This American soldier saved Charlemagne’s cathedral in World War II

As the city of Aachen, once the seat of power of the emperor Charlemagne, lay in ruins in World War II’s bitterest winter, an American soldier worked feverishly alongside German civilians to make sure its ancient cathedral remained standing. Capt. Walter Johan Huchthausen of Perry, Oklahoma, strove tirelessly to stop the building from collapsing and ensured it would be preserved as it is today.

The son of a German immigrant father, Huchthausen was a rising star in the field of architecture. His strong grasp of design principles and enthusiasm for history brought him accolades for his work and professional success. After receiving a Master’s degree from Harvard, he worked in New York and Boston and eventually became an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Minnesota.

Becoming a Monuments Man

Huchthausen’s German heritage was important to him. He studied abroad in Germany on a fellowship for Harvard prior to the war and mastered the language with native proficiency as he worked alongside German museum professionals. His connection with the German language and culture would later become vital to his success as a U.S. Army Monuments Man tasked with preserving valuable historical artifacts.

After World War II broke out, Huchthausen, then age 38, volunteered for military service in 1942, joining the U.S. Army Air Forces. His service in the USAAF would be short-lived, however. Wounded badly by a V-1 “flying bomb” in London in June 1944, he joined the U.S. Army’s European Civil Affairs Division and was selected as a talented candidate for the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives program, whose officers were popularly known as “the Monuments Men.” As the Battle of the Bulge raged in December 1944, Huchthausen joined the Ninth Army as its Monuments officer.

Attaining the rank of captain, he was nicknamed “Hutch” by his comrades, who likely struggled to pronounce his German last name.

Huchthausen communicated well with German POWs and local civilians and thus, within a relatively short timeframe, he was able to locate 30 hidden caches of art stashed away by Nazi officials — salvaging both historical German artifacts and looted objects from occupied countries. He was known for being especially hardworking and was admired by his colleagues for his organizational talents and attention to detail.

In the ruins of a royal city

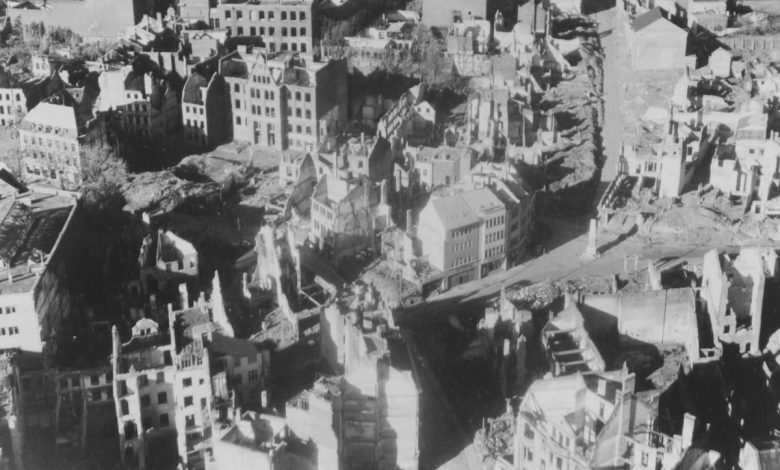

After working briefly in France, he distinguished himself after arriving in the shattered ruins of Aachen, a city ripped apart both by external and internal strife. Its history as the citadel of Emperor Charlemagne, the first ruler of what would become the Holy Roman Empire, gave it special status — not only to locals but to Adolf Hitler, who saw it as a propaganda symbol.

As the U.S. Army approached, Hitler ordered the city to be defended to the last man and destroyed totally rather than surrendered. Local civilians were at first prevented from evacuating by the Schutzstaffel, better known as the SS, and subsequently forced from their homes as Nazi officials prepared for a deadly siege that began in early September and became one of the war’s bloodiest urban battles.

Treated brutally by the SS, many civilians hid in various locations inside the city and tried to break out to safety later. Photos taken by the U.S. Army during the battle of Aachen note that elderly German residents were fired upon by Nazis with automatic weapons as they tried to flee. American soldiers later rescued several infirm elderly women who were nearly gunned down while trying to escape through the ruins.

Once a magnificent structure with its own treasure chamber, Aachen’s cathedral had already suffered bombing damage throughout the war. In the early war years it had been protected by local German youths who formed a volunteer fire brigade to preserve the church.

However, the cathedral was on its last legs. The ferocious battle that ended on Oct. 21 had seen tanks tear through the city and buildings ripped apart by shellfire. The cathedral was in danger of collapse.

Saving the cathedral

Arriving in January 1945, Huchthausen came to the rescue. Creating his own headquarters in the city’s Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, he set about identifying and collecting the cathedral’s numerous altarpieces and artifacts to preserve them. Huchthausen successfully organized and led local German civilians to locate missing objects and start repairing the site.

He used his architectural expertise to rescue what he could. Under his leadership, civilians repaired the roof, preserved paintings and covered bomb-damaged windows. He successfully reinforced the cathedral’s buttresses to stop them from caving in and strengthened the interior structure — saving it from collapse.

Challenged by a reporter about why he cared about preserving a site in the Third Reich, Huchthausen replied that its history was world heritage. “Aachen Cathedral belongs to the world and if we can prevent it from falling in ruins…we are doing a service to the world,” he said.

Killed in action

Tragically, that statement defining his approach to his work was published two days after Huchthausen was killed in action on April 2, 1945. Working closely behind the Ninth Army’s frontlines, Huchthausen and his assistant Lt. Sheldon Keck, formerly a conservator of the Brooklyn Museum of Art, were driving in search of a stolen artifact when they came under fire from a machine gun. Huchthausen was killed instantly, falling on top of his comrade as the vehicle overturned. Keck survived.

Fellow Monuments Man Maj. Walker Hancock wrote a touching tribute to Huchthausen after his death. “The buildings that Hutch hoped, as a young architect, to build will never exist,” he wrote, “but the few people who saw him at his job — friend and enemy — must think more of the human race because of him.”

Huchthausen is buried in the Netherlands American Cemetery in Holland, and was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart with oak leaf cluster.

Zita Ballinger Fletcher previously served as editor of Military History Quarterly and Vietnam magazines and as the historian of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. She holds an M.A. with distinction in military history.

Read the full article here