The Long And Short Of It

It’s hardly a secret that the revolver is making a bit of a comeback. After decades of scorn, the cool kids are shooting wheelguns again. As proof that I am a trendsetter with visionary powers, I have never stopped using revolvers.

As I age, some remnants of a misspent youth have emerged. An old back injury has made carrying a heavy handgun on my belt for extended time periods uncomfortable. For the past several years my primary, all day, all the time, if-I-have-pants-on-it’s-with-me carry gun is a J-frame Smith & Wesson Model 340. This Scandium-frame revolver is chambered in potent .357 Mag. It has a 1.88-inch barrel and weighs only 14 ounces. My gun has been tweaked a bit by the folks at Mag-Na-Port and, of course, the stubby barrel is ported. I may still strap on a full-size wheelgun, M1911 or polymer wonder-gun when I have places to go, but this handgun is like a loyal dog and is always with me, almost regardless of the weather or sartorial demands.

Conventional wisdom holds it to be true that barrel length matters a great deal. To hear some experts tell it, long barrels provide the fastest velocities, while short barrels can barely spit the bullet out the muzzle. I even had one guy at the range jokingly tell me, “If the little barrel is ported, the bullet may go backward and blow your gun up.” So, is it a ballistic mistake to carry that little J-frame? Will it get me killed on the streets? A lot of internet experts seem to think it will.

I always want proof, so I set out to find the answers myself. I decided to gather up all the .38 Spl. +P and .357 Mag. ammo I could and test the velocities from multiple revolvers of varying barrel lengths.

An extended range session chronographing ammo through short-barreled, centerfire wheelguns is sure to yield both plentiful data and sore hands • Mag-Na-Porting a barrel reduces both felt recoil and muzzle rise • A compact wheelgun serves well as a constant companion as it is small, light and reliable, with a simple manual-of-arms.

I didn’t want this to turn into a multi-year project, so I stuck with the bigger names in ammo making and didn’t include any boutique loaders; sorry, guys. In this time of ammo shortages, I expected that most companies would only have an SKU or two in stock. I asked them to send any ammo they had available for those two cartridges, figuring I would wind up with a dozen or so ammo products to test. All but one major ammunition manufacturer provided ammunition for this review. Much more than I expected, even: The result was 91 individual files of velocity info with nine different guns. I used 89 of them for the following results. I had two files with the ninth gun that I culled after I took that gun out of rotation early in the test.

For the .38 Spl. +P, I used a Ruger LCR equipped with a 1.87-inch barrel and weighing 13.5 ounces. I wanted to keep the snub-nose gun, which is the primary reason for this project. It is chambered in .38 Spl. because I wasn’t sure if the longer cylinder in the .357 Mag. would be a factor when shooting .38 Spl. ammo.

I checked the crossover where I tested the same ammo in the LCR and the Smith & Wesson, non-ported, .357 Mag. J-frame. The barrel lengths are identical, and there is only a slight loss in velocity. The more capacious magnum-chambered gun is a paltry 46.81 fps slower on average, due to the reduced pressure.

Why +P ammo? Because standard .38 Spl. ammo is not much of a thing anymore. Try to buy some with a bullet made for defense and you will see. Like Bigfoot, it may exist, but it’s hard to find in the wild. Besides, most people with .38 Spl. carry guns load them with +P ammo. I did want to include wadcutter ammo as some folks I know are carrying that for defense these days, but none was available from any of the participating ammo makers.

The middle gun for both cartridges was the sturdy Ruger GP100, 7-shot, .357 Mag. with a 4.2-inch barrel. The GP100 is a bigger handgun, weighing 40 ounces. I didn’t find recoil from any of the ammo products objectional. One note is that the 4.2-inch barrel seems to be optimal for most defensive ammo. Some of the ammo didn’t show a very big gain in velocity when moving up to the 5.5-inch tube. Three loads were actually slower with the longer barrel.

Finally, I dug around the gun vault to find a 6-inch-barreled handgun, and wound up with one of my old Ruger Blackhawk revolvers with a 5.5-inch barrel. It’s chambered for .357 Mag., weighs 3 pounds and is built like an anvil. I used this gun in competition for many years and shot thousands of low-power .38 Spls. loaded with Trail Boss. Obviously, it handles full-power .357 Mag. ammo with ease. I believe that a single-action design is best to use with powerfully recoiling chamberings and that .357 Mag. Blackhawk behaved sweetly at the range, rocking back and up in my palm.

Most small-wheelgun aficionados accept the slightly diminished velocity and muzzle energy as a fair trade for enhanced concealability • An EDC gun may have to be adaptable to different modes of carry, such as an ankle holster • The small revolver’s biggest drawbacks compared to semi-automatics are its low firepower and slow reloading speed.

The only change for the .357 Mag. ammo was replacing the LCR .38 Spl. with an SP101 in .357 Mag. That gun has a 2.25-inch barrel and weighs 26 ounces. I also used my ported Smith & Wesson Model 340 and a nearly identical non-ported Model 360, both with 1.88-inch barrels. These were for a side test where I wanted to see the effect of porting. I tested five different ammo products in those guns to see if the porting made any difference. The three .38 Spl. +P ammo products tested showed that the ported gun was 3 fps faster on average than the non-ported gun. This was skewed a bit by the Federal 120-grain Punch ammo, which was 35 fps faster in the ported gun.

I also tested two .357 Mag. loads, and the difference on average was that the ported gun was 88 fps slower, retaining 97.6 percent of the velocity of the non-ported handgun. The bottom line is, statistically speaking, the recoil-reducing ports have no significant effect on muzzle velocity. For the record, I failed to have even a single, solitary bullet go backward.

Each load was tested with a minimum of five shots. I did all the firing indoors in a climate-controlled shooting range. Velocities were measured by Doppler radar. (See the accompanying sidebar below.)

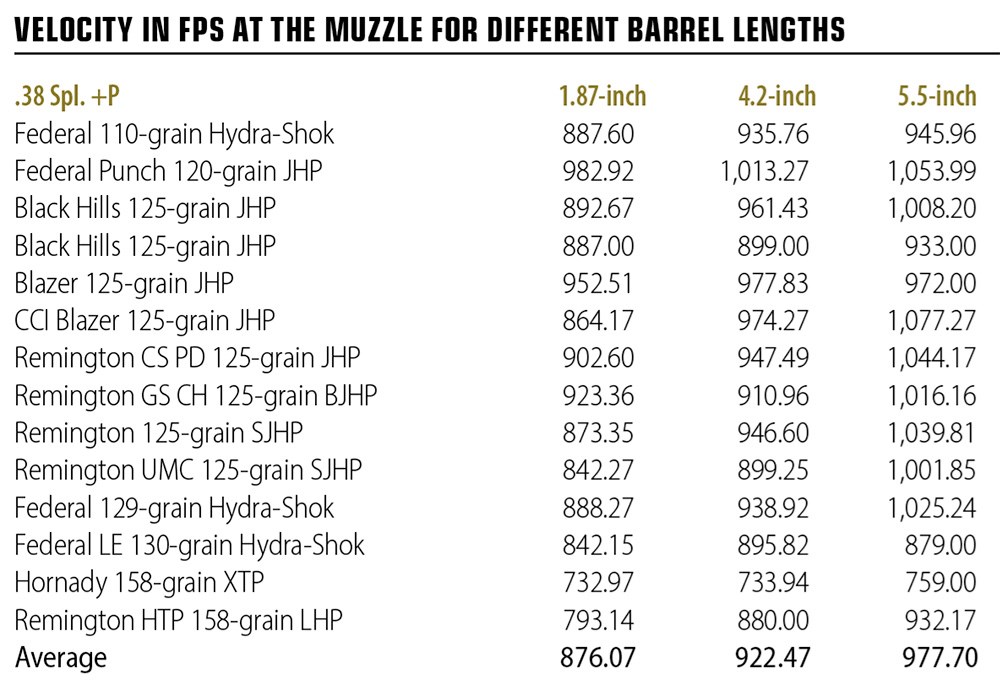

Using the .38 Spl. +P ammo and testing 14 different ammo products, the difference between the 4.2-inch and 1.87-inch barrels averaged 61.8 fps. That is 94.63 percent of velocity retained. The Remington Golden Saber Compact Handgun BJHP 125-grain ammo was actually 12.5 fps faster in the LCR, showing that ammo designed for short barrels works well in short barrels.

Using the .38 Spl. +P ammo and testing 14 different ammo products, the difference between the 4.2-inch and 1.87-inch barrels averaged 61.8 fps. That is 94.63 percent of velocity retained. The Remington Golden Saber Compact Handgun BJHP 125-grain ammo was actually 12.5 fps faster in the LCR, showing that ammo designed for short barrels works well in short barrels.

The average difference between the 5.5-inch barrel and the 1.87-inch tube was 86.63 fps. The short barrel retained 89.6 percent of the velocity. In .38 Spl. +P, the highest velocity in a 1.87-inch barrel was the Federal 120-grain Punch at 983 fps. Blazer 125-grain was close on its heels at 952.51 fps.

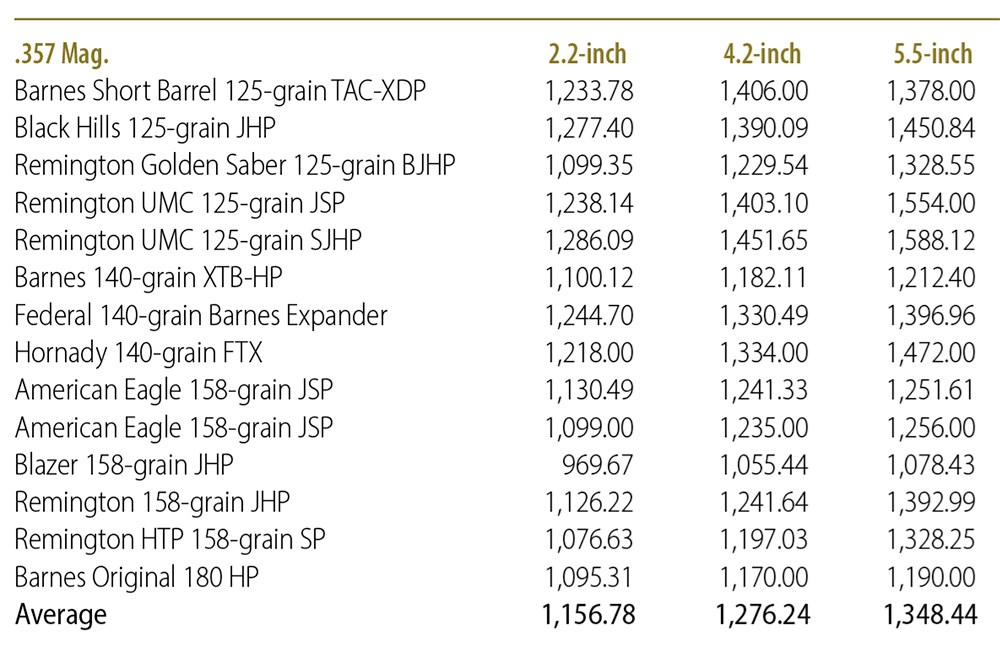

When I compared the total average velocity for the .38 Spl. +P in the 1.87-inch barrel with the .357 Mag. ammo average in the 2.2-inch barrel, the difference was 280.68 fps faster for the magnum. That’s about a 32 percent increase in velocity. Energy is exponential to velocity, so the gain is even higher. Using the average velocity figures with the short barrels and a 125-grain bullet, the .357 Mag. shows an increase of 70 percent in energy more than the .38 Spl. It’s clear that, ballistically, the .357 Mag. is a better choice.

This test is about exterior ballistics; the muzzle velocity. It’s also important to choose a bullet that will expand and penetrate if you are going to use it to protect your life. I lean to the premium bullets that are loaded in the ammo designed and marketed for defensive use.

I reached a few conclusions after several range sessions with these handguns. The reason for all this was to determine if a short-barrel handgun is giving up too much ballistic performance for the sake of easier carry. The answer is unequivocally no. A 2-inch barrel retains, on average, 94 percent of the velocity of a 4-inch gun. If you select ammo designed for a short barrel, you give up even less. The results should assuage concerns about opting for a shorter barrel.

The second conclusion was hard to ignore: Snubnose .357 Mag. revolvers kick. Recoil can reach 20 ft.-lbs. in the lighter revolvers. That’s the same as a .44 Mag. in a large revolver, only with a smaller grip and sharper impulse. The .38 Spl. +P ammo in sub-16-ounce guns is no slouch either, with as much as 12 ft.-lbs. of recoil. In comparison, the full-size Glock G17 in 9 mm generates only about 6.5 ft.-lbs. of recoil.

That is a lot of recoil in a defensive handgun. These little guns may be easy to carry, but they are brutal to shoot. Powerful ammo in ultra-light handguns generates recoil. There is simply no way you can reduce the felt recoil without reducing the effectiveness on target.

Usually, we are only shooting the high-test ammo in small amounts. I end each practice session with one cylinder full of carry ammo—five shots—every now and then. Shooting 50 or 60 rounds of high-horsepower .357 Mag. ammo from snub-nose revolvers in one session, as I did multiple times for this test, is too much. I have one file from a Scandium J-frame .357 Mag. that is only four rounds as I just could not make myself shoot the last round of the day.

The author also tested ported barrels to see if they suffered a substantive loss of velocity and muzzle energy • A shooting glove is a necessity when firing anything more than a few cylinders through small, centerfire revolvers.

I have provided a lot of information here on the exterior ballistic performance of both .38 Spl. +P and full-power .357 Mag. ammo. You need to make a choice that works for you. I can handle the recoil for five or fewer shots pretty well (because I practice) and if I have to shoot in defense of my life, I suspect the adrenaline rush will help mitigate the effects of recoil. Still, I’ll concede that low-recoil ammo may be better for some people. If you simply can’t hit the target, there is little point in using the more powerful ammo. This is a recoil level that might be difficult to train with if you are not a hardcore, experienced shooter.

Make no mistake, anytime you choose a snubnose revolver for a carry gun there are compromises. Every chambering has a sweet spot in terms of ideal barrel length—and it’s typically longer than 2 inches. Slightly straying from that ideal for the sake of concealability, though, is practical. No matter which ammo you use, your split times between shots are going to be higher than, say, a bigger gun with lower-recoil 9 mm ammo. If you use full-house .357 Mag. ammo rather than .38 Spl., split times will be even longer. I try not to plan my defensive strategy on how much I will miss. So, the first shot is the most important and I want all the whack I can put into it.

No matter what you read on the internet, there is a difference in handgun cartridges. Physics dictates that there must be, but they are all underpowered compared to most rifles. If my second shot is .25 seconds slower with a .357 Mag. versus a .38 Spl. I still feel I made the right choice with the more powerful ammo. You may not agree.

If you carry a snubby, it’s important that you practice a lot. These are difficult guns to master. As for carry ammo, look at the numbers and pick what you think will deliver the ballistics you want. Then burn up a box or two of the carry ammo in your gun to see how well you can manage.

Just don’t expect to do it all in one range session.

Garmin Xero C1 Pro Chronograph

Garmin Xero C1 Pro Chronograph

I had been using a Doppler radar chronograph since it took the market by storm a few years ago. While it has been aggravatingly troublesome at times, the easy set up made it worth using. Still, in that time I all but went broke feeding the swear jar.

Halfway through this project I got my hands on a Garmin Xero C1 Pro Chronograph. It’s a tiny package, but looks can be deceiving, and the company found a way to pack a lot of features into a small unit.

The Garmin Xero C1 Pro Chronograph uses Doppler radar to measure bullet speed. It pairs through Bluetooth to a phone or other device to transmit and store the data. There, it displays pretty much everything you need to know and even a bit more. This Garmin works so well that I took money out of the swear jar.

I used the Garmin indoors with handguns as well as at an outdoor range with several handguns and rifles in multiple chamberings. That included using it when others shooters were on the range and in a wide range of temperatures. The rechargeable battery didn’t even break a sweat on the coldest of days.

My only issue is transferring the data from my phone to my computer. I have to e-mail each file. I would love a removable card that can move it all in one batch.

So far, it’s the easiest to use and most trouble-free chronograph I have owned. I think this one will lead the pack for a long time.–BT

MSRP: $599.99; garmin.com

Read the full article here