Rethinking Rifling

Here we examine the twists and turns of early rifling development.

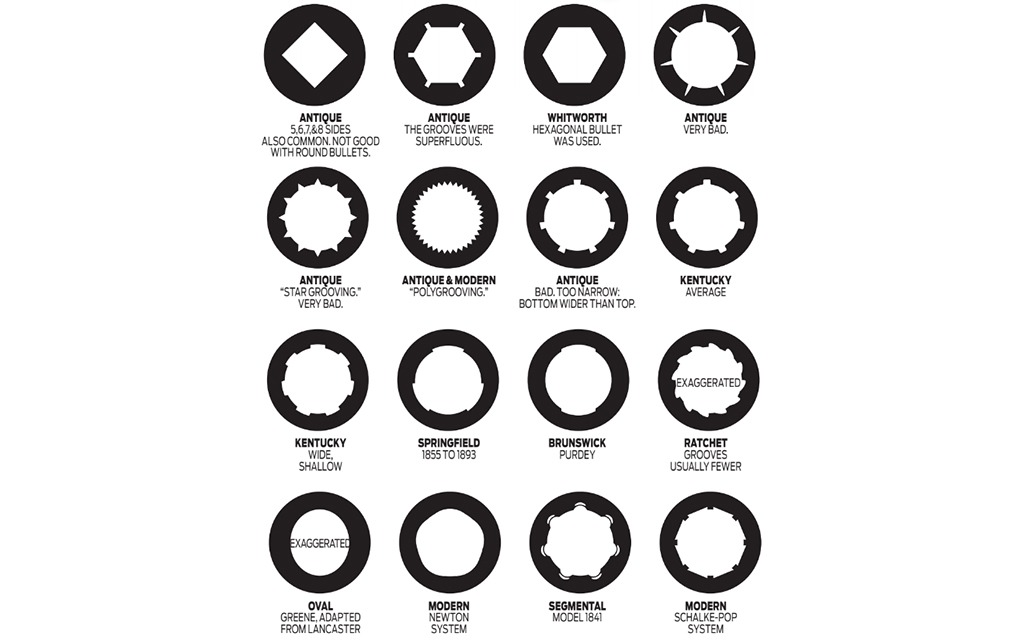

In the 1500s, spiral grooves cut into gun bores were used to spin-stabilize bullets fired through them. While the method of creating these grooves has changed, this system has remained the same and is considered “best” by nearly all barrel makers.

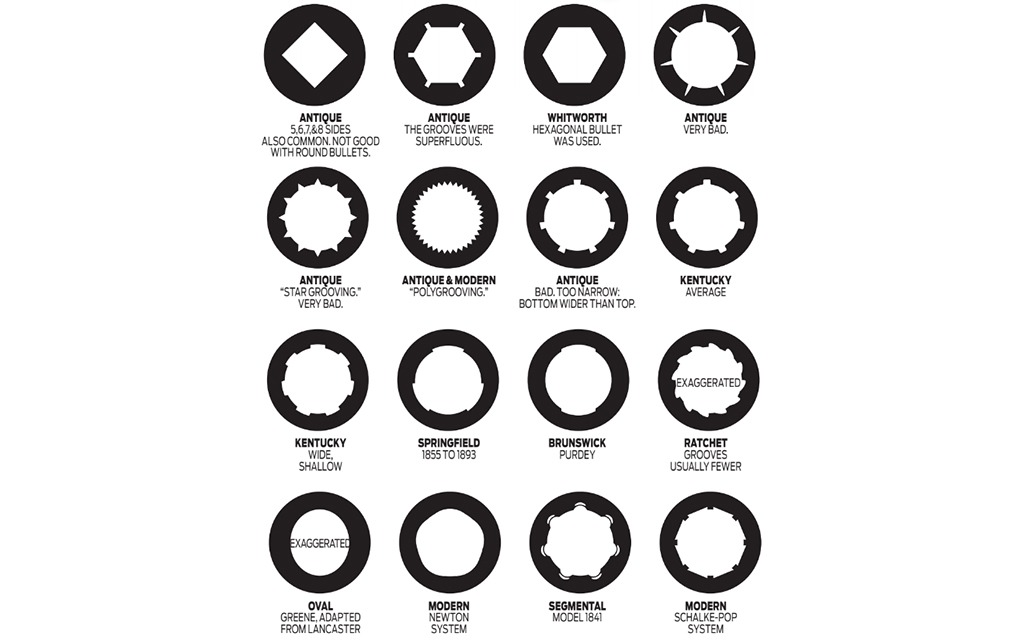

Attempts to improve land-and-groove rifling included choke boring, free boring, gain twist, deep and shallow grooves, few and many grooves, and odd and even numbers. No one system demonstrated significant superiority over another. About 1850, the first alternatives to land and groove (L&G) rifling made their appearance.

Charles Lancaster was considered the first to produce a rifled barrel using a spiral bore in England. Referred to as oval or elliptical boring, the oval interior was turned as though a straight oval tube was twisted, causing a bullet fired through it to be swaged into a slightly oval shape and spun as it traveled down the bore. The idea (in part) was to create a barrel that would perform equally well with a solid bullet or a charge of shot, but that goal did not succeed if experiments firing shot loads through rifled shotgun barrels are any indication. Nevertheless, the system worked with solid bullets. The success was tempered, for blackpowder fouling presented a more significant problem than a deep-groove rifled barrel.

The Civil War saw the Greene Oval Bore Rifle, an early bolt action wherein two bullets were loaded, with the second bullet with its powder charge acting as a gas check behind the charge of the first load. When the action fouled, the rifle had to be used as a muzzleloader. They were made in America with machinery bought from Lancaster. Recovered bullets from Antietam indicate some use.

A similar spiral-bore effort used polygonal rifling. While it is unknown who produced the first such barrel, the best-known effort was by Sir Joseph Whitworth in England in 1853. While the hexagonal-bore Whitworth could be fired with a cylindrical bullet, it was soon found that the best accuracy was obtained only with a six-sided bullet contoured to a mechanical fit.

Semi-military Whitworth rifles, equipped with telescopic sights, were used by Confederate sharpshooters to pick off several Union officers. Major General John Sedgwick was the most famous who was killed by a single bullet at more than 500 yards. The system was also successfully used in artillery pieces, two of which were employed by Confederates at Gettysburg.

The last rifling innovation of the 19th century came in 1871, the work of William E. Metford, a British engineer. Metford’s system utilized shallow rifling with rounded lands, which reduced the bullet’s drag and deformation. Accuracy was excellent, and the design was used in the British military rifle designed by James Paris Lee in 1888.

Unfortunately, highly erosive smokeless powders and corrosive primers soon degraded the accuracy of the soft-steel barrels of the day. A similar system was used in Japanese Arisaka rifles, which benefited from better steel and maintained accuracy better than conventional L&G barrels. Barrels made in America by Charles Newton also used this system, utilizing five rounded lands and grooves.

In 1901, the first head-to-head tests of an oval-boring system versus conventional rifling began at the Springfield Armory. The details are fully documented in the Annual Reports of the War Department for the Fiscal year ended June 30, 1902, Volume VII, Reports of the Chief of Ordnance and Board of Ordnance and Fortification, Appendix XII.

The project began July 16, 1901, with the following letter to the Chief of Ordnance:

“Dear Sir: I have invented a gun with an elliptical bore of .30 caliber, suitable to take the ordinary fixed ammunition of this caliber. I desire to have a thorough Government test, such as will demonstrate the quality of the gun for service. I desire to have the test made at the earliest convenience in order that I may be present.

Very Respectfully, W.F. Cole M.D.”

The Chief of Ordnance was Brigadier-General A.R. Buffington, inventor of the Buffington “wind gauge” sight—the most sophisticated military type of its day—used on the M-1884 and M-1888 Springfield rifles and carbines. General Buffington ordered, “test without delay the gun presented by Dr. Cole” and invited Cole to attend the tests.

Two days later, Dr. Cole met with the Board to test his rifle, which had the same 30-inch barrel as the Krag and used the same ammunition. “The cross-section of the bore is an ellipse the short diameter being .30 inches, the long diameter .31 inches, and having a twist of one turn in 7.29 inches.”

The rifle was tested against the Krag at 1,000 yards. Three five-shot groups for each rifle averaged 25.11 inches for the Krag and 13.72 inches for the Cole rifle (extreme spread). The next day, a 300-yard test was conducted with a different Krag with better results. Velocity tests for the Krag (at 53 feet) were 1,991.55 fps, and for the Cole, 2,058.66 fps. On July 23 and 26, three five-shot groups were fired at 1,000 yards. Results were 18.96 inches (Krag) and 17.46 inches (Cole.) The test on the 26th had the Krag set up with a different stock and fittings.

Results: 15.71 inches (Krag), 17.68 inches (Cole). On October 1, firings were done at 1,200 and 1,500 yards. At 1,200: 28.6 inches (Krag), 23.5 inches (Cole) and 23.1 inches (new model Springfield rifle 2,300 fps velocity). At 1,500 yards, the results were 40.3 inches (Krag), 37.0 inches (Cole) and 26.9 inches (Springfield).

At this point, the Board in charge of testing sought to conduct further tests to determine the effects of different twist rates and the type of rifling with “an exhaustive series of firings with a barrel rifled according to Dr. Cole’s plan.”

On June 14, 1902, the Board met to consider test results comparing a new Cole barrel with an 8-inch twist to the new Springfield barrel with 8-, 9- and 10-inch twists.

Through March and April, 80 five-shot groups were fired in the above three twist rates at 500 yards with a group average of 4.4 inches for the four-groove Springfield barrel. The same number was fired through a Cole barrel rifled with an 8-inch twist for a group average of 3.9 inches. 80 groups were shot through the Springfield at 500 yards from May through June using 8- and 9-inch twists for a group average of 4.07 inches. Through the same period, 72 groups were fired through the Cole, and the group average was 3.8 inches. From February through June, 46 groups were fired at 1,000 yards through the Springfield for a group average of 11.33 inches. Simultaneously, 38 groups were fired through the Cole for group averages of 10.33 inches. Pressure measurements for the Cole and Springfield rifles were virtually the same.

The Board recommended that Cole system barrels be made for the first 500 Springfield magazine rifles produced for field and armory testing.

By this time, Buffington, who had served as interim Chief of Ordnance, had been replaced by William Crozier. Crozier raised the issue that the superiority of Cole’s system may have resulted from gas escape in the four-groove barrel and recommended cupping the base of the bullet. Frankford Arsenal produced 3,000 rounds of this ammunition.

Beginning July 26, 1902, 20 barrels of each type were produced for further testing with a 1:10-inch twist. The results for 500-yard tests (one five-shot group per barrel) yielded an average of 5.6 inches for the Cole and 5.9 for the Springfield. At 1,000 yards, the results were 15.6 for the Cole and 22.3 for the Springfield. Considering the terrible results of the Springfield 1:10 twist, two additional barrels with a 1:8-inch twist were produced of each type. At 500 yards, the Cole averaged 4.6 inches and the Springfield 5.4 inches for five groups, and at 1,000 yards, the results were Cole 7.5 inches, Springfield, 10.0. In terms of velocity, at 1,000 yards, the Cole had an advantage.

At the request of Captain Lissak, the above two rifles were sent to the Seagirt, New Jersey range, where the National matches were being held. There, opportunities were offered to various and sundry to try them out. The reported results for 200, 600 and 1,000 yards rated both rifles equally accurate, with opinions favoring the Springfield rifling.

In its September 23, 1902, report, the Board recommended two other rifles be produced with the 1:8 twist, one with each type of rifling for analysis of accuracy plus endurance. To this end, the production of 10,000 cartridges was requested for a 5,000-round test for each rifle. The Board’s report garnered the following reply:

“OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF ORDNANCE

Washington, September 29, 1902

Respectfully returned to the commanding officer, Springfield Armory. The experiments with the elliptical-groove system (Cole’s) should be discontinued. Dr. Cole has been informed that the Department does not consider that it possesses sufficient advantages over present system to warrant further experiments.

William Crozier

Brigadier-General, Chief of Ordnance”

The Annual Report offers no further comments from Board members or any expert shooters at the Springfield Armory, including Freeman Bull and Richard Hare!

In the January 13, 1910 Arms and the Man (which predated American Rifleman), gun-designer Charles Newton excoriated the Crozier decision. “In conclusion we have failed to find any point in which the land and groove system is proven or even claimed to be superior to the oval bore in a smokeless-powder rifle and the latter is conclusively shown by the Ordnance Department’s experiments above cited to be more accurate and it will hardly be questioned that it is more durable, more easily cleaned and delivers its bullets in more perfect condition than the land-and-groove type.”

To this day, barrels of every U.S. military small arm have been rifled with the land and groove system.

The next phase in alternative rifling came in the late 1930s with the German application of hammer forging to barrel making. This method was first applied to the MG42 machine gun, where the barrel was hammered into shape over a mandrel placed in the bore of a barrel blank, shaping, rifling and chambering in one step. Hammer forging requires expensive machinery.

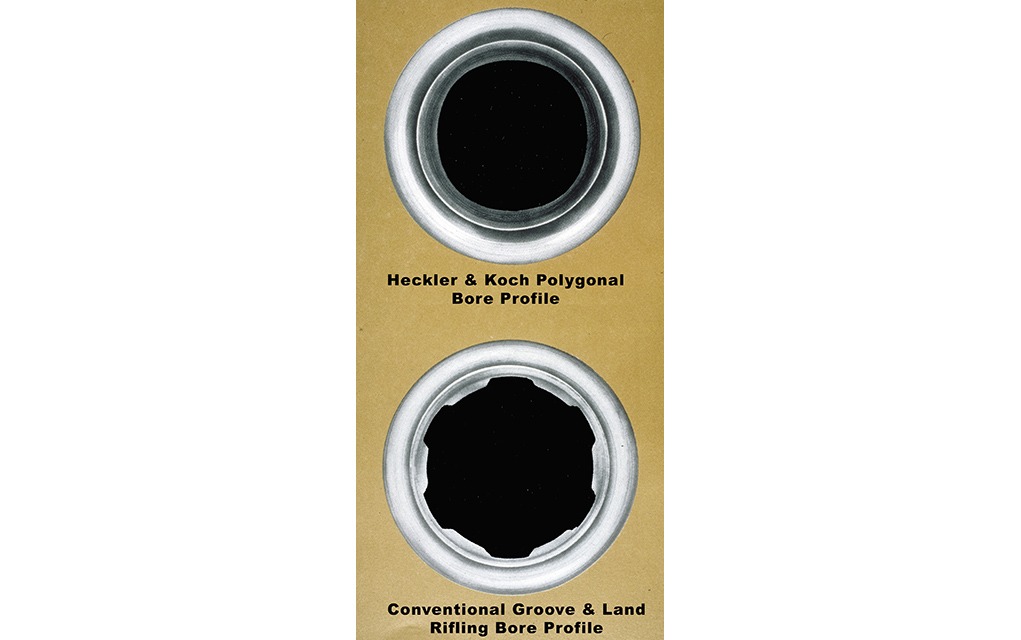

In the Post-War era, this technique is mainly used to produce what is now termed “polygonal rifling.” For clarity’s sake, the only actual polygonal rifling was that in Whitworth-pattern barrels with flat sides and angled corners. Current “polygonal” bores have sloping sides and rounded corners. This term also encompasses Metford rifling and oval boring.

In the 1960s, Heckler & Koch (HK) began marketing a line of rifles and handguns with polygonal rifling. While the details of HK’s testing are proprietary, its conclusion is as follows: “Compared to conventional land-and-groove profile barrels, bullets fired through polygonal barrels have a higher muzzle velocity, as there is little gas leakage. This increases the amount of energy acting on the base of the bullet. There is no chance of the propellant gases “overtaking” the bullet and adversely affecting its flight properties and directional stability.

A polygonal profiled barrel does not have any sharp internal edges. This virtually eliminates the deposit of residues. A polygonal barrel is easily cleaned, reflects heat more efficiently and has a high resistance to erosion. With no sharp edges as with land and groove barrels, the notching effect on bullets is also avoided. The net effect is increased barrel service life plus no need to finish machine the barrel or chrome plate it. Manufactured with HK’s famous cold hammer-forged barrel process, these polygonal barrels are made of HK proprietary cannon grade steel.”

Given the advantages of longer barrel life, virtually all current polygonal barrels are used on semi-automatic and automatic guns (both rifles and handguns), which see far more shooting than other actions.

Additional advantages of polygonal bores: they can be produced through buttoning and cutting. There is controversy over the use of lead-alloy bullets, particularly in semi-auto handguns where lead buildup just forward of the chamber can cause excessive pressures. Careful inspection and cleaning are the rule and heeding warnings issued by the manufacturer.

Currently, polygonal rifling is used by HK, CZ, Kahr, Glock, Magnum Research and Tanfoglio. The only American company to enter this market is La Rue Tactical, which produces high-end uppers for M-16 platform rifles and its own competition/sniper models.

Will polygonal rifling become the new standard? Significant changes may soon follow with the U.S. Army’s adoption of the HK M110A1 Squad Designated Marksman Rifle, Cal 7.62×51 (.308). A modified version, the G28 Compact Semi-Automatic Sniper System (CSASS), is the latest.

The reader may well wonder at the abrupt and apparently nonsensical decision to abandon oval boring on the part of William Crozier. The politics within the American military bureaucracy gives new meaning to the word “byzantine.” This dynamic is documented in the 1994 book Misfire: The History of How America’s Small Arms Have Failed Our Military by William H. Hallahan. Though this work has been criticized for specific technical errors, in terms of analyzing the personality quirks of those in charge of small arms development, it appears dead on.

A.R. Buffington was required to retire at age 64. Crozier (then a captain) was a popular and highly respected inventor in the Ordnance Department. His work on an improved Krag had little resemblance to the 96 Krag. Crozier was on good terms with Teddy Roosevelt and his Secretary of War, Elihu Root. When Root appointed Crozier Chief, the latter jumped over thirty officers his senior and rank to brigadier general. The old guard fought the appointment in Congress, but Root won in his shake-up of the military. Roosevelt and Root pressured Crozier to deliver a rifle equivalent to the Mausers Roosevelt had faced in Cuba.

It would seem understandable that Crozier had little interest in any modifications that might delay the delivery of the new rifle. The M-1903 Springfield was indeed an equivalent to the 98 Mauser. In fact, it bore enough similarities that the government paid Mauser $200,000 to avoid a patent-infringement lawsuit. Crozier later tangled with Isaac Newton Lewis over his machine gun. After a Senate investigation, Crozier was fired.

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt of Gun Digest 2023, 77th Edition.

Raise Your Firearms IQ:

Read the full article here