and surprise attacks.”

The document states that the formation for the advance “will depend on conditions, particularly on the attack method, on the strength used and on the dispositions of the enemy.” It is particularly advantageous, the manual states, “to deceive the enemy by adopting formations and maneuvers which resemble those of his carrier-borne aircraft.”

For the most part, a high-altitude, high-speed approach was recommended, while in a surprise raid an extremely low-altitude approach was considered best. The actual attack procedure was described in the manual as quoted below.

“As soon as the attack targets are discovered, the pilots will first pull the fuse arming vane release handle and then close the attack on the enemy by diving down on him at full speed. At this time, every effort must be made to avoid losses from the enemy CAP and AA barrage by appropriate plane maneuvers. The run-in for steep diving attack will differ with the type of plane, but the approach to the enemy will be at high altitude. Then altitude and speed will be successively adjusted—this varies with the situation, but it will be best to adjust the speed twice—at 6000 meters and 4000 meters.”

Concerning the low-level attack, the manual states: “In the run-in for an extreme low level horizontal attack, the enemy will be approached at high altitude and then by rapid plane maneuvers, speed and altitude will gradually be adjusted.

A very low-level horizontal attack in a surprise raid when the cloud height is low will use either a diving or horizontal collision, depending on conditions at the time, and will be made with plane types such as Ki 67 (Peggy), Ki 45 (Nick), etc., at night, dawn or dusk.”

BAKA

Those who have observed BAKA attacks say that a trail of “light brownish smoke” comes from the bomb just before its release from the mother plane. As the BAKA is launched, the bomber veers off, showing its underside to the target. The smoke continues to trail BAKA in its path to the target. It was observed in some reports that at times the smoke can still be seen when the bomb is almost invisible because of its high speed. One report cautioned gunners who see smoke but no bomb to expect a low approach over the water.

Although combat experience with the BAKA was still relatively slight at that point, encouraging reports had come from the Fleet, indicating that the rocket bomb could be brought down by anti-aircraft fire. In one instance, a DM (converted minelayer) splashed a BAKA with a 5-inch gun, and, in another, an AM (auxiliary mine layer) blew one apart with a 40 mm battery.

Types of Explosives Carried

Explosives carried in suicide planes ranged widely. In the earlier attacks, mortar shells, artillery shells and other miscellaneous types of ammunition were found in wrecked planes. Then, it had been customary for kamikazes to carry a 250 kg bomb.

At times, the planes crashed without releasing the bombs, but later the tendency had been to release the bomb, either on another ship, or just before crashing. In some instances, the bombs exploded before the planes hit, either because of the pilots’ action or because they were hit by AA fire. Some suicide planes also had carried torpedoes, sometimes inside the plane. In one case, the torpedo was released just before the plane crashed and exploded within the ship. In another instance, a suicide plane carried an eight-inch shell as its explosive, but such cases were much rarer than they were when the kamikaze attacks first started.

Pilot Quality

The quality of the suicide pilot varies. One POW claimed he was flying his first combat mission. In contrast, many pilots demonstrated lengthy flying experience by their skillful evasive tactics and careful deliberation in their choice and approach to targets. One pilot’s blouse, recovered after a suicide attack, indicated that he was a carrier pilot, the most experienced type of Japanese airman. He was wearing a ribbon with two stars, possibly for combat experience. One action report noted that the Japanese were using more experienced pilots for suicide dives off Okinawa than they did in the Philippines.

The answer is that Japan uses any pilot who volunteers or might order any others on such a mission. The quality of such a group naturally varied widely. There was no evidence, however, to show that the best of Japan’s pilots were exempt from kamikaze squadrons to fly more orthodox combat missions. Some pilots doubtlessly volunteered in the belief that the Japanese warrior gains automatic enshrinement and a future life as a protecting deity (Kami) of Japan if he made this supreme gesture of devotion.

U.S. Navy Defense Recommendations

Numerous recommendations for countermeasures were made by officers of the Fleet who had experienced suicide attacks. Many were already being tried, with varying degrees of success. The most common recommendations were:

- Heavier concentration of AA fire.

- Alteration of gunsights for firing at close-in, fast-moving targets.

- Grouping of ships for mutual protection on picket stations.

- Violent evasive maneuvers by smaller, highly maneuverable ships.

- Continual air coverage of picket vessels.

AA Fire Kills the Most Kamikazes

Suicide planes present a special problem to AA gunners, because the pilots seldom exhibit fear of an AA barrage. Instances have been reported of kamikazes continuing their dive, although severely damaged and afire. One continued in after both wings had been shot away. Ordinarily, a direct hit, blowing up the plane in air, is sufficient to stop the attack. Effective AA fire is made difficult not only by the evasive maneuvers of the plane, but also because many of the planes have armor in vital spots and self-sealing gas tanks. Furthermore, ships usually have no more than 20 seconds to destroy planes, once they come into range.

Despite such difficulties, it has been anti-aircraft fire which accounted for the greatest number of suicide planes. A high echelon action summary after the Leyte and Lingayen operations estimated that approximately half of the planes committed to suicide missions were shot down by anti-aircraft fire before reaching their objectives. Another one-sixth, it was estimated, were destroyed by the Combat Air Patrol. Thus, about two planes in three were destroyed before reaching their target.

Antiaircraft Action Summary “Suicide Attacks” April 30, 1945

The suicide attack represents by far the most difficult anti-aircraft problem yet faced by the fleet. The psychological value of AA, which in the past has driven away a large percentage of potential attackers, is inoperative against the suicide plane. If the plane is not shot down or so severely damaged that its control is impaired, it almost inevitably will hit its target.

Expert aviation opinion agrees that an unhindered and undamaged plane has virtually a 100 percent chance of crashing into a ship of any size regardless of her evasive action. At the present time ships are destroying more than 50 percent of all attacking suicide planes, as compared with 33.6 percent success against dive and torpedo attacks during the first half of 1944.

Conventional attackers normally turned away in the face of a tremendous AA barrage, to live to fight another day. Suicide attackers pressed on regardless of the fire directed at them.

Summarizing, analysis of AA actions shows:

- 1,444 suicide and non-suicide planes were taken under fire.

- 352 suicide planes approached within gun range.

- 40 (11 percent) of these were shot down before committing themselves to a crash attempt.

- 312 suicide attempts were made on ships.

- 191 (61 percent) were shot down or deflected, but of these 53 (17 percent), crashed close enough to ships to damage them.

- 1092 non-suicide planes were taken under fire.

- 156 (14 percent), were shot down.

- 23 (1.2 percent), scored hits on ships.

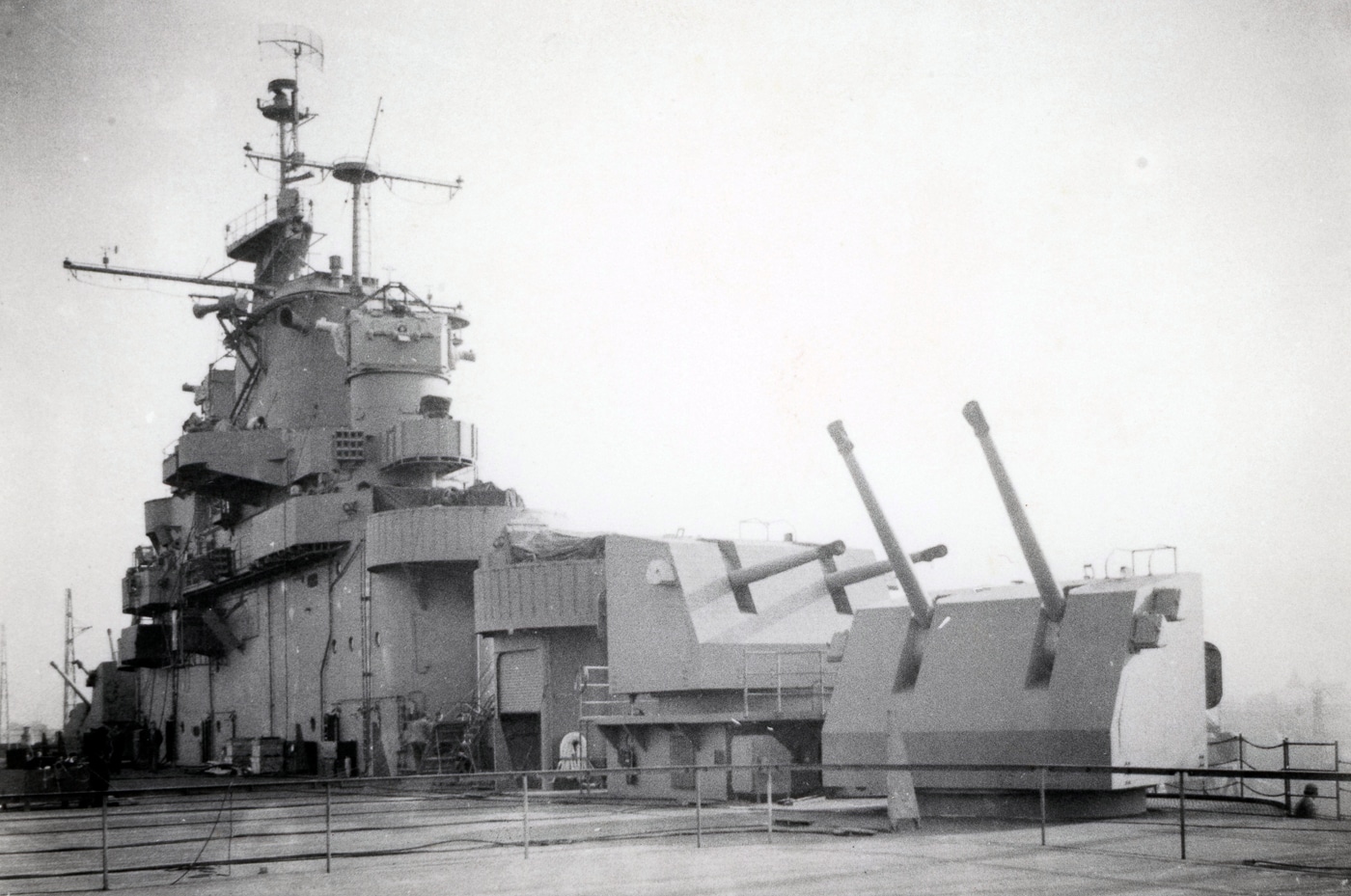

The U.S. Navy’s AA Guns

Despite the U.S. Naval Aviation’s technological supremacy over Japanese aircraft, U.S.N. Combat Air Patrols (CAP) were simply not enough to cover the entirety of the massive invasion fleets. While large groups of kamikazes gathered to attack the vital American carriers, many suicide planes came in small groups or individual attacks. Many of the latter fell on the isolated picket destroyers and similar vessels. Their desperate gun battles with the kamikazes came down to the effectiveness of their guns, and the gun crews fighting for their lives.

5-inch/38 gun

“Without any doubt the Commanding Officer considers the 5″ gun using the Mark 53 VT projectile as the most effective weapon against suicide planes.” (Commanding Officer, Destroyer Squadron Two)

As described in the preceding U.S. Navy reports, the 5″/38 gun provided the best opportunity to destroy kamikazes at a safe distance. By almost all accounts, the U.S. Navy’s 5-inch gun, coupled with the Mark 37 Gun Fire Control System, dual-purpose naval gun of the war. When used with new “VT-fuse” shells, the 5-inch guns could create a cloud of shrapnel during barrage fire—powerful enough to tear off wings and tails of attacking aircraft.

The turret-mounted 5-inch guns had a high rate of fire, about 15 rounds per minute as a baseline. Experienced gun crews could reach up to 22 rounds per minute during critical short periods. Even the older pedestal mounted 5-inch guns could reach 12 rounds per minute in AA fire. The average barrel life for the 5-inch gun was about 4,500 rounds. The 5-inch rounds provided the U.S.N.’s most reliable “kill-stop” against aircraft.

40mm Bofors

“Accurate 40mm fire will knock down a suicider. More intensive target practice should be mandatory for all 40mm gun crews.” (Commanding Officer, Destroyer Squadron Two)

The U.S. military began license-built production of the highly effective, Swedish-designed Bofors 40mm L/60 gun during 1941. Most of the U.S. Navy’s 40mm guns were water-cooled variants of the automatic dual-purpose gun (140 rpm maximum). The 40mm guns used a 4-round ammunition clip (about 20 pounds per clip) with automatic extraction and an integrated cam-operated, recoil-powered autoloader.

Production increased steadily during the war and by 1943 the 40mm Bofors gun was the U.S. Navy’s most numerous AA gun and accounted for nearly half of all Japanese aircraft shot down by U.S. Navy AA fire during the war. After 1943, the 40mm guns became more accurate when they were coupled with the Mark 14 gunsight—which used two gyros to calculate the lead angle to the target while projecting an aiming point for the gunner. Additional accuracy was gained when the Mark 14 sight was integrated into the advanced Mark 51 Gun Director System.

The Navy’s 40mm guns were provided in single, double, and quadruple mounts, and they did the lion’s share of kamikaze killing, their high rate of fire and overall accuracy were indispensable. While the 40mm shells were powerful, they were not entirely reliable as a “kill-stop” munition, and the 40mm warhead was too small to be fitted with a VT proximity fuse.

20mm Oerlikon

“Although the gun may score many hits at close range, it does not destroy the plane in time to prevent a suicide crash.” (Commanding Officer, Destroyer Squadron Two)

With World War II on the horizon, and with attack aircraft rapidly growing in size and speed, U.S. Ordnance sought a replacement for the .50 caliber M2 Browning (water-cooled) AA machine gun.

The Bureau of Ordnance quickly settled on the Swiss-made 20mm Oerlikon Mark I. U.S. manufacture of the 20mm gun began in the summer of 1941, nearly 125,000 Oerlikon guns were made in America by the end of WWII. The 20mm guns were accurate and fast-firing—an experienced crew fed the gun’s 60-round drum magazines to achieve a 300 rpm cyclic rate.

Until the advent of the kamikaze, the Oerlikon guns were first-rate short range AA guns (1,000-yard effective range). However, when facing fanatical suicide aircraft, its lightweight HE shell (just 4.3 oz) was unable to provide the “kill-stop” that the U.S. Navy required. Consequently, during early 1945, the U.S. Navy replaced as many 20mm guns with the 40mm Bofors as possible.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

The post Kamikazes: Stopping the “Divine Wind” appeared first on The Armory Life.

Read the full article here