Rifle Cartridges That Never Made The Big Time

We take a look at some British and European rifle cartridges that were years ahead of their time but still failed to catch on.

It should not be news to any reader that the British and European gun trades were highly active in cartridge conceptualization and design from the advent of the 20th century to the outbreak of World War II. Cartridge designs rode a near-permanent wave during this period, but not all progressed beyond the experimental or proposition stage. This article is about a few of those obscure bolt-action cartridge concepts of which we are aware. There are many more that are not covered here and even more that have disappeared in the fog of time, about which we will probably never know anything. An entire book could be written about them.

If I were a man of means, I would, just for the hell of it, have built a collection of British-style rifles chambered for some of these “never” cartridges on modern Granite Mountain Arms (GMA) or Prechtl custom Mauser 98 actions.

The disappearance or destruction of many European cartridge records during WWII and the recent closure of the historic Birmingham Proof House in the United Kingdom, followed by the sale of its records to an undisclosed collector, makes original research near impossible. I therefore relied on whatever sources of existing research I could find, sometimes almost verbatim. Sources will be acknowledged as best as possible, and where I omitted recognition, it is accidental, not intentional.

.250 Cogswell & Harrington Super High Velocity

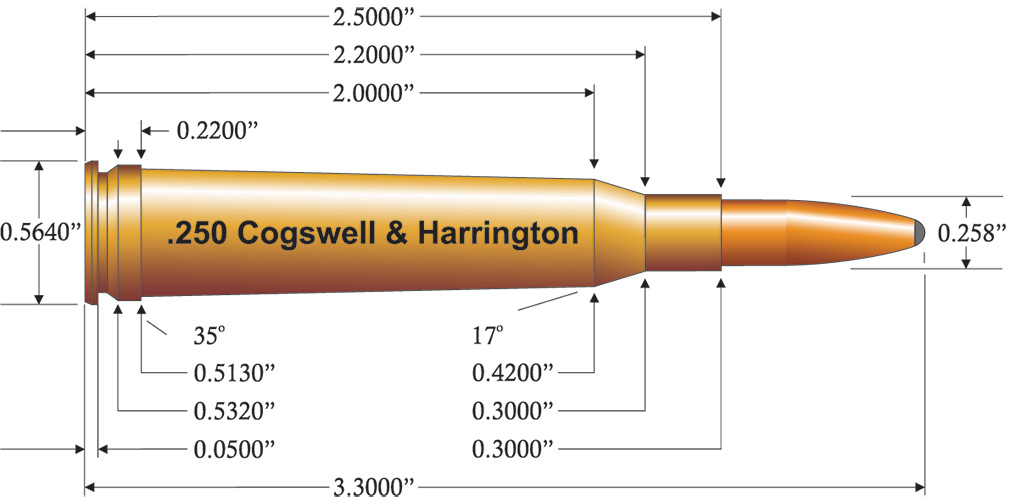

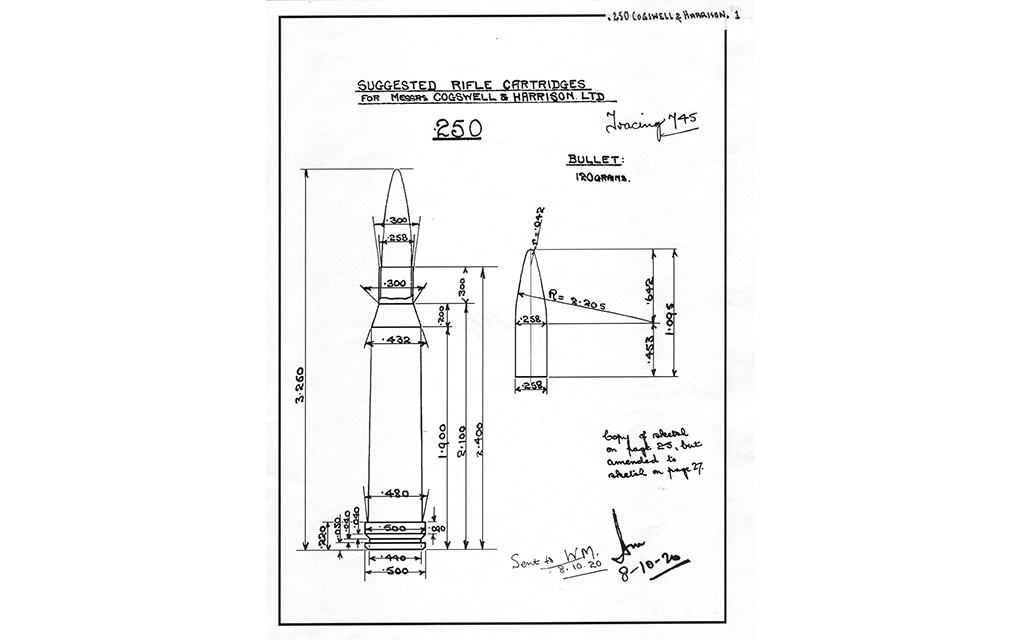

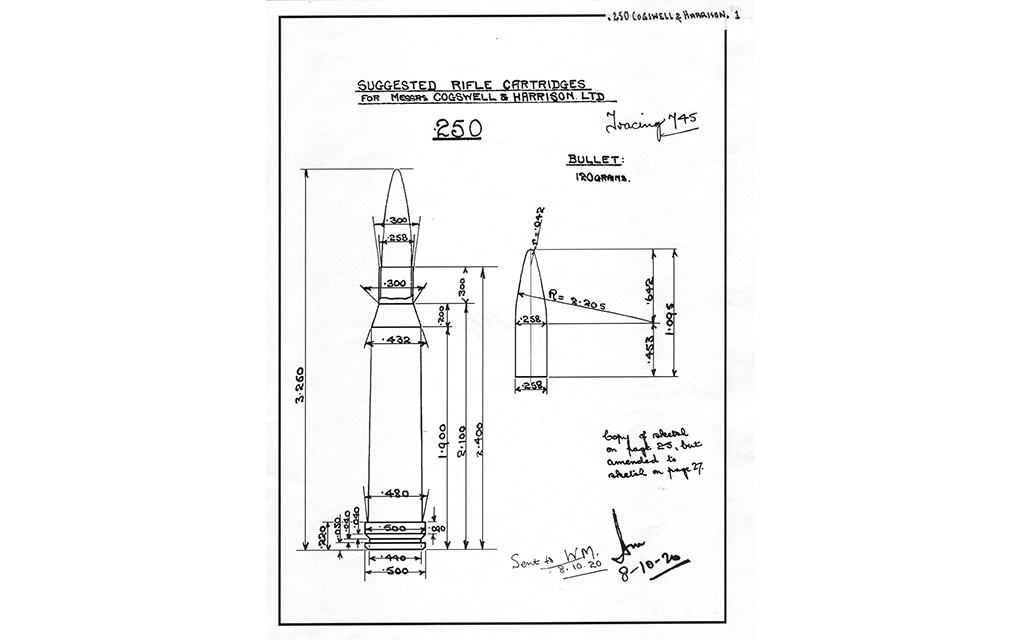

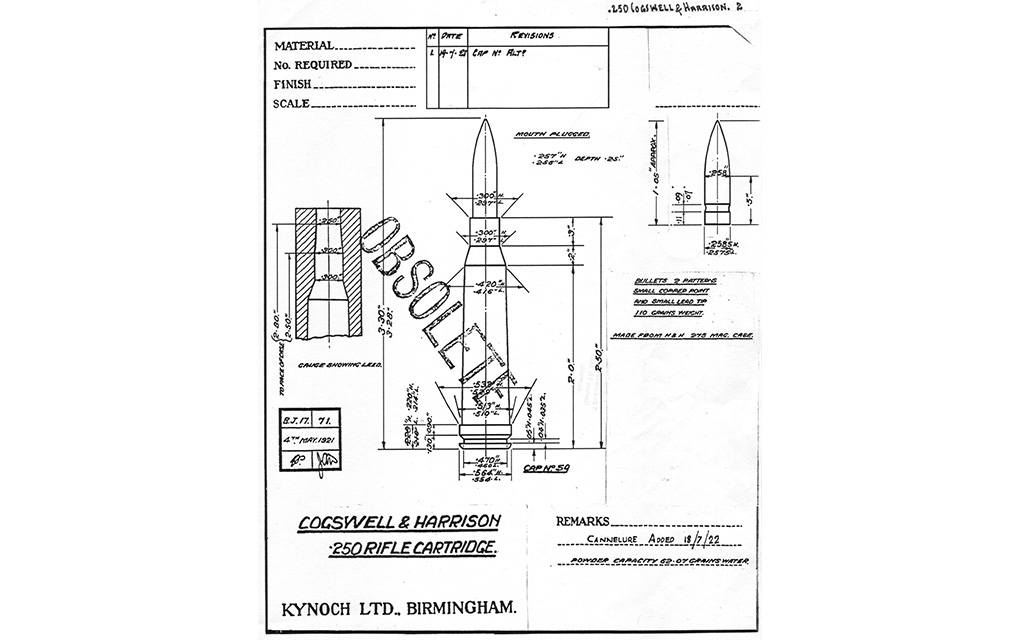

The .250 C&H cartridge was conceived around 1920. Two drawings exist: one from Eley dated October 8, 1920, and another from Kynoch (BJ17-71) of July 18, 1922. They differ materially. The cartridge color sketch image follows the Kynoch dimensions as it is the most recent, and even the 1920 sketch already notes modifications and refers to earlier drawings. Although I have never seen a .250 C&H cartridge, Fleming speculates that it may have seen limited production by Kynoch as the primer was revised in 1928.

The Eley drawing stipulates the case at 2.400 inches (60.96mm), while the Kynoch drawing lists it as 2.500 inches (63.5mm). The Eley drawing shows a maximum commercial cartridge length of 3.26 inches (82.80mm) and the Kynoch 3.30 inches (83.82mm). The bullet diameter is given as 0.258 inch (6.55mm) and not the present-day 0.257 inch (6.53mm). For all practical purposes, we can use the same barrel specifications as the .250-3000 Savage: a groove diameter of 0.257 inch (6.53mm) and a caliber of 0.250 inch (6.35mm).

The .250 Cogswell & Harrison design is typically British period-related, but the final version’s body taper was an excessive 2.991 degrees. The original drawing with the lesser body taper was the better of the two versions in my book, even with its odd belt diameter. Its neck measures 0.300 inch (7.62mm), constituting 120 percent of the caliber. The shoulder angle is a shallow, Cordite-charging-compatible 17 degrees. The case capacity is in the region of 62 to 65 grains of water.

It was superseded in 1923.

I could not find a definitive pressure specification for the .250 Cogswell & Harrison. QuickLoad lists it as 50,763 psi, but obviously without substantiation, and I have no idea where that specification was sourced. The .240 H&H Apex, which hails from the same year, has a maximum average pressure limit of 60,191 psi. The .250-3000 Savage of 1914, a lever-action cartridge, has a Sporting Arms & Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) maximum average pressure limit of 45,000 CUP (Copper Units Pressure), while the Commission internationale permanente pour l’épreuve des armes à feu portatives (CIP) limits it to 52,939 psi. Given that it is a post-WWI bolt-action cartridge design, I can see no reason the .250 Cogswell & Harrison cannot be loaded to .240 Apex levels. Thus, it compares to contemporary 0.257-inch rounds as detailed in the .250 C&H Performance Comparison Table.

.250 C&H Performance Comparison Table (26-inch barrel)

| Cartridge | Bullet (gr.) | MAP (psi) | Velocity (fps) |

| .257 Roberts | 120 | 58,000 | 2,800 |

| .25-’06 Remington | 120 | 63,000 | 3,100 |

| .250 Cogswell & Harrison | 120 | 55,000 | 3,125 |

| .257 Weatherby Magnum | 120 | 53,500 | 3,300 |

In practical terms, the .250 Cogswell & Harrington would have performed somewhere between the rimless .25-’06 Remington and the .257 Weatherby Magnum. It was hailed as an excellent option for “Hill-Shooting in India, or for Deer-Stalking in Scotland.”

.250 Cogswell & Harrington Drawing Differences

| Identification Date |

Rim Ø (R1) Diameter (in.) |

Belt Ø (R3) Diameter (in.) |

Base Ø (P1) Diameter (in.) |

Shoulder (P2) Diameter (in.) | Case (L3) Length (in.) | COAL (L6) (in.) |

| 1920 | .500 | .500 | .480 | .432 | 2.400 | 3.250 |

| 1923 (Kynoch) | .564 | .532 | .513 | .420 | 2.500 | 3.300 |

In the 1924 Cogswell & Harrison brochure, the cartridge was offered in a Mauser 98 action, and the Cordite ballistics listed it as 3,000 fps with a 110-grain bullet, which would have been achieved at pressures around 45,000 psi.

Drawings of two other belted Cogswell & Harrington cartridges also exist but have not been included here due to space restrictions; that of the .370 (Kynoch BJ17—71.4 dated May 5, 1921) and of a .380 (Eley 137.24 dated June 13, 1920) neither of which made it.

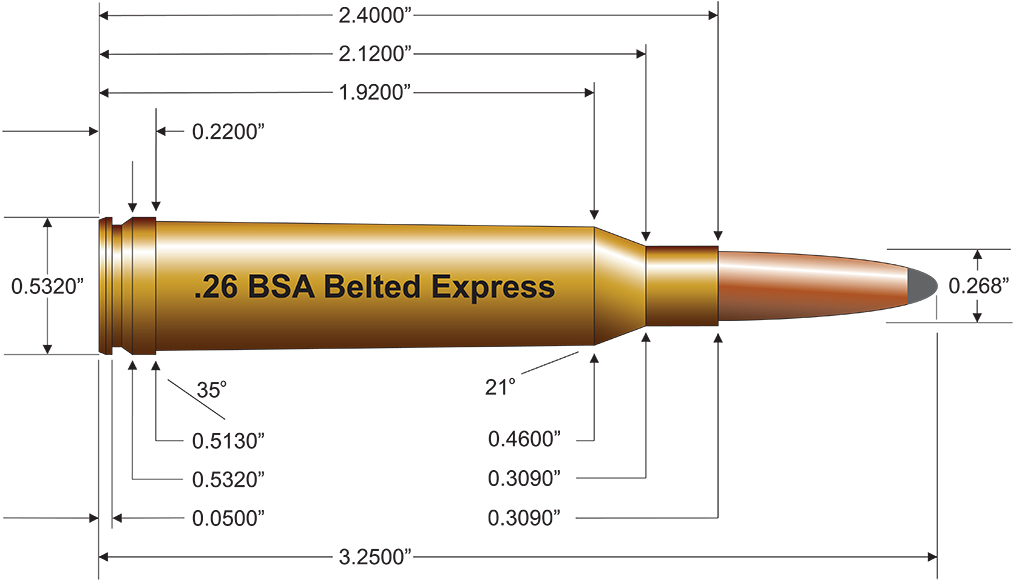

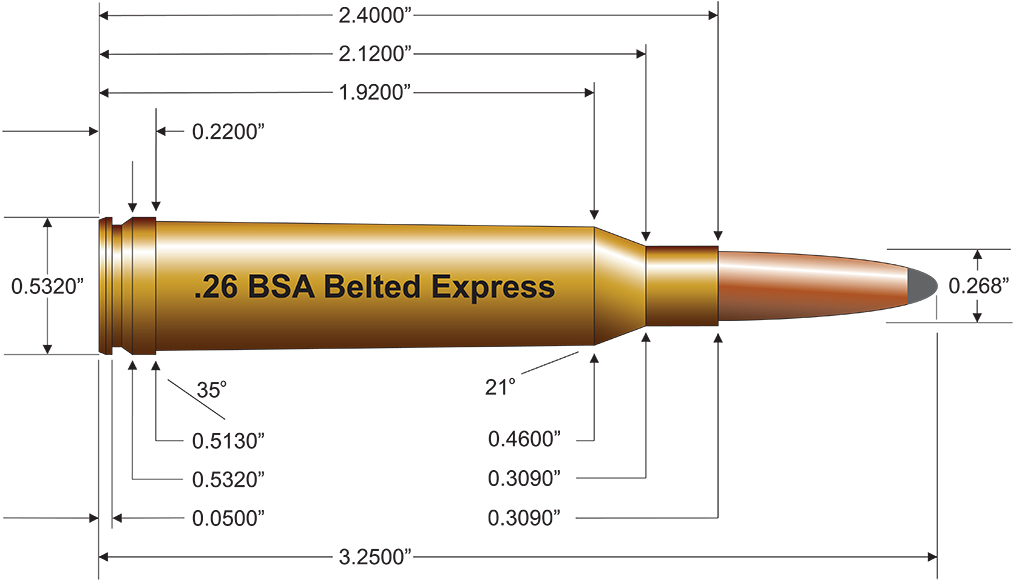

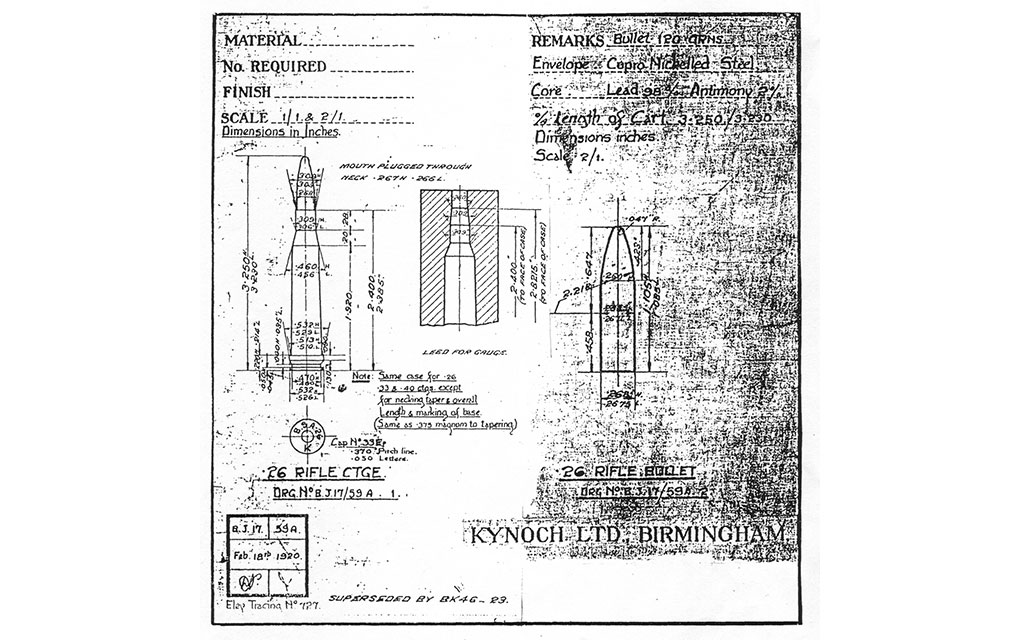

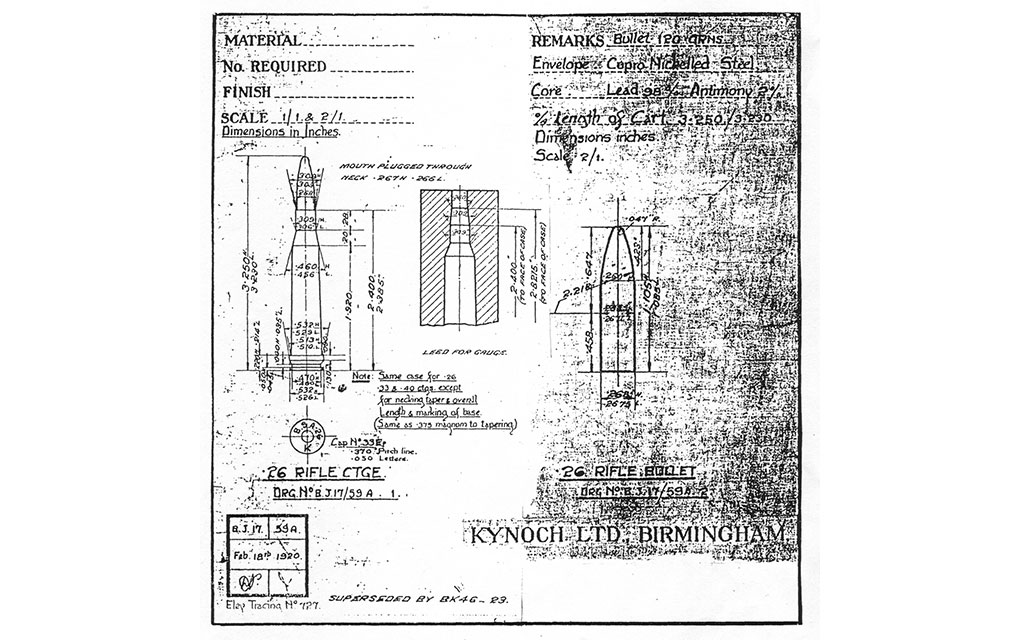

.26 BSA Rimless Belted Express

BSA (Birmingham Small Arms Company, Ltd.) was established around 1861. It played a significant role in British small arms manufacture until about 1973, when it closed. It offered airguns, rifles and cartridges of its own design, amongst which were the .26 and .40 BSA Rimless Belted Express. The earliest blueprint of the .26 BSA I have is Kynoch’s drawing numbered BJ17-55A, dated February 18, 1920. It was superseded by Kynoch drawing BK46-23, which I am still trying to find. At the time of the .26 BSA’s introduction, the company built its rifles on modified Enfield Pattern-14 bolt-action systems, not Mauser or Mannlicher actions common to other British gunmakers.

The .26 BSA Cartridge Comparison Table shows its closest ballistic rivals. The .264 Winchester Magnum could also have been included, but it is more powerful than the cartridges in the comparison. The .26 BSA’s rivals are the 6.5 Remington Magnum and the recent 6.5 PRC. That is quite a revelation, given that this cartridge is over a century old.

.26 BSA Cartridge Comparison Table (26-inch barrel)

| Cartridge | Year | Capacity (gr.) |

MAP (psi) |

Bullet (gr.) |

Velocity (fps) |

| .26 BSA | 1920 | 69.0 | 50,763 (QL) | 120 | 3,150 |

| .26 BSA | 1920 | 69.0 | 62,500 (CIP) | 120 | 3,250 |

| 6.5 Remington Mag. | 1966 | 68.0 | 63,901 | 120 | 3,000 |

| 6.5 PRC (Hornady) | 2018 | 68.0 | 65,000 | 120 | 3,250 |

Theoretically, the .26 BSA equals or marginally outperforms the highly touted 6.5 PRC cartridge if loaded to the same pressure levels. In practice, the 6.5 PRC is technically a much more sophisticated cartridge with better cartridge-to-chamber interface and combustion characteristics. (Not that the .260 BSA cartridge is the potentially better one; it already equaled the PRC’s ballistic potential a century ago.)

The .260 BSA has a 2.400-inch (60,96mm) long case with a 107.69 percent long neck, which conforms to contemporary criteria. The shallow shoulder angle of 21 degrees is high for a British cartridge. British rounds were loaded with Cordite strings as the propellant, which were inserted into the cases before the shoulder and neck were swaged into final shape during production. A shallow shoulder angle was consequently preferred as the most process-compatible. On the Kynoch drawing, the rim and belt diameters are the same as those of the .375 H&H Magnum and typical American belted cartridges.

The .26 BSA belt and the unnecessarily sharp tapered body (1.786 degrees) are not as efficient and enduring as the shorter body, sharper shoulder and lesser body taper of the contemporary 6.5 PRC and similar high-precision designs. Unless you are a handloader, those benefits do not necessarily manifest in ballistic or precision superiority. It also shows that Britain was at least 39 years ahead of the USA in terms of the 0.260-inch caliber cartridge design because the U.S. only introduced the belted .264 Winchester Magnum in 1959 and the 6.5mm Remington Magnum in 1966. The rimless 6.5 PRC wouldn’t see the light of day until 2018—98 years later!

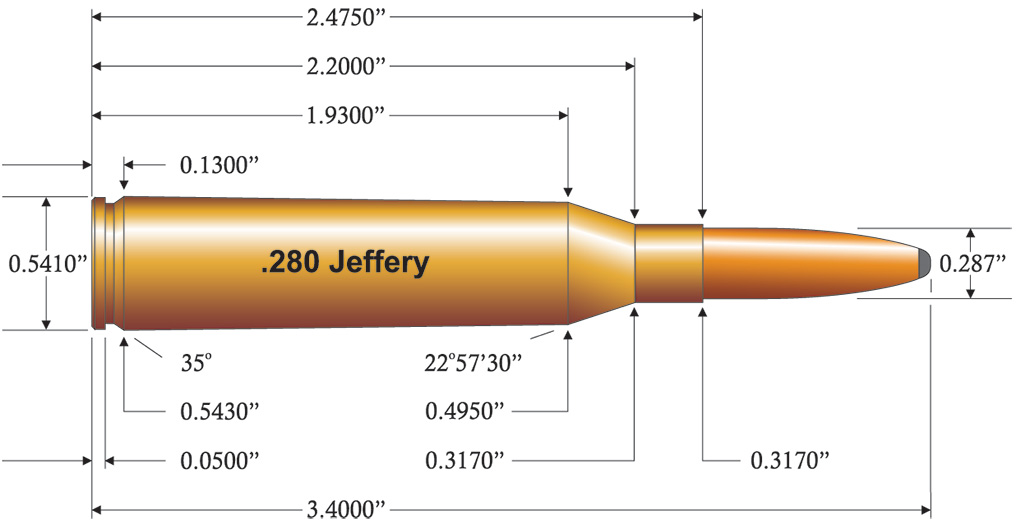

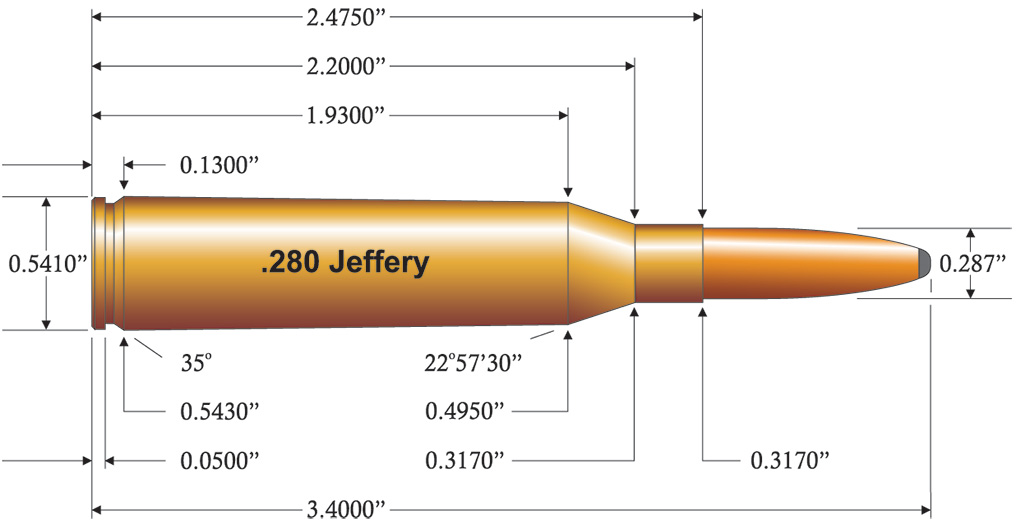

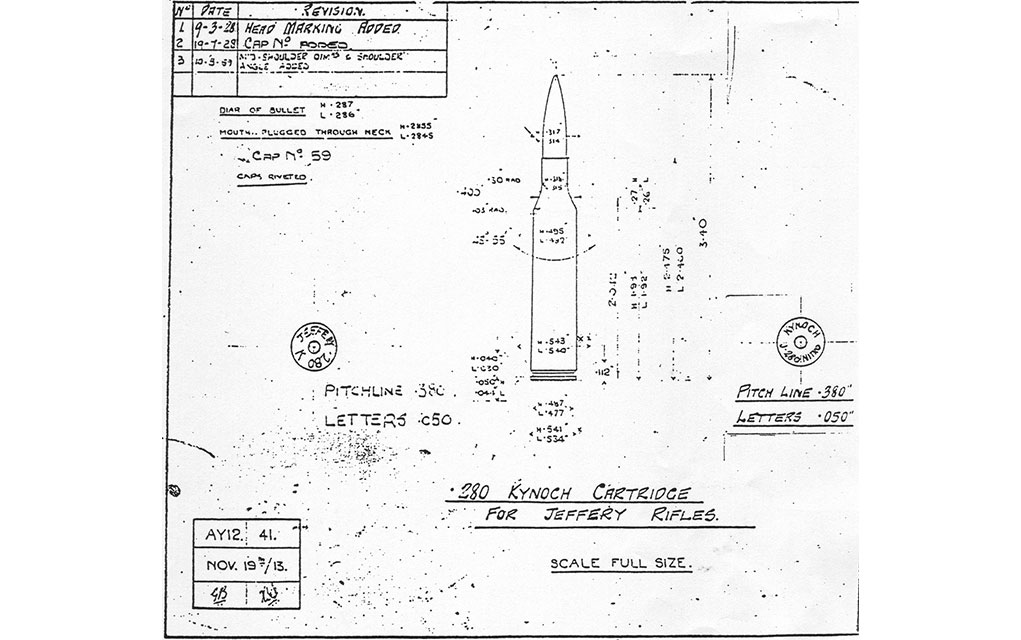

.280 Jeffery (.33/.280 Jeffery)

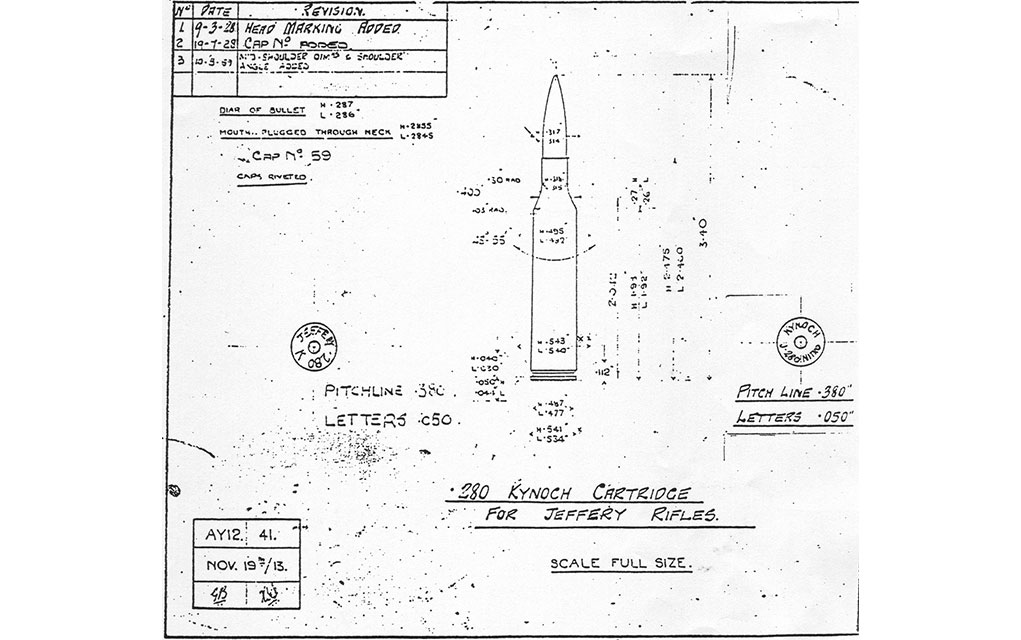

The .280 Jeffery originated with Kynoch drawing AY12-41 of November 19, 2013. It is a .333 Jeffery necked down to 0.287 inch (7.29mm), not the 0.284 inch (7.21mm) that later became the 7mm standard. W.J. Jeffery offered it in his Mauser 98 rifles. Most sources claim that it only went into production in 1915, but 1914 is more likely. As with the 7mm WSM and Remington’s UltraMag cartridges, its parent case was the .404 Jeffery, except the British took this approach 88 years before the Americans did. Loaded with 57 grains of Cordite, it launched a 140-grain bullet at 3,000 fps., Remember that the velocities listed for British cartridges were derived from 28-inch (711mm) proof barrels.

The .280 Jeffery is a forerunner of the modern 7mm Blaser Magnum, circa 2009. The Blaser, designed by my friend Christer Larsson, former head of ballistics at Norma Precision, has a marginally shorter case body (L1) and case length (L3) but less body taper and a sharper shoulder. These two cartridges have the same case water capacity and ballistics at identical pressure levels for all practical purposes.

Apart from bullet diameter, the minor dimensional differences are detailed in the accompanying .280 Jeffery Cartridge Comparison Table. Although the .280 was loaded hot in its day, modern propellants enable it to exceed original ballistics in 24-inch (610mm) barrels.

.280 Jeffery Cartridge Comparison Table (24-inch barrel)

| Cartridge | Bullet (gr.) | 90% MAP (psi) |

Capacity (gr.) |

Velocity (fps) |

| .280 (.33/.280) Jeffery | 140 | 54,825 | 82.5 | 3,350 |

| 7mm Blaser Magnum | 140 | 54,825 | 82.5 | 3,350 |

Loaded with modern propellants to contemporary pressure levels, the .280 Jeffery trades punches with the .280 Remington, 7x64mm Brenneke, 7mm WSM, 7mm Remington Magnum and the 7mm Blaser without ever taking to the canvas.

From a design perspective, its neck is a surprise for a British cartridge preceding WWI: It is short—around 98.2 percent of caliber. Even the .276 Enfield with which the British military experimented had a longer neck. The 22°57’30” shoulder was also rather sharp for a pre-WWI British round. The body taper is era-typical at a rather pronounced 1.687 degrees. It’s interesting that a cartridge would fall by the wayside, only to essentially be revived 96 years later as a solution to real or perceived needs. But that is the world of cartridges for you.

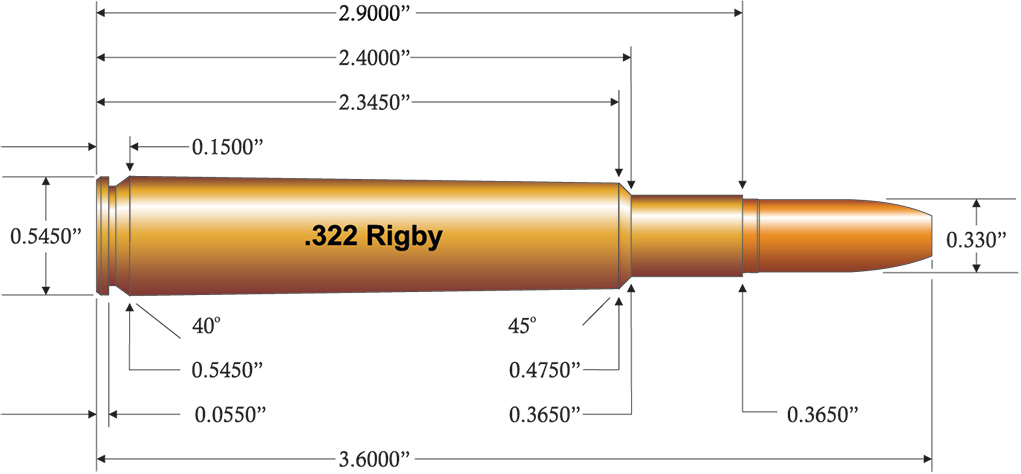

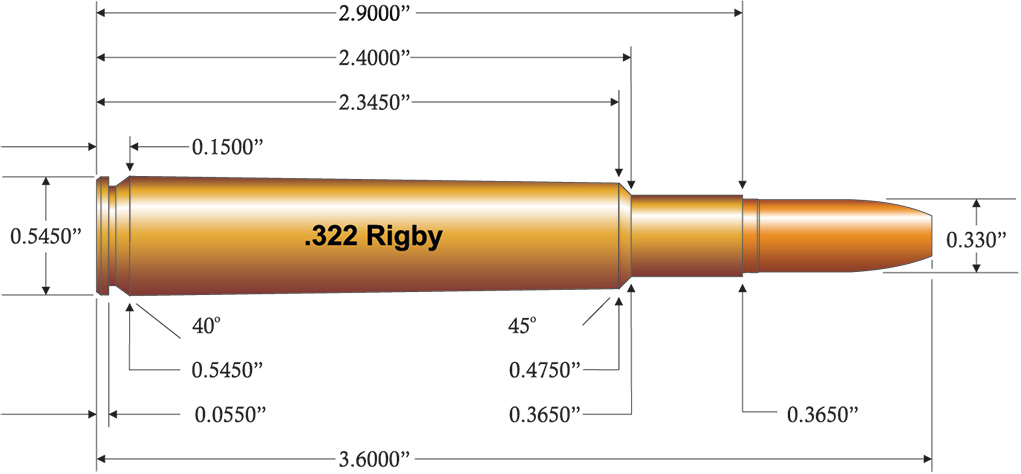

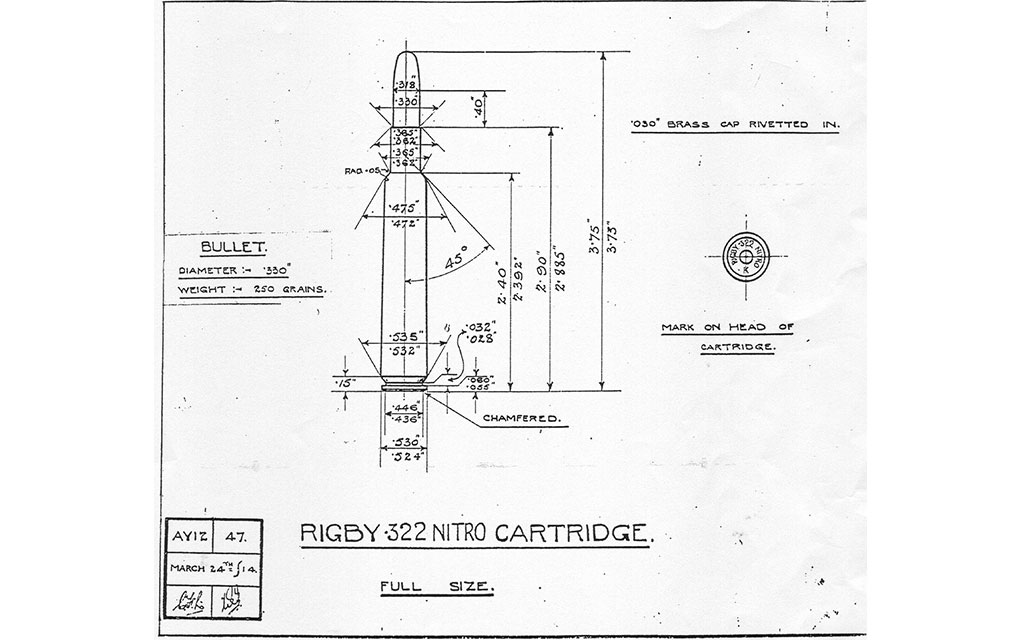

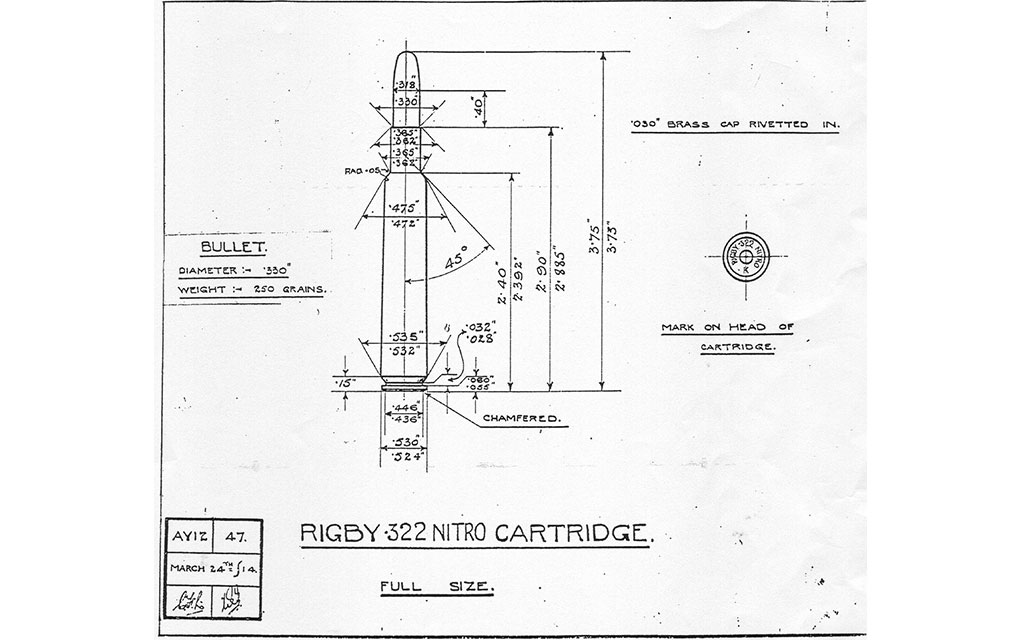

.322 Rigby Nitro

In the 1914 history section of the famous John Rigby & Co. website, there is a sentence that reads: “John Rigby had further plans for his .416 cartridge case. When World War I began in June 1914, he was working with Kynoch to develop the Rigby .322 Nitro cartridge. They intended to use a .330 diameter bullet weighing 250 grains. The velocity should have been about 3,000 feet per second, which would have produced more than 5,000 foot pounds of energy at the muzzle. Completion of the project was delayed until after the war, but with John Rigby’s death in 1916 all development ceased.”

The .322 Rigby died with its conceiver and was never commercially produced. A few cartridges must have been made for experimental purposes because there are a few specimens in collectors’ hands. The 250-grain 0.330-inch bullet made the .318 Westley Richards (circa 1910) famous. Many years ago, I wrote: “The .322 Rigby was not conceived as a .350 Rigby Magnum necked down, but an original design. The various sources list slightly differing dimensions for the cartridge, but performance levels hovered around 2,500 fps with 275-grain bullets from 24-inch (610mm) barrels.”

However, John Rigby used the .404 Jeffery case as the basis for the .322, not his .416 case. That is abundantly clear from the March 17, 1914, letter posted on the Rigby website and the Kynoch drawing AY12-47 dated March 24, 1914. It is understandable because, as I explained in African Dangerous Game Cartridges (p. 277), he indirectly contributed to the creation of the .404 Jeffery.

Drawing AY12-47 shows the cartridge as having the same cartridge overall length of 3.75 inches (95.25mm) as the .416 Rigby (Mauser magnum-length action) rather than the 3.53 inches (89.66mm) of the .404 Jeffery. The latter can be fitted into a standard-length Mauser action with a stretched magazine box, as is commonly done to accommodate the .375 H&H Magnum (COAL 3.6 inches). Interestingly, this drawing does not specify the case body length (L1), but Ken Howell determined it by using CAD software to “reverse engineer” the dimension as 2.345 inches (59.56mm). Body taper has thus been calculated as 1.566 degrees.

The case water capacity of the .322 Rigby Nitro is in the region of 102 to 103 grains. Rigby specified the muzzle velocity at 3,000 fps with a 250-grain bullet using Cordite. I can only presume that this performance was to be derived from the typical 28-inch (711mm) test barrels standard in the British trade. Using QuickLoad and a British-style Woodleigh 250-grain 0.330-inch bullet, I derived an approximate pressure level of 62,500 psi, which is way above what would have been acceptable in 1914. I submit that Rigby’s velocity expectation for the 250-grain bullet was optimistic.

If, however, I use a 275-grain bullet with a length of 1.34 inches (34mm), I can simulate 2,500 fps from a 24-inch (610mm) barrel at a mere 47,137 psi—identical to the pressure specification of the .416 Rigby.

The accompanying comparison table details the contemporary cartridges most comparable to the .322 Rigby Nitro. Since the .322’s modern adversaries are all loaded to maximum average pressures (MAP) exceeding 60,000 psi, I settled on the pressure level for the .322 Rigby for comparison in QuickLoad using a 24-inch (610mm) barrel. The average of five top-performing loads at 90 percent of maximum average pressure was used.

.322 Rigby Cartridge Comparison Table (26-inch barrel)

| Cartridge | Bullet (gr.) |

90% MAP (psi) |

Capacity (gr.) |

Velocity (fps) |

| .318 Westley Richards | 250 | 43,075 | 69.0 | 2,385 |

| .322 Rigby Nitro | 250 | 54,000 | 103.0 | 2,760 |

| .338 Norma Magnum | 250 | 57,436 | 105.5 | 2,864 |

| .338 Lapua Magnum | 250 | 54,824 | 118.0 | 2,864 |

| .338 Remington UltraMag | 250 | 57,435 | 110.0 | 2,807 |

QuickLoad is not gospel, but it provides a solid comparative base for calculation. The ‘wonder kid’ .338 Lapua and Norma Magnums were essentially conceived 99 years ago! Reinventing the wheel seems to be the current pastime.

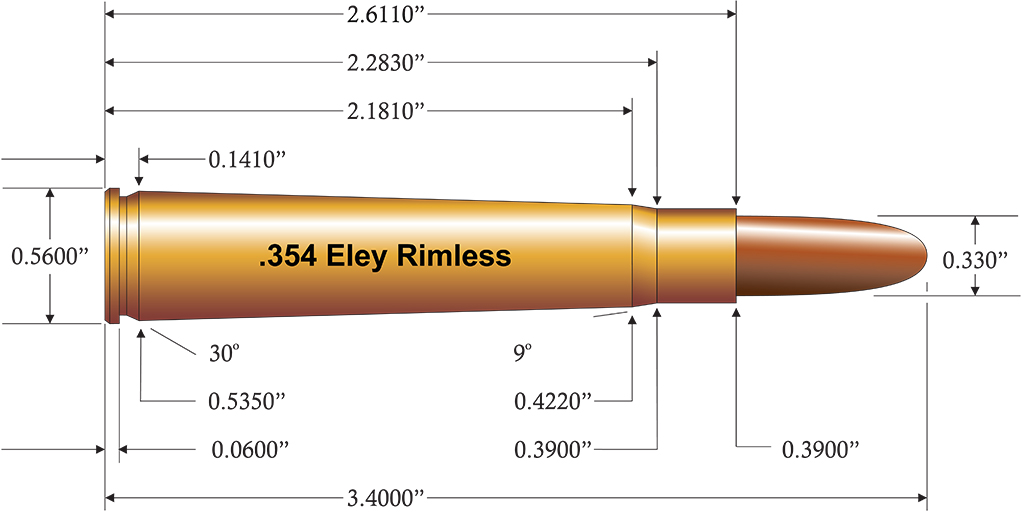

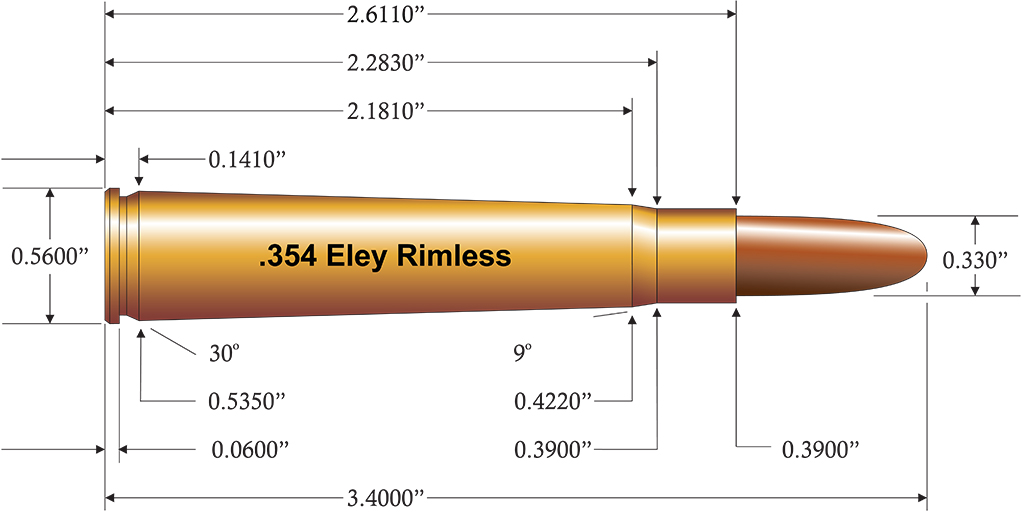

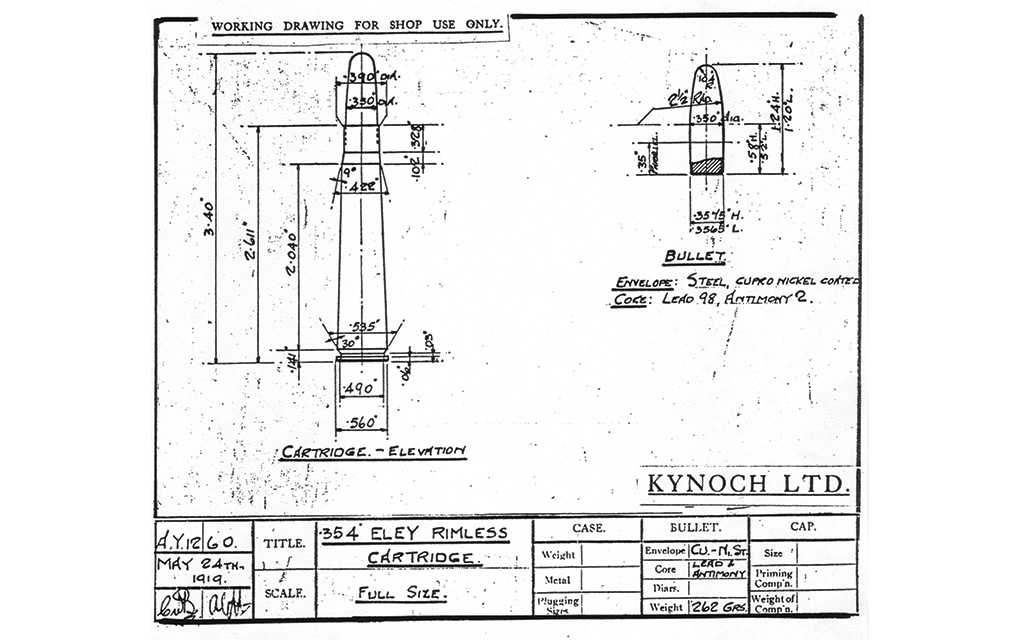

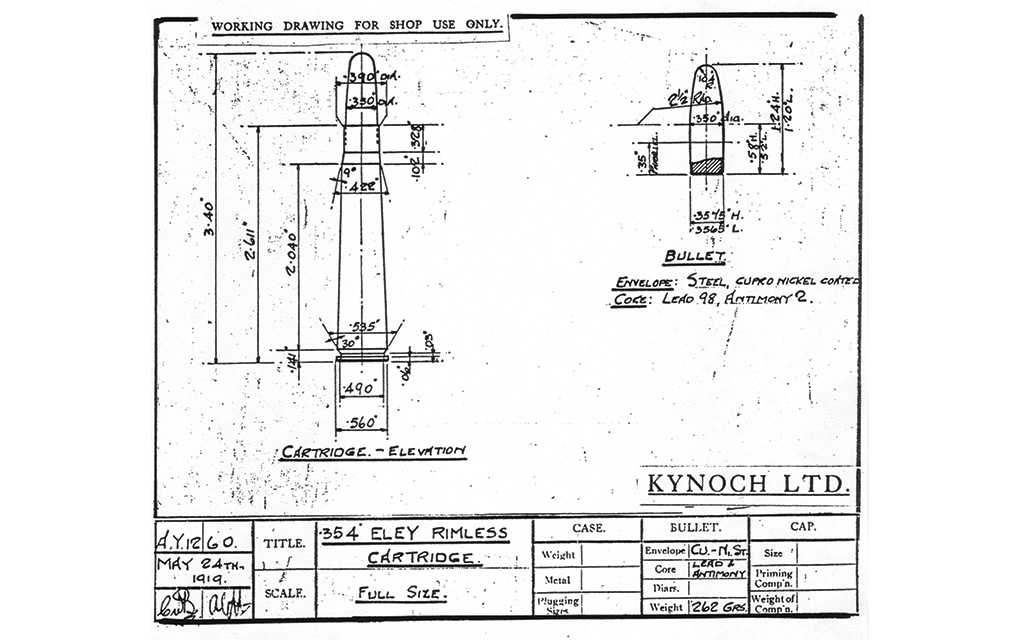

.354 Eley Rimless

The .354 Eley Rimless is a particularly obscure concept that never progressed beyond the drawing board. The drawing number, dY12-60, is especially odd. Even stranger is that it is a Kynoch drawing of an Eley cartridge marked “Working Drawing for Shop Use Only.” Its date is May 24, 1919, just more than six months after the end of WWI. I could not find any other reference to it except in Harding, but the timeframe Harding records raises more questions than answers.

He may be referring to yet another cartridge when he writes: “In 1906 Eley were to start the manufacture of cartridges for rifles designed by Sir Charles Ross, a Scotsman who had emigrated to Canada.” At least three variants were made by Eley, including two distinctly different versions of the .280-inch rimless, together with the rimless 0.354 inch. Alternatively, an Eley drawing, which I have not been privy to, dating back to 1906, may exist.

The 0.354-inch Eley essentially is a .280 Rimless Nitro Express Ross necked up. Both cartridges share the .404 Jeffery parent case with the rim (R1) and base (P1) measuring 0.535 inch (13.59mm) and a common shoulder (P2) of 0.422 inch (10.72mm). The shoulder angle of the .354 Eley is much shallower than that of the Ross, a meager 9 degrees rather than 26°33’63”, and it also reduces the body length (L1) by 0.141 inch (3.58mm) to a length of 2.040 inches (51.82mm). The water capacity of the .354 Eley case is in the region of 88 to 90 grains.

.354 Eley Cartridge Comparison Table (24-inch barrel)

| Cartridge | Bullet (gr.) | Pressure (psi) | Velocity (fps) |

| .354 Eley Rimless | 262 | 47,137 | 2,575 |

| .354 Eley Rimless | 262 | 57,435 | 2,710 |

| .358 Norma Magnum | 262 | 57,435 | 2,715 |

| 9,3x64mm Brenneke | 262 | 57,435 | 2,692 |

The .354 Eley’s bullet diameter would have been 0.350 inch (8.89mm) rather than the 0.358 inch (9.09mm) that eventually became popular. Body taper would have been excessive, as on the .280 Ross, around 3.405 degrees. Such a sharp body taper will make it prone to case-head separation when reloading the case repeatedly and inhibits case water capacity. With less body taper, the .354 Eley would easily have outperformed the .358 Norma Magnum and the 9.3x64mm Brenneke cartridges.

Assuming it was intended for the same straight-pull design as the .280 Ross, ballistic calculations were based on the identical maximum average pressure specification of 47,137 psi. For its projected ballistics, refer to the .354 Eley Cartridge Comparison Table. The bullet specified for the .354 Eley weighed 262 grains.

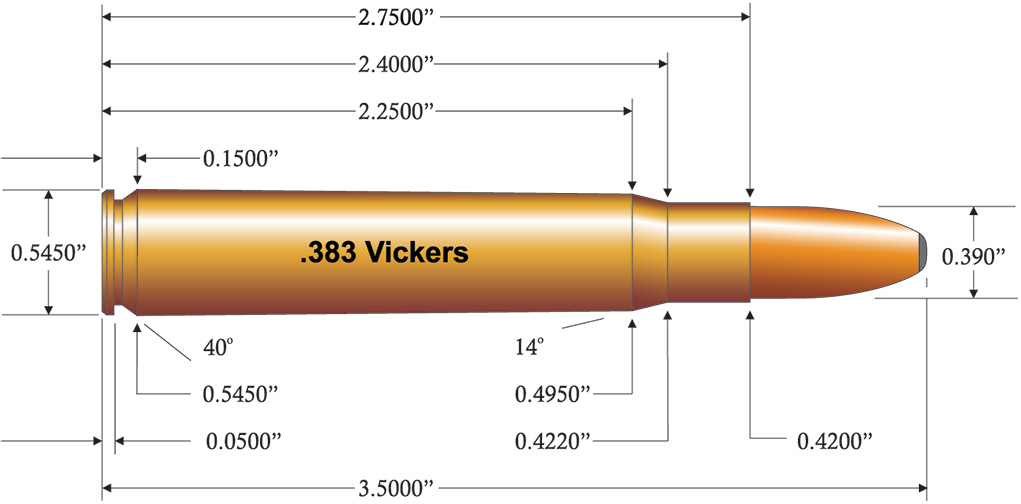

.383 Vickers

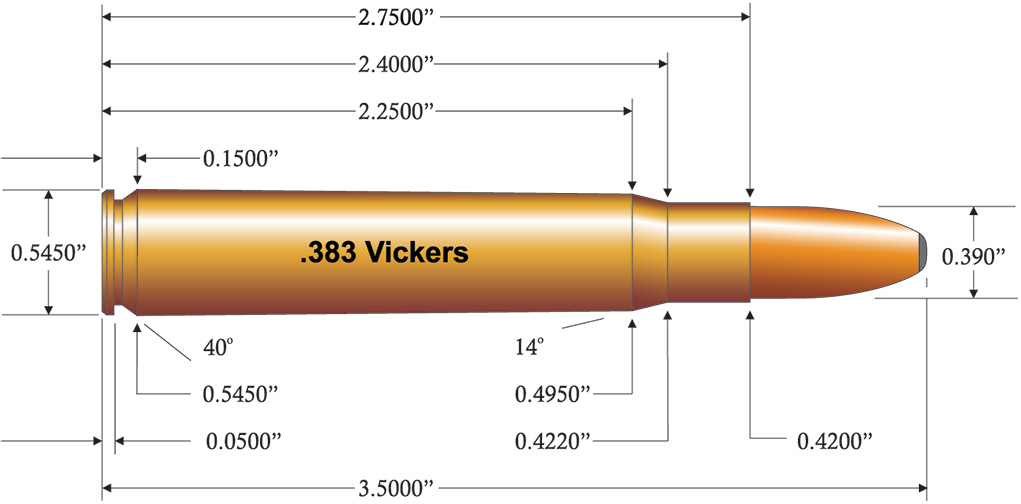

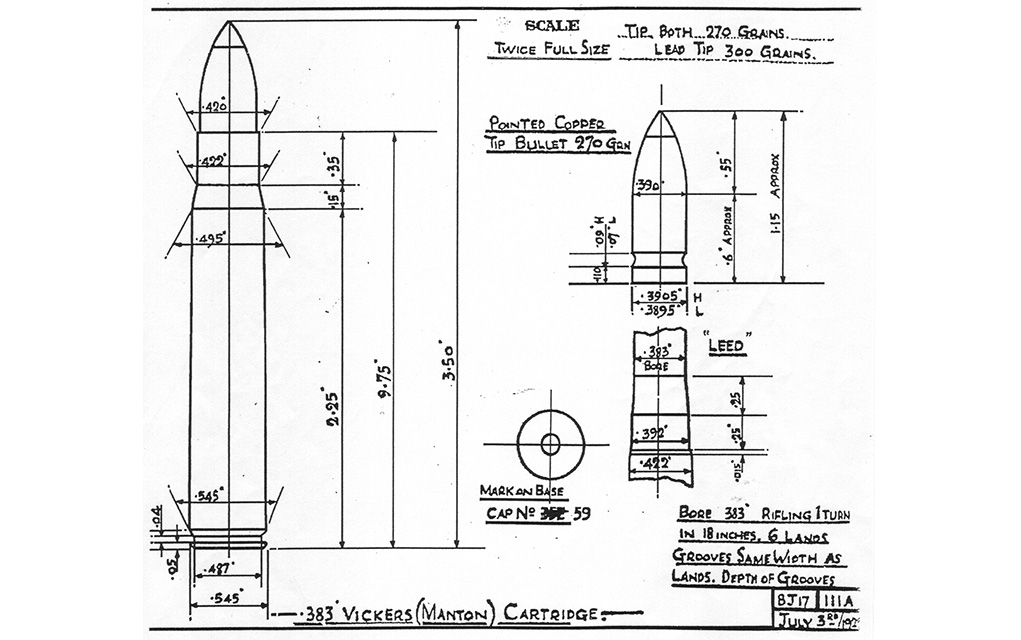

Who does not remember the images of the water-cooled Vickers machine gun hammering away at the German lines during WWI? Vickers Limited, which produced that machine gun, also created several cartridges. An exciting one that never saw the light of day was the .383 Vickers. Harding covers it as follows: “This is yet another experimental calibre produced by Kynoch Ltd, in 1927, presumably for Manton & Co. of Calcutta who must have rejected it, given their name is crossed out. To date I have yet to find a specimen of this calibre.”

If Bill Harding has not seen a specimen, none probably exist because he was the historian and archivist to the Birmingham Proof House (among many other related positions), and he has most probably seen it all.

According to the cartridge drawing BJ17-11A of July 3, 1929, the .383 Vickers would have been based on a slightly shortened (2.75 inches, 69.85mm) .404 Jeffery case given a 14-degree shallow angle and a short-for-the-era 91.38 percent of caliber neck. Bullets (270 and 300 grains) and groove diameters were to have been 0.390 inch (9.91mm), and the bore/caliber to measure 0.383 inch (9.73mm). The body taper was 1.35 degrees. The case water volume would have been around 103.5 grains.

This oddball caliber was most likely designed to compete with the .375 H&H Magnum, any bolt-action .40 prospects, and the venerable .450/400 in double rifles. The .400 H&H Rimless only came about 80 years later, but its groove diameter is 0.410 inch. I own both the .375 and .400 H&H cartridges, so I have a reasonable understanding of cartridges in the caliber bracket. To make a reasonable comparison, I used the SAAMI maximum average pressure specification of the .375 H&H Magnum of 62,000 psi (427 Mpa) as a baseline in the accompanying .383 Vickers Comparison Table from 24-inch (610mm) barrels.

.383 Vickers Comparison Table (300 grains)

| Cartridge | Bullet (gr.) | 90% MAP (psi) | Velocity (fps) |

| .375 H&H Magnum | 300 | 54,000 | 2,610 |

| .383 Vickers | 300 | 54,000 | 2,650 |

| .400 H&H Magnum | 300 | 54,000 | 2,775 |

The unusual bullet diameter could have been why Manton & Co. rejected the cartridge. It would have been a more capable design if Vickers had maintained the .404 Jeffery case length of 2.875 inches (73.02mm) and extended the cartridge length to equal that of the .375 H&H Magnum at 3.6 inches (91.44mm) and mated it to a .400–.410-inch bullet. Bear in mind that both the .404 Jeffery (1904) and the .416 Rigby (1911) had already established their reputations for the better part of 20 and 18 years, respectively. The .383 cartridge would not have brought anything new to the table.

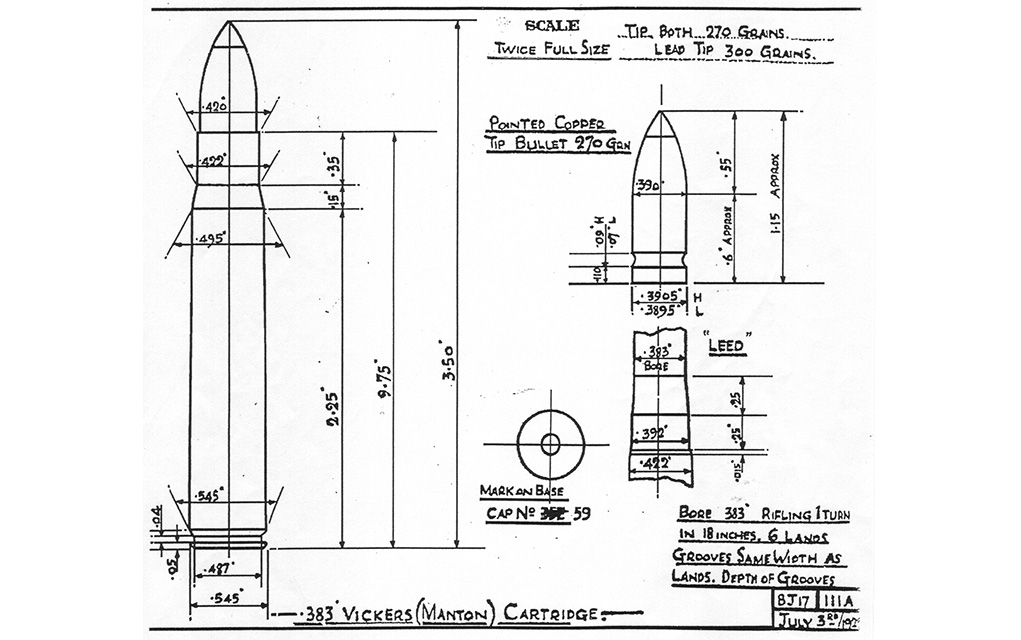

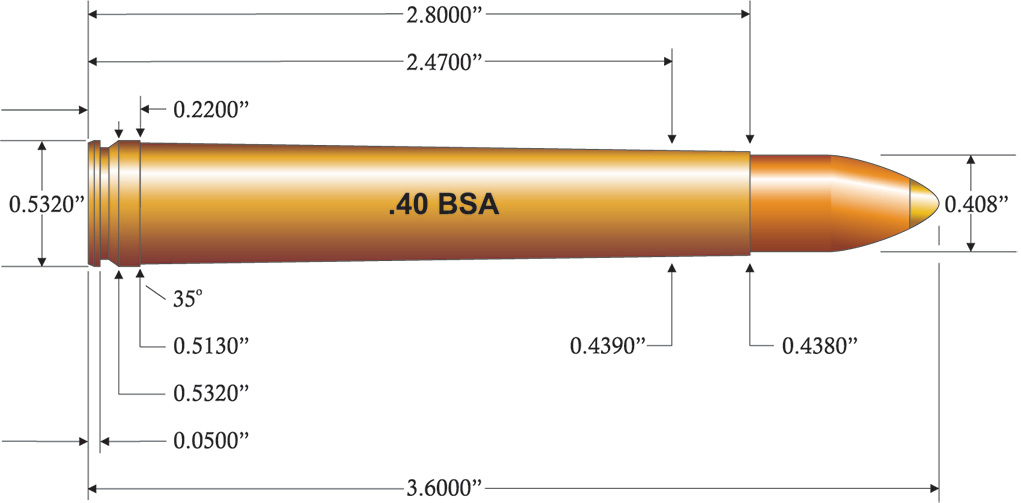

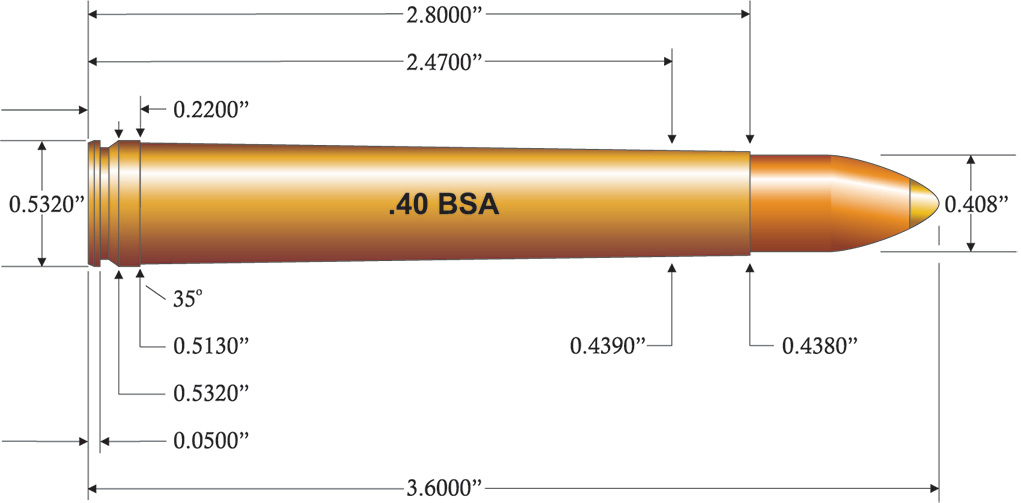

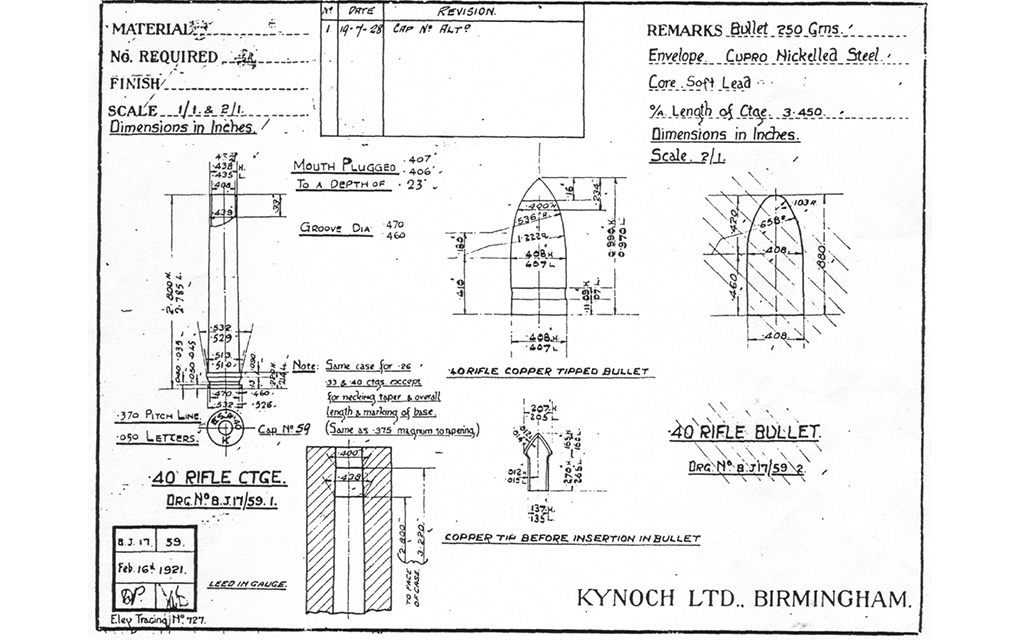

.40 BSA

Although the .41 Roper (designed by Sylvester Howard Roper, the American inventor of the motorcycle), was the first belted cartridge, Holland & Holland in the UK cemented the concept with its .400/375 H&H in 1905, which the great .375 H&H Magnum later superseded. [Editor’s note: In all my years of research, I had always understood the .400/375 H&H, or Velopex, to be the first belted cartridge. This shows that you never stop learning.]

In the world of double and top-break rifles, cartridges in the .400–.411-inch bracket have been very popular since about 1884. The .450/400 Nitro Express 3”, introduced by Jeffery in 1902, is still highly regarded in Africa. This popularity has never migrated to bolt-action rifles and cartridges, but it is not for lack of trying. In America, Charles Newton, Kleinguenther, Townsend Whelen and Art Alphin tried it and failed. British Sporting Arms (BSA) and Holland & Holland also tried and failed in the UK. It is just not a caliber that grips the imagination of the hunting public in the face of competition from the .375 H&H Magnum and the .416 Rigby.

BSA made one such UK attempt. Kynoch drawing BJ17-59, dated February 16, 1921, depicts the .40 BSA cartridge for which a light, copper-point .250-grain bullet of 0.408-inch (10.36mm) diameter was inexplicably specified. Bullets in the 400-grain class are preferred for cartridges in this performance bracket. The load was 69 grains of Cordite. It was a belted, stretched-length (2.8 inches, 71.12mm) straight-tapered wall cartridge geometrically comparable to the .458 Lott. BSA offered Enfield P14 rifles chambered for it.

.40 BSA Performance Table (24-inch barrel)

| Cartridge | Bullet (gr.) | 90% MAP (psi) | Capacity (gr.) | Velocity (fps) |

| .40 BSA | 260 | 57,435 | 104 | 2,925 |

| .40 BSA | 400 | 57,435 | 104 | 2,375 |

Had the .40 BSA survived, its closest modern rivals would have been the .400 H&H Belted Magnum of 2002 and the .400 Pondoro. The BSA and H&H’s case capacities are virtually identical, while the Pondoro has about 2 percent more capacity. Capacity differences are negligible.

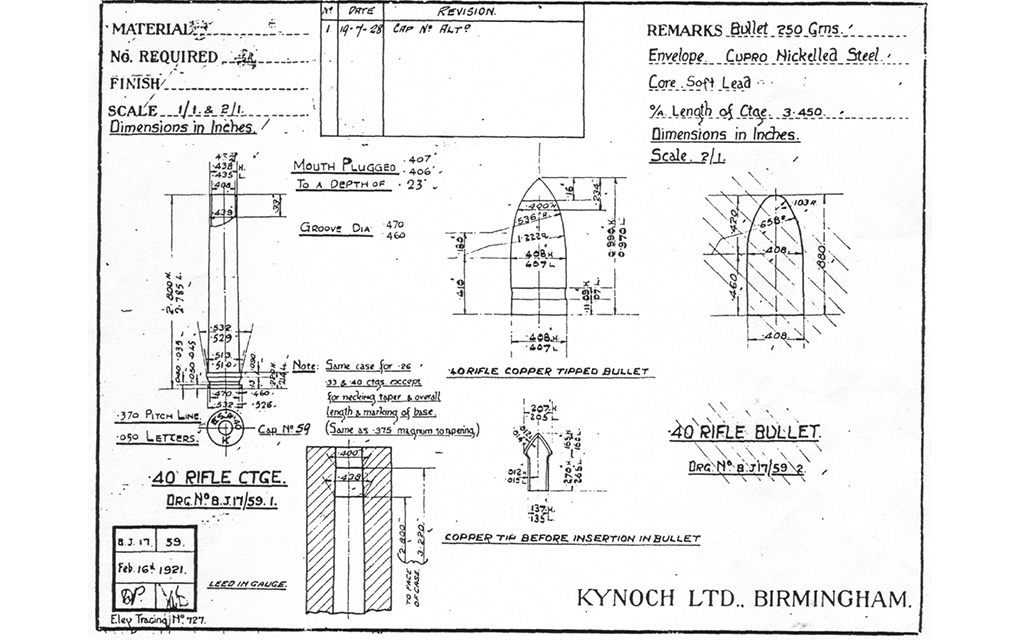

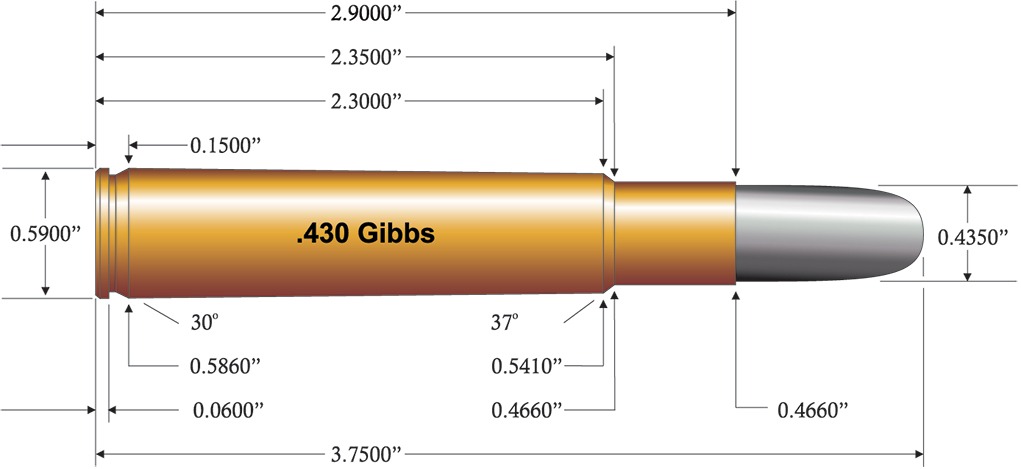

.430 Gibbs Nitro

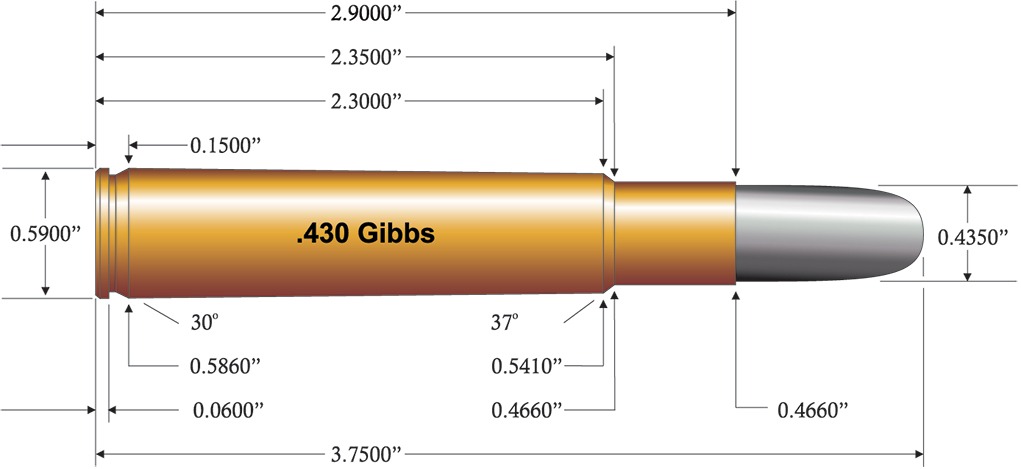

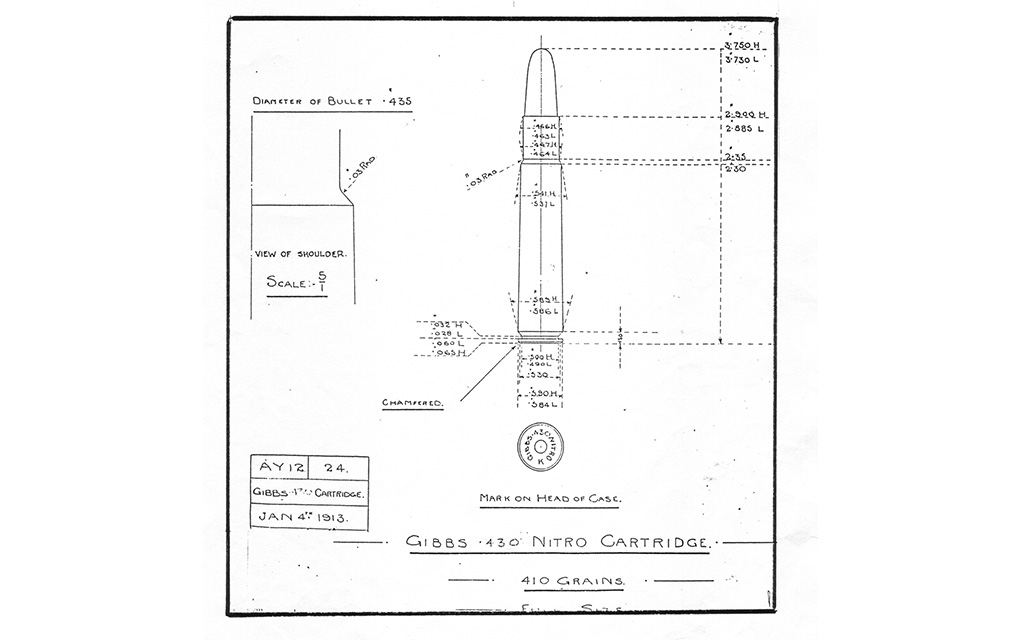

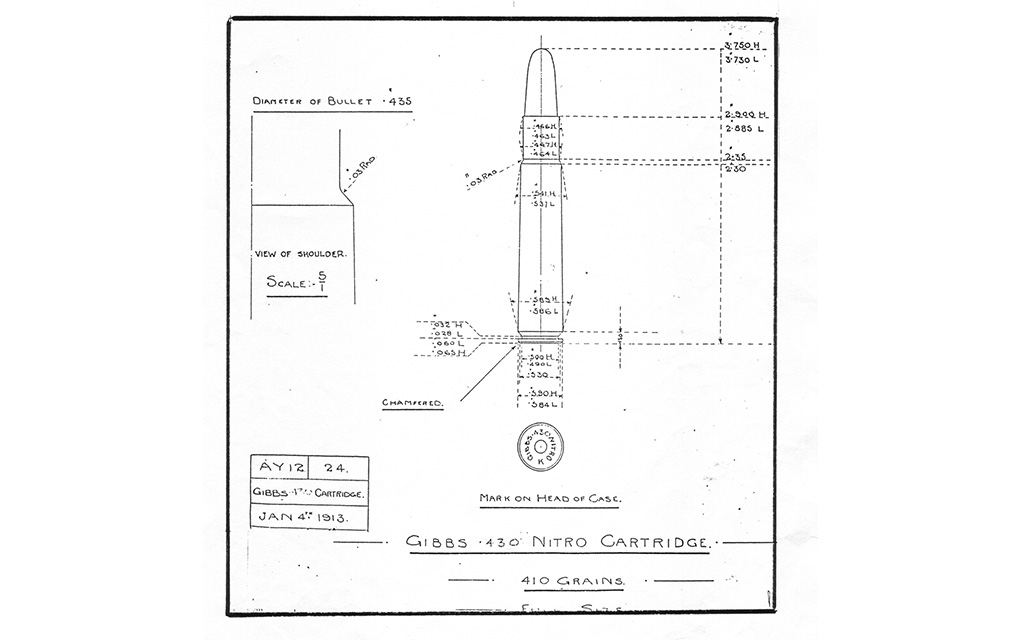

Although the .430 Gibbs Nitro, based on Kynoch drawing AY12-24 dated January 4, 1913, never went into production, a few specimens were specially created by my friend Otto Planyavski and are floating around collections. Planyavski even recreated the typical Gibbs .430 Nitro headstamp with the Kynoch K at the six o’clock position.

The .430 Gibbs Nitro was based on the full-length .416 Rigby case with a marginally shallower 37-degree shoulder and about 128 to 129 grains of water capacity. Its neck length is 129.4 percent of caliber, and its body taper is 1.2 degrees. The cartridge’s overall length (L6) was 3.750 inches (95.25mm). Therefore, the .430 Gibbs would have required a Mauser magnum-length action.

The Kynoch drawing specifies a 0.435-inch (11.05mm) bullet weighing 410 grains. Its bullet diameter is identical to that of the .425 Westley Richards. The .425 Westley Richards, introduced in 1909, uses a 347-grain 0.435-inch (11.05mm) bullet and is based on the .404 Jeffery case shortened and modified to a rebated rim configuration. Its case’s water capacity generally hovers in the region of 107 grains. The .430 Gibbs concept had obviously been intended to compete with the .416 Rigby, the .404 Jeffery, and the 11.2x72mm Schüler rather than the more compact and sedate .425 Westley Richards.

The case water capacity of the .430 Gibbs Nitro is almost identical to the brand-dependent average of the .416. Gibbs had specified a maximum average pressure of just 39,160 psi for its even bigger .505 Magnum Gibbs introduced in 1911. Given a difference of only two years between the introduction of the .416 Rigby and the .430 Gibbs and sharing the same case, it is reasonable to assume that the .430 Gibbs would have had a similar maximum average pressure specification to the .416 Rigby, namely 47,138 psi.

.430 Gibbs Nitro Comparison Table (410 grains, 24-inch barrel)

| Cartridge | Bullet (in.) | 95% MAP (psi) | Capacity (gr.) | Velocity (fps) |

| .416 Rigby | .416 | 44,781 | 127.5 | 2,425 |

| .404 Jeffery | .423 | 50,291 | 113.3 | 2,400 |

| .425 Westley Richards | .435 | 41,335 | 107.0 | 2,255 |

| .430 Gibbs Nitro | .435 | 44,781 | 128.2 | 2,480 |

| 11.2x7mm Schüler | .440 | 45,469 | 113.0 | 2,485 |

Using the .425 Westley Richards barrel specifications, the .430 Gibbs can be recreated in QuickLoad to approximate its ballistic potential. Due to the low pressures of the group of cartridges, 95 percent of the specified maximum average pressure was used for the QuickLoad calculations.

The .430 Gibbs Nitro would have been a formidable cartridge. However, the outbreak of WWI in 1914 and the likelihood that Rigby would not have considered parting with irreplaceable Magnum Mauser actions in hand during hostilities most likely scuttled the concept. Its only bullet diameter competitor would have been the less powerful .425 Westley Richards and the oddball Schüler, which never made it to the big time.

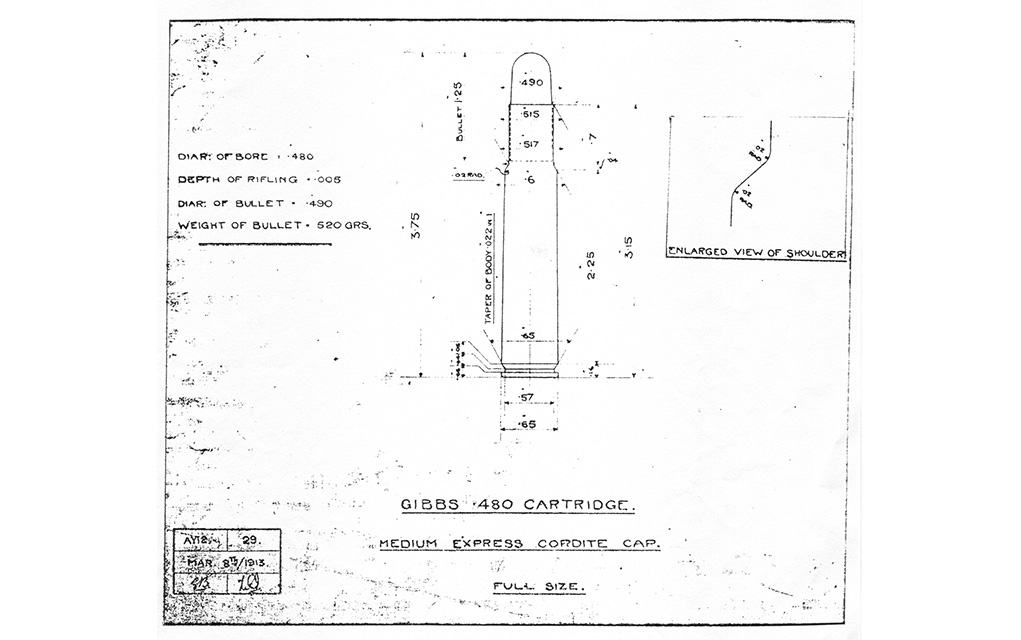

.480 Gibbs

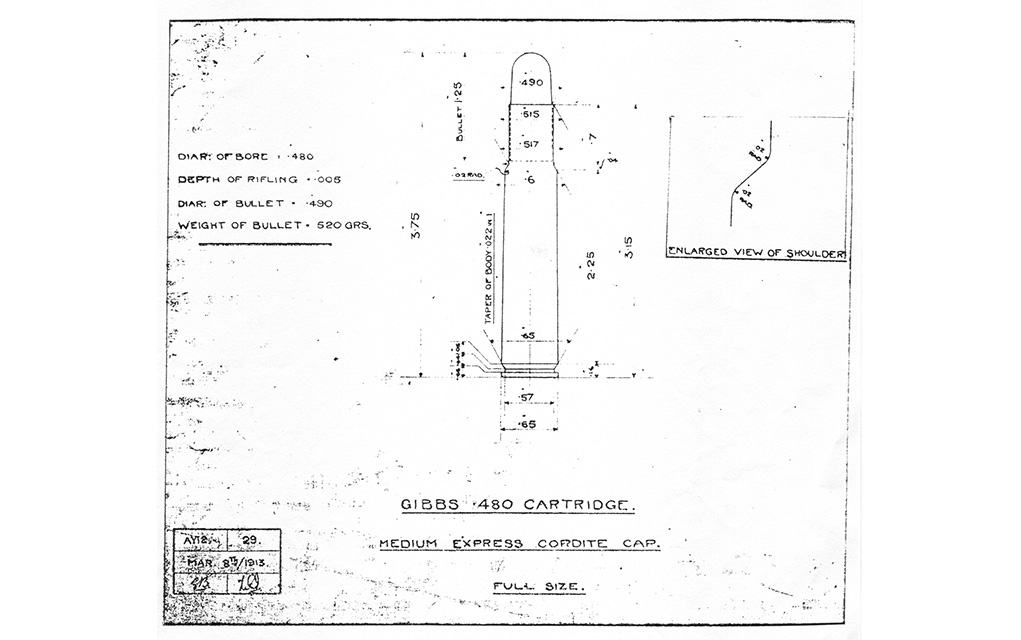

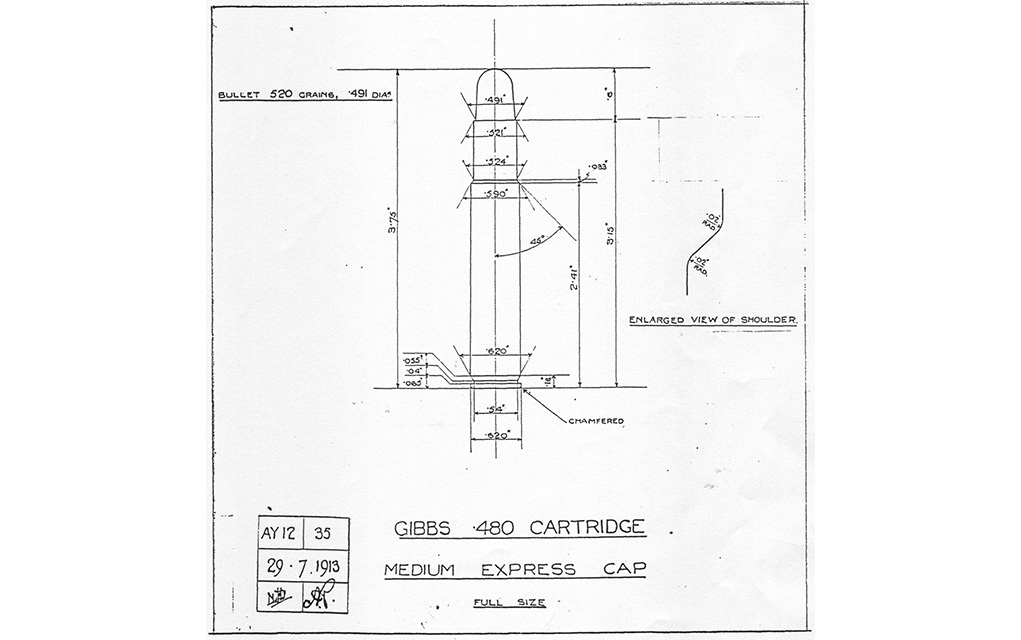

The .480 Gibbs was conceived shortly after the .430 Gibbs because the only drawing (Kynoch AY12-35) is dated July 29, 1913. Unlike the .430, it was based on Gibbs’ massive proprietary case, the .505 Magnum Gibbs. Both cartridges require a magnum-length Mauser action and magazine box. The .505 Magnum Gibbs cartridge succeeded and is even more popular in Africa than in its heyday. However, the .480 Gibbs never made it out of the starting blocks.

Although the .480 Gibbs may be considered a .505 Magnum Gibbs necked down to fire a 520-grain bullet of 0.491-inch (12.47mm) diameter, the .480’s case body length (L1) is 0.0498 inch (1.265mm) shorter. It shares the same 45-degree shoulder and case head configuration, but its body taper is .764 degrees, whereas the .505’s is between .988 and 1.002 degrees, depending on whether CIP or Birmingham Proof House dimensions are used. Its neck length is 144 percent of caliber.

.480 Gibbs Nitro Comparison Table

| Cartridge | Bullet (in.) |

87.5% MAP (psi) |

Capacity (gr.) |

Velocity (fps) |

| .480 Gibbs Nitro | 520 | 34,265 | 168.2 | 2,340 |

| .505 Magnum Gibbs | 525 | 34,265 | 178.4 | 2,300 |

| .500 Jeffery/12.7×70 Schüler | 535 | 41,879 | 154.2 | 2,450 |

The water capacity of the .480 Gibbs case would have been around 168.2 grains. For practical purposes, and in the absence of data, the maximum average pressure of the .480 should be identical to that of the .505 Gibbs: 39,160 psi.

We will never know why Gibbs considered a cartridge so close to his existing .505 Magnum Gibbs and used an odd bullet diameter. He probably realized it was a bad idea from a commercial perspective and abandoned the design. The closest rivals to the .480 Gibbs Nitro would have been the more compact .500 Jeffery and the in-house .505 Magnum Gibbs. The .480 Gibbs Nitro Comparison Table shows how these three would have stacked up against each other.

Summary

Countless other fascinating British and European cartridge designs never made it beyond the conceptual, experimental or limited-production phases. Books could be written about them. The golden thread that runs through them all is that almost everything lately introduced as innovative or pioneering is nothing but a rehash of these abandoned old cartridges.

The most significant advance in cartridges, in my view, is not the changes in dimensions that turn obsolete designs into the modern counterparts lately hailed as the be-all and end-all. It’s the American awakening to rim and base diameter dimensions for rounds above and beyond the .223 Remington, .30-’06 Springfield, and .300 Winchester Magnum that hampered American cartridges for a century. Now that the Americans have accepted the .404 Jeffery and .416 Rigby as parent cases and introduced the rimless .375 Ruger base and head geometry, a new world has opened up for cartridge design. Weatherby also recently contributed by stretching the .284 Winchester case. The only outstanding awakening still required for America is the 8x68mmS case head, once pursued by Charles Newton.

Author’s Note: I must thank and acknowledge the assistance of my friends Casey Lewis, Will Reuter, Paul Strydom and Nico Swart with material for this article.

Endnotes:

- 1. Fleming, Bill. British Sporting Rifle Cartridges. Armory Publications, 1993. Oceanside, USA

- 2. Fleming, Bill. British Sporting Rifle Cartridges. Armory Publications, 1993. Oceanside, USA

- 3. Ibid

- 4. Cogswell & Harrison catalog, 1924. Middlesex, UK

- 5. Barnes, Frank. Cartridges of the World 11th Ed. Gun Digest Books, 2006. Iola, USA

- 6. Hoyem, George. The History & Development of Small Arms Ammunition Vol III. Armory Publications, 2005. Missoula, USA

- 7. Van der Walt, Pierre. African Medium Game Cartridges. Pathfinder, 2018. Randburg, RSA.

- 8. Howell, Ken. Designing and Forming Custom Cartridges. The ICA, 1995. Stevensville, USA.

- 9. Harding, CW. Eley Cartridges. Quiller Publishing, 2009. Shrewsbury, UK.

- 10. Van der Walt, Pierre. African Dangerous Game Cartridges. Pathfinder, 2011. Randburg, RSA.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the May 2025 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More On Rifle Cartridges:

Read the full article here