Soldier sacrificed to save troops from being buried alive in WWII

The Villa Verde Trail, a 27-mile path in northern Luzon, Manila, was a narrow, densely vegetated mountain path. Deeply entrenched along this trail was elements of Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita’s Shobu fighting force — 8,000 well-trained, disciplined and fanatical soldiers of within the Japanese army.

The trail intersected Highway 5, a major Japanese highway and supply route. To eliminate the Japanese from Villa Verde would help to secure one of the few routes to the Cagayan Valley in Luzon.

Gen. Walter Krueger, commander of the Sixth Army, knew the task would be no easy feat.

“The enemy had made good use of the terrain which, with its sharp ridges and deep ravines, was ideally adapted for defense. He had dug innumerable caves, had provided defense positions on the reverse slopes of the ridges and had established excellent observation stations that permitted him to use his artillery to best advantage,” Gen. Krueger noted. “Repeated personal observation convinced me that the advance along the Villa Verde Trail would prove to be costly and slow.”

From the Japanese perspective, according to the National World War II Museum, control of the islands was vital. “Loss of the Philippines would threaten Japan’s overseas access to foodstuffs and critical raw materials, especially oil, from the East Indies and Southeast Asia. For the Japanese, their ability to retain the Caraballo Mountains in northern Luzon was one key to retaining the Philippines.”

Led by Maj. Gen. William Hanson Gill, the U.S. Army’s 32nd Infantry Division, dubbed the “Red Arrow Division,” was assigned the grim task of routing out the enemy.

On Feb. 21, 1945, the slow slog began. For 119 days soldiers of the 32nd faced hellish conditions — constant skirmishes and hand-to-hand combat from an enemy eerily never more than a few feet way. Small unit fighting in caves and thick jungle were the norm, with the 32nd advancing only 35 yards a day at times.

While little publicized in the outside world, the Villa Verde produced a number of outstanding soldiers. The division earned an incredible 28 Silver Stars, 20 Distinguished Service Crosses and four Medals of Honor.

Arguably one of the most ironic was that awarded David M. Gonzales, since it involved undoing a near-fatal error on his own side.

Born to a Mexican-American family in Pacoima Park, California on June 9, 1923, David Maldonado Gonzales was working at a semi-skilled machine shop before enlisting in San Pedro on March 9, 1944. By the time he’d arrived on Luzon, he was a private first class in Company A, 127th Infantry

On April 25, Company A was pinned down in a slugfest for the First Salacsac Pass. The Army Air Forces, which by then had undisputed control of the air, tried to provide some support by skip bombing — pinpointing enemy caves and tunnels and using delayed-action fuzes to destroy their defenses. As Company A advanced apace, however, one of the 500-pound bombs fell short of its intended target and exploded on the company’s perimeter, burying five soldiers.

Immediately, Pfc. Gonzales grabbed an entrenching tool and crawled 15 yards up, unmindful of the intense sniper and machine gun fire over the open ground. There he found his company commander, Capt. Sheldon M. Dannelly, already there and trying to dig up his men — just before a burst of machine gun fire killed him.

Rushing up to take his place, Gonzales used his entrenching tool and his bare hands to find his entombed comrades, pulling one alive out of the sandy earth. Apparently judging that rescue while lying down too slow, he stood up to uncover a second soldier faster. He had just rescued his third man when he was mortally wounded by enemy fire. Later, after the Japanese had been driven back at last, the remaining two soldiers were located and dug out, still alive.

After over 100 days of fighting the 32nd Division achieved its objective, but at a high cost. It had suffered 825 men killed, 2,160 wounded and 6,000 troops evacuated from the front line due to disease, malnutrition and battle fatigue, while the Japanese withdrew after suffering 5,750 casualties. Gen. Gill was speaking for everyone involved by declaring that “the 32nd had gained too little for what it had lost.”

On Sept. 2, 1945, Gen. Yamashita personally surrendered to the 32nd Infantry Division, where, according to an official interrogation supervised by the Sixth Army Assistant Chief of Staff G-2, Yamashita noted that he considered the 32nd Infantry Division the best his troops encountered both on Leyte and Luzon.

The surrender, according to Gill, was “a glorious finish to this long bitter struggle.”

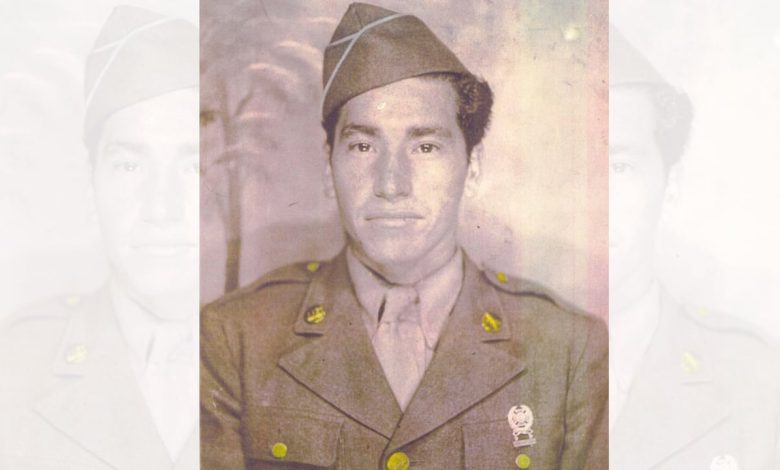

Capt. Dannelly, who had already received a Distinguished Service Cross, received a posthumous oak leaf cluster for his self-sacrifice on April 25, 1945. On Dec. 8, 1945, President Harry S. Truman awarded a posthumous Medal Honor to David Gonzales’ family… or so everyone thought. For over five decades Gonzales’ photograph was hung in the Pentagon’s Hall of Heroes, family and acquaintances, especially a witness Lt. William W. Kouts, one of the three men Gonzales is credited with saving, reported that it was the wrong man. The error was not corrected until 2002.

David Gonzales’ remains were transported home on a funeral train on Feb. 2, 1949, and re-interred at the New Calvary Catholic Cemetery in San Fernando, California. In addition to the Medal of Honor, Gonzales received the Bronze Star and Purple Heart. His name has since been commemorated on a local Army recruiting station, a Probation Department camp in Malibu, the David M. Gonzales/Pacoima Recreation Center and, as of November 2015, a junction of the 5 and 118 freeways, now the David M. Gonzales Memorial Interchange.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here