Rifles: Transition Time

Transitions are regular features in life. Most of the major ones—like becoming a parent, changing careers or moving across state lines—are seen far enough in advance that ample preparation can take place ahead of the change. When it comes to shooting, transitioning usually refers to the process of bringing a backup gun into operation, during an active shooting event, after the primary firearm suddenly stops working. This tends to happen at less-than-opportune times and requires a different type of transition prep.

Traditionally, this skill has been mostly associated with professionals who are armed with duty carbines and sidearms, such as law enforcement tactical teams, military special operators and high-threat security details. Unfortunately, traditional times seem to be growing smaller in the rearview mirror. Home defense and EDC guns are still the most commonly used defensive tools, but the unstable world around us presents a few scenarios where having both a rifle and pistol is a good idea.

The need for a rapid transition usually involves a rifle that runs dry or malfunctions while threats are still active and within handgun range. When performed efficiently, this is faster than reloading or clearing the main firearm’s malfunction. As with other martial skills, failing to adequately prepare for transitioning under stress can have lethal results.

During my Army SOF years, most of my overt work required some form of rifle in hand and at least one pistol on my body. Transition work between the two guns was one of many drills worked into regular training, to the point of being second nature—when appropriate. That last part is important, because transitioning is not automatically the best option.

For example, my rifle once malfunctioned while I was fighting my way out of a well-planned, far ambush. Our attackers were several hundred meters away, on high ground and across an open river valley. I was in my pistol-shooting prime in those days, but robotically going for my backup would have been pretty silly. The sensible choice was to find cover and get my scoped rifle back into action, which I accomplished in short order.

Conversely, while engaging in urban close-quarters battle, there were many times I had to rapidly transition to my handgun in order to climb something, fight through an obstacle or clear a tight space where a shouldered rifle would have been a liability. There was never time to contemplate the process or untangle gear; those transitions had to happen on the fly. That’s all the more important on the homefront, where we’re unlikely to have the luxury of being backed up by armed teammates.

When carrying a rifle, there are three principal ways to clear a path for rapidly drawing and presenting a sidearm. The least preferred method is to simply drop the rifle to the ground. If that’s your only choice for getting to your backup firearm, so be it. But, as a general rule, relinquishing control of a firearm in the presence of active threats is a bad idea.

The need for a rapid transition usually involves a rifle that runs dry or malfunctions while threats are still active and within handgun range.

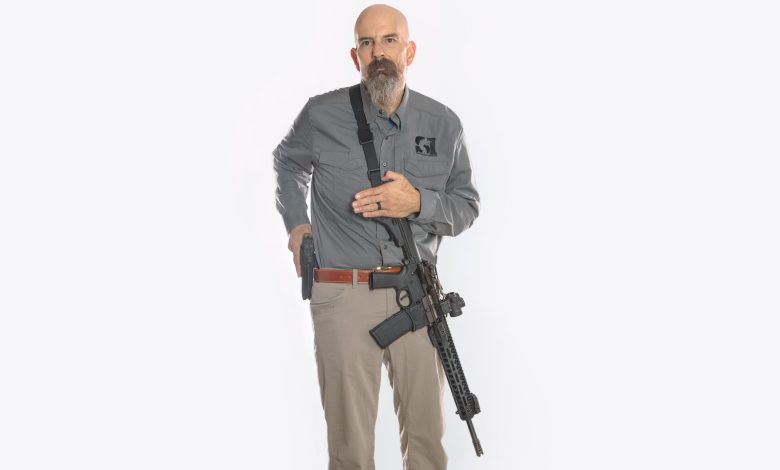

The second approach is to hold the rifle in your support hand, then draw and operate the backup gun with only the dominant hand. Again, if you have no other way to keep control of the rifle, this is probably your best choice—especially for a near and immediate threat. But in my experience, the most effective transition method is to simply let go of a rifle that has been slung across one’s chest, allowing the drawing and presenting of a hand-gun with a two-handed grip, while retaining control of the rifle.

There are nearly as many ways to wear a slung rifle as there are types of slings, but one method is tailor-made for this technique. Wearing it in “ready” or “assault” mode, with the rifle across the chest and muzzle low, makes transitioning easy. To achieve this, a two-point sling should be attached so that the rifle’s support-hand side lies flat against the body.

Further, the rear of the sling should pass over the strong-side shoulder, while the front is routed under the support-side armpit. This configuration allows one to simply drop the rifle so that it falls against the chest with the barrel angled down and the muzzle clear of legs and feet. Because this keeps the stock high on the strong side, a belt-holstered sidearm can be drawn normally.

If your backup is worn in front, the support hand can rotate the rifle around to the weak side to clear the midline for near-simultaneous drawing with the dominant hand. Some people find that moving the rifle around to the side also makes it easier to use a normal, two-handed grip for their sidearm. However, simply letting the rifle drop free allows one to focus solely on getting the backup into action quickly. You can always adjust the slung rifle’s position once you’ve dealt with the immediate threat.

People who are opposite-handed with their rifles and pistols may need to modify the sling’s routing to avoid having their sidearm get hung up during the draw stroke. To prevent this, the sling can be routed only around the back of the neck, passing over both shoulders. Upon releasing the rifle, it should still hang down, keeping either hip clear for the draw. A single-point sling will achieve the same orientation, but presents more challenges when moving or getting low to the ground without having positive control of the rifle.

Firearm transitions aren’t particularly tricky, but they still require practice. You can work the bugs out of your gear setup and technique while doing dry runs in the comfort of home. Interspersing a few live transitions in place of automatically reloading your long gun during range training will help you fine-tune the process and, ultimately, give you one less thing to worry about should your rifle stop working at the absolute worst possible time.

Read the full article here