Remembering the USS Maine

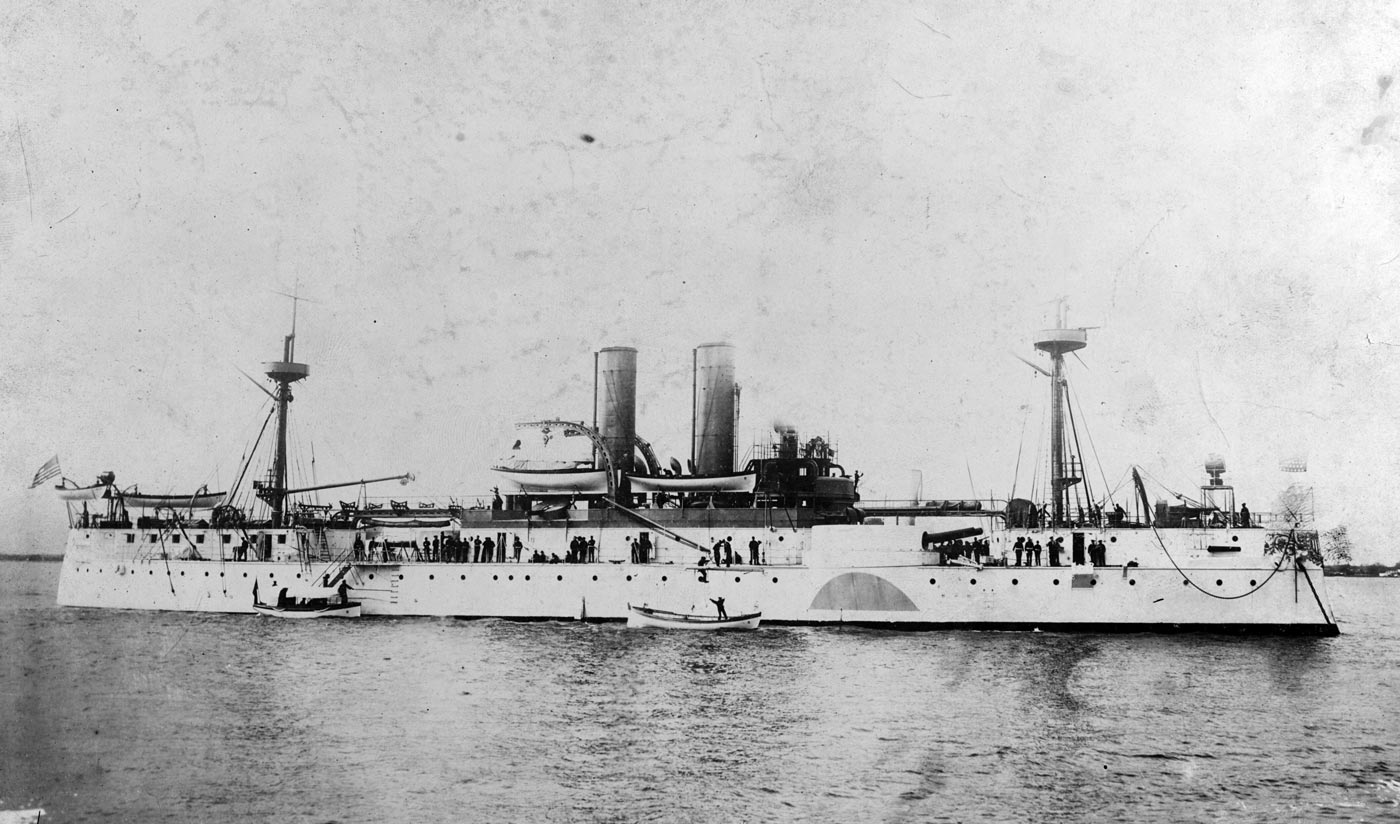

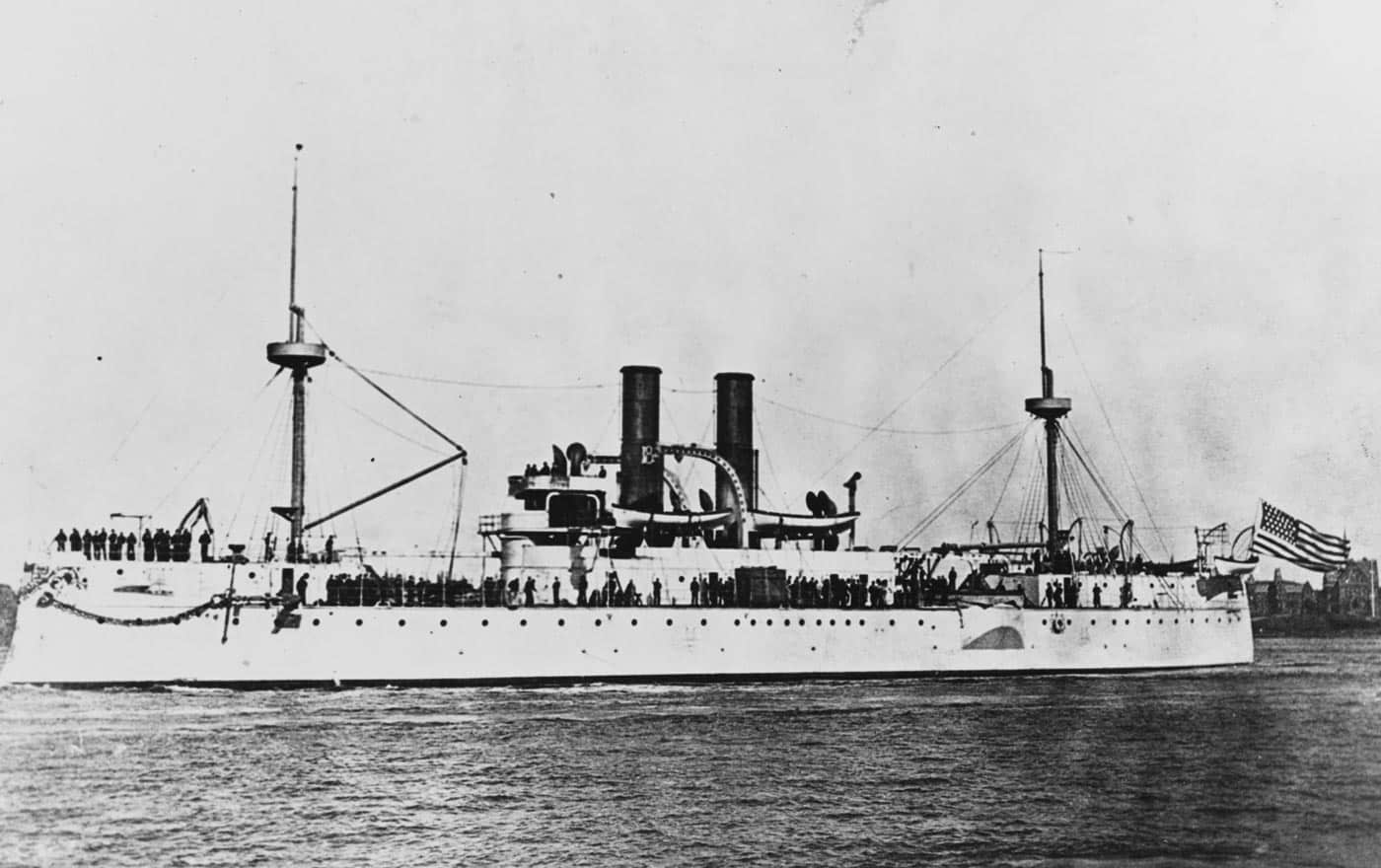

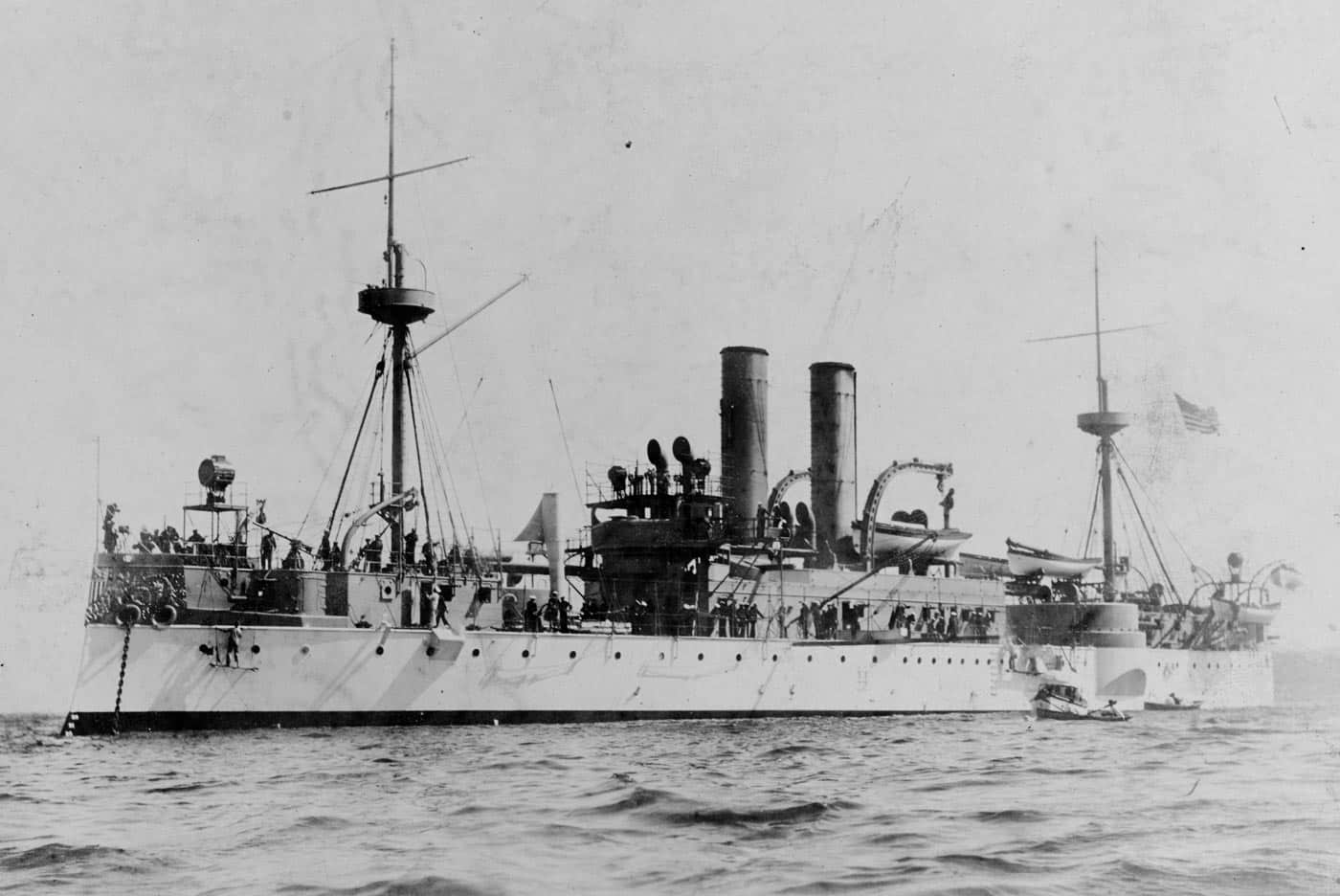

On February 15, 1898, the United States Navy “second-class” battleship USS Maine exploded while anchored in the harbor at Havana, Cuba — which was then a colony of Spain. A large number of the crew of the warship was killed in the explosion, and it prompted widespread outrage that led the United States to war with Spain.

Historians aren’t universally convinced the explosion resulted from sabotage, but that is hardly a new revelation.

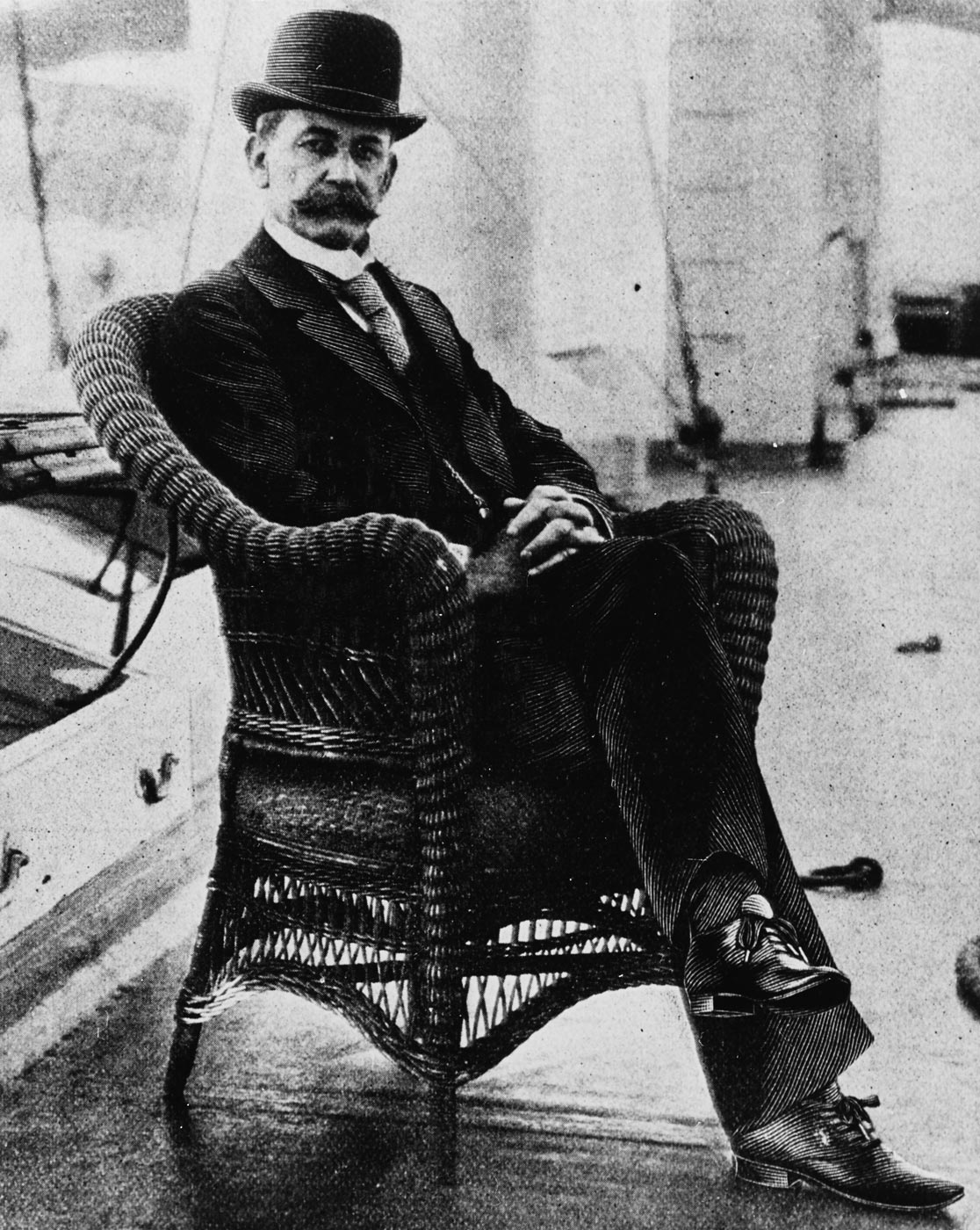

Even Captain Charles Sigsbee, the warship’s commanding officer, believed that the explosion could have been internal, and he urged caution until a complete investigation could be conducted. At the same time, President William McKinley refused to panic or to urge war.

Yet, the rallying cry “Remember the Maine” stirred up great resentment, and trouble had long been brewing on the island for some time. As Cuba was in a state of insurrection, the USS Maine had been dispatched to Havana to protect U.S. interests. In fact, its explosion was merely the catalyst that resulted in war. It was a conflict that is remembered for being rather lopsided, with the U.S. seeing decisive victories on both land and sea in Cuba and the Philippines. However, less than 15 years earlier, the United States Navy would have been in no shape to even wage war against Spain, much less achieve such a victory.

Rebuilding the U.S. Navy

An important part of the history of the U.S. Navy is that it has shown repeatedly it is more than able to increase rapidly when the need arises. During the American Civil War, the sea service expanded from what has been described as a “pygmy navy” to the world’s largest in just four short years.

However, it didn’t last long and, less than 20 years later the state of the U.S. Navy was in such bad shape Congress called for replacing its obsolete fleet. The goal wasn’t to raise the United States to the status of a major naval power, as that would come later (just in time for the war against Spain).

Instead, in the mid-1880s, the U.S. Navy received two sea-going armored warships — the USS Texas and the USS Maine, similar but still two different classes of ships. As a matter of clarification, the former is not the New York-class battleship now undergoing major renovations in Galveston, but the preceding vessel that also was named for the Lone Star State. Moreover, both warships were originally described as armored cruisers but were redesignated as second-class battleships before they were commissioned.

The term “second-class” battleship essentially meant they were less heavily armored and armed than the “first-class” battleships of the day.

Not a Fully Original Design

Even though they weren’t quite on par with the capital warships in service in Europe, USS Texas and USS Maine still had the distinction of being the U.S. Navy’s first true battleships.

The design for USS Maine wasn’t entirely new or revolutionary. Instead, it was greatly influenced by the need to counter regional threats, including those from Latin America. At the time, a naval arms race was underway in South America, and Brazil acquired the British-built battleships Riachuelo and Aquidaban. The U.S. Navy Department looked to the British-built warships, and the design for the Maine strongly resembled the former Brazilian vessel, which was the most powerful warship in the Western Hemisphere at the time.

USS Maine was authorized by an Act of Congress on August 3, 1886 — and was part of the “New Steel Navy” that included the three cruisers USS Atlanta, USS Boston, and USS Chicago. Upon her completion, the USS Maine was the largest ship designed by the U.S. Navy. As noted, the ship was originally designated Armored Cruiser No. 1 (ACR-1) but was reclassified before she was launched.

That wasn’t the only change she would undergo.

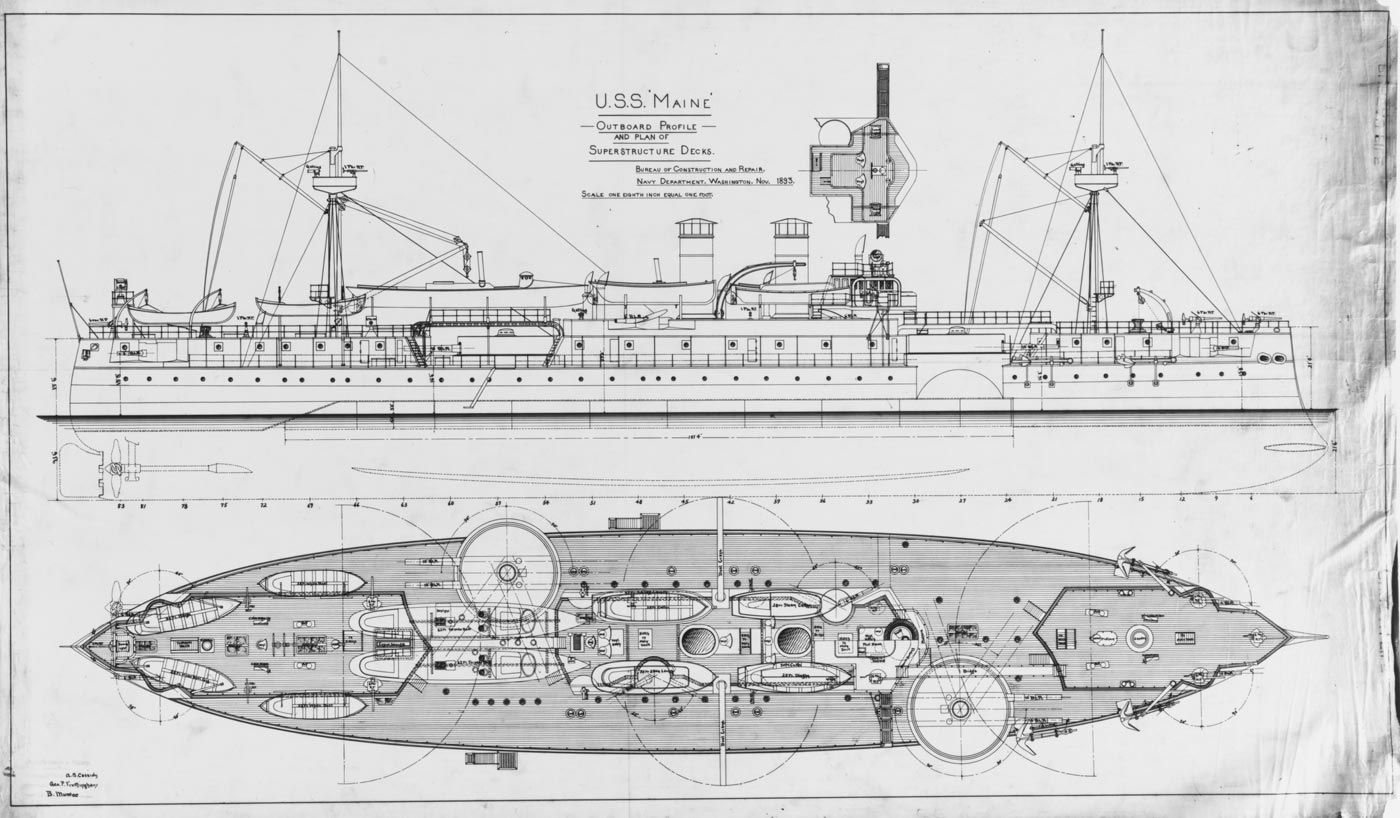

Initial plans called for the USS Maine to have three masts and a rig for two-thirds full sail power — as it should be remembered that this was still the era where steam propulsion was coming into its own. Sails were seen as essential auxiliary propulsion, which could allow the warships to travel long distances when steam power wasn’t sufficient. That would further allow the ships to conserve coal during long voyages. As the technology for steam engines advanced, the naval architects decided that the warship should rely exclusively on steam power.

The warship’s keel was laid down on October 17, 1888, at the New York Naval Shipyard, Brooklyn, New York, and USS Maine was launched just over two years later on November 18, 1890. According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, “Twenty thousand people attended the launching ceremony overseen by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Tracy, whose granddaughter, 12-year-old Alice Tracy Wilmerding, christened Maine with a bottle of champagne from San Bernardino, California. Workmen removed the keel blocks at 11:00 a.m., and Maine slid into the East River. At the time of launch, the ship was the largest ever built in a U.S. Navy Yard.”

Considerable Endeavor

It took an additional five years for the ship to be completed, in part because the shipbuilders were still getting their proverbial “sea legs.”

USS Maine was something of a modern marvel of sorts for the U.S. Navy, powered by two Quintard vertical triple-expansion engines with eight cylindrical boilers that provided the battleship with a top speed of 17 knots. The coal bunkers, which had a capacity of just 895 tons, were placed around the perimeter of the ship’s hull — with the belief that it would provide extra protection to the magazines, which were positioned inboard of the bunkers. Instead of acting as extra armor, the placement may have been a fatal flaw.

As a second-class battleship, USS Maine‘s armor belt was 180 feet (55 meters) long and six to 11 inches (152 to 279 mm) thick, while the vessel’s barbettes were protected by 12-inch (305mm) thick armor. The deck also had two to four inches (51 to 102 mm) of armor plating. The main armament consisted of two turrets mounted en echelon (projected off to either side) that included a total of four 10-inch (254 mm) guns. The turrets were also protected with eight inches (203 mm) of armor.

While the layout of the turrets wasn’t unheard of at the time — and warships such as the Royal Navy’s HMS Flexible and the Italian Navy’s Italia offered similar designs — it severely limited USS Maine‘s ability to fire a broadside. Though there was a break in the center line of the superstructure that theoretically allowed for both turrets to fire on either beam, there was a danger of blast damage to the superstructure. It was far from the only design issue for the warship.

The limited amount of coal meant that the second-class battleship couldn’t operate at sea for lengthy periods of time, nor could it operate at high speeds for extended lengths as coal consumption greatly increased. In addition, when the warship was completed and fully fitted out, it was discovered that the bow section had a draft of about three feet (or one meter) deeper than the stern. That was the result of a mistake in the loading plan, and as a result, 48 tons (43.5 tonnes) of ballast had to be loaded near the stern, resulting in additional unplanned weight!

Short Career

USS Maine was commissioned at the New York Navy Yard on September 17, 1895, and the ship soon became the home for 31 officers and 346 sailors and Marines.

As the fitting-out was being completed at the naval yard, the crew managed to find no shortage of troubles thanks to New York City’s bars and “other attractions.” After more than a dozen crewmen went over their allotted leave, liberty was canceled.

USS Maine finally departed New York on November 4, 1895, and thousands lined up to see the warship head to sea. She spent much of her active career operating along the East Coast of the United States and the Caribbean. In January 1898, she was deployed from Key West, Florida, to Havana to protect U.S. interests as the island colony of Spain was facing a local insurrection and civil disturbances. Just three weeks later, the second-class battleship exploded in Havana Harbor.

Most of the crew were sleeping or resting in the enlisted quarters at the front of the ship. As a result, 236 men were killed, and eight more died from their injuries. Capt. Sigsbee and most of the officers survived because their quarters were located in the aft portion of the ship.

A Spanish board of inquiry argued that the bent hull plating made it clear that the explosion had been internal. However, on March 28, 1898, a U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry declared that a naval mine had been the cause of the explosion. That fact, along with a push from the media at the time (during the age of Yellow Journalism), made it that on April 8, 1898, President McKinley bowed to public pressure — despite Spain’s pledge to institute reforms in Cuba. The U.S. announced it would support Cuban independence.

By the end of the month, the two nations were at war.

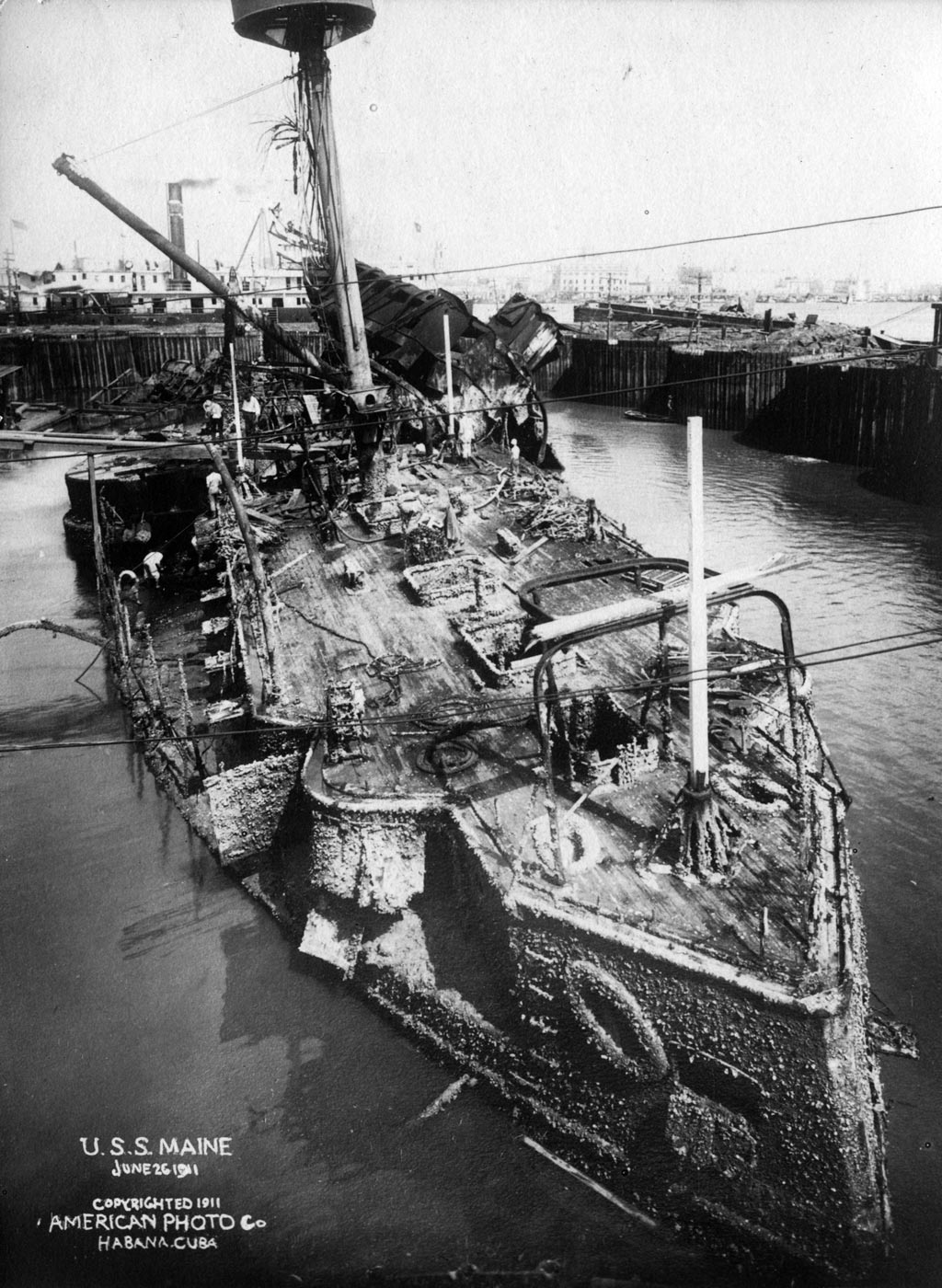

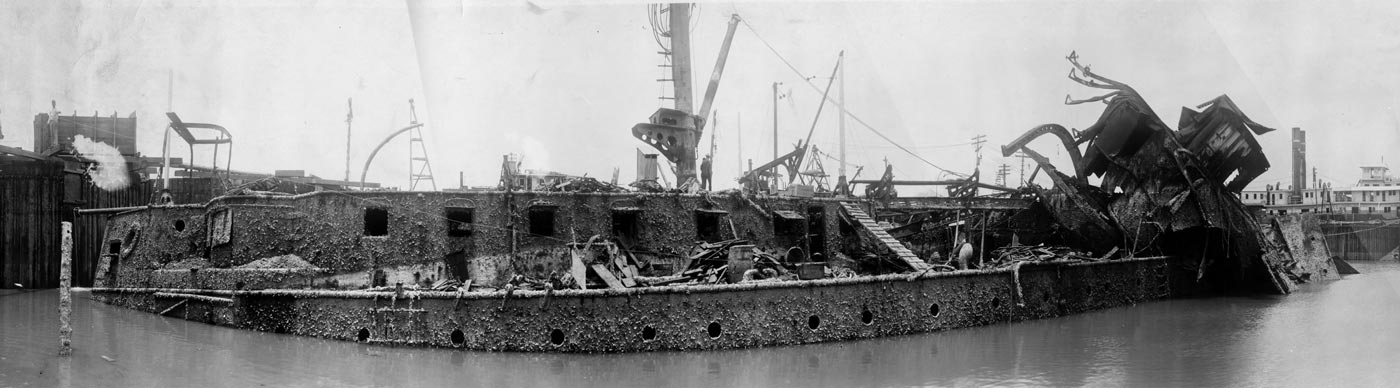

The wreck of the USS Maine remained in Havana Harbor during and even after the Spanish-American War. It was only in May 1910 that Congress finally authorized the funds to remove around 70 bodies still inside the warship, with the remains interned at Arlington National Cemetery. Recovering the warship was no small affair and required the United States Army Corps of Engineers to build a cofferdam around the wreck.

After the bodies were recovered and the ship was raised, it was towed — while escorted by the armored cruiser USS North Carolina and the light cruiser USS Birmingham — and sunk again off the coast of Cuba. That time, it was to the sound of taps and a 21-gun salute.

Was It Sabotage?

Since the sinking of the USS Maine, there have been multiple major investigations and even today, experts cannot agree whether the explosion was caused by a mine or by spontaneous combustion in one of the ship’s coal bunkers — which were positioned outside of the ship’s powder magazines.

Later investigations found that more than 5.1 tons (5 tons) of powder charges for USS Maine for the main 10-inch and secondary six-inch (152 mm) guns had also detonated, virtually obliterating the forward third of the ship. That could have resulted in the bent hull plating that the Spanish board noted. Another investigation of the wreck in 1911 found the bottom hull plates were bent inwards and back, supporting the mine theory.

It was in 1976 that a hypothesis was made that a spontaneous explosion of coal dust caused the warship’s destruction. This wasn’t seen as a wild theory — far from it. There had been a cordite explosion on the Royal Navy’s HMS Revenge in 1899 in one of its 6-inch magazines, but the damage wasn’t severe as only three cartridges detonated. However, a similar incident occurred on the Japanese pre-dreadnought battleship Mikasa in 1905, while several warships saw shells or powder detonate due to improper storage during the First World War.

Though a definitive answer might never come, the USS Maine and her destruction indeed had a lasting impact.

As the Naval History and Heritage Command suggested, “Few ships have had as great an impact on modern U.S. history as Maine. A representative of America’s new industrial and naval power in the 1890s, the ship was launched as the United States started to step onto the world stage. Maine’s loss sparked a war that made the United States a global colonial power, embroiled in long-lasting imperial projects in Asia, the Caribbean, Latin America and the Pacific.”

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here