When U.S. Marines Fought in China: The Boxer Rebellion

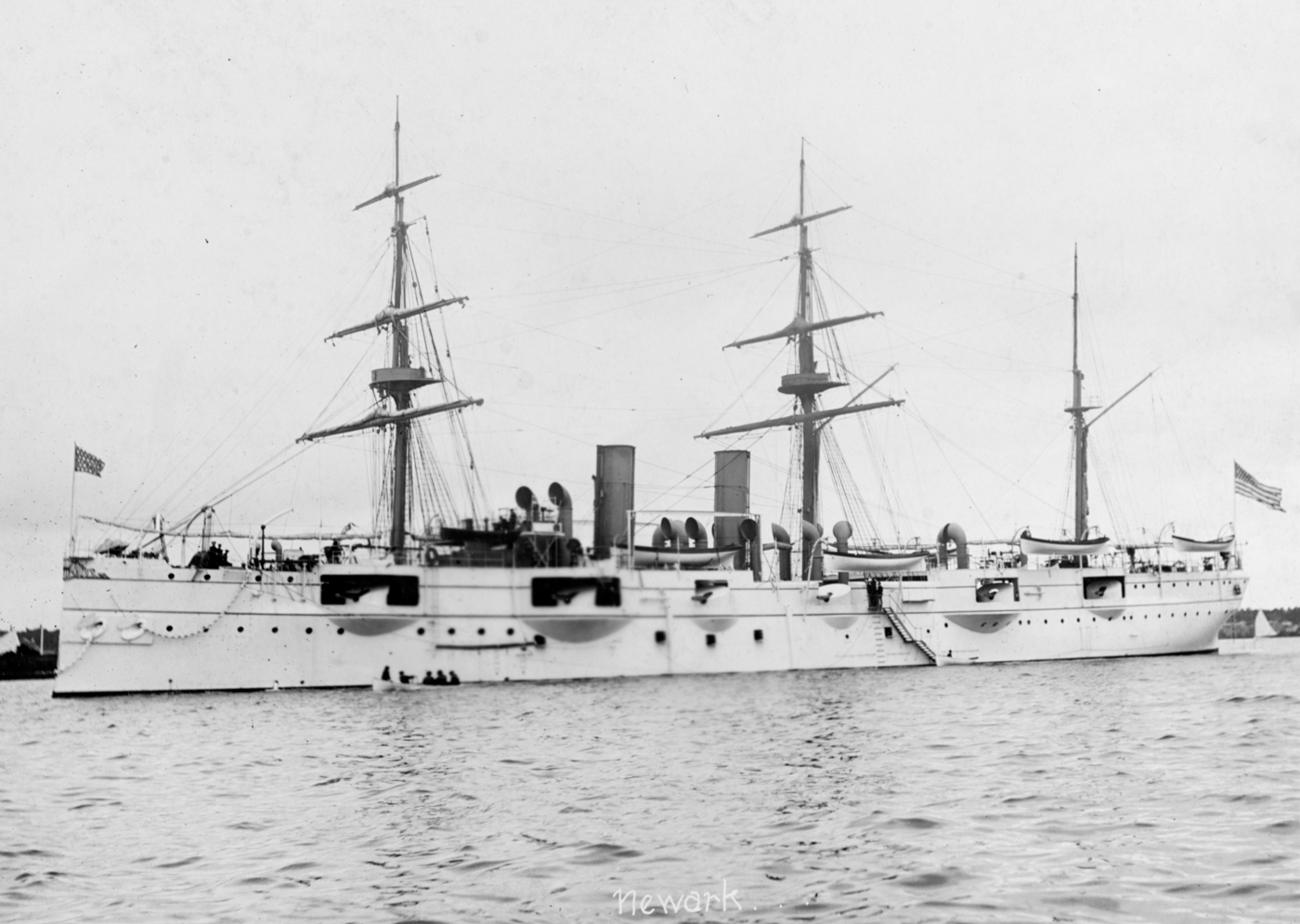

The turn of the 20th century was a turbulent time in China. As usual in those days of western expansion, the U.S. military was right in the middle of it. Act One was a little known, very bloody uprising called the Boxer Rebellion. Roots of that uprising run deep and complex but it’s fairly easy to imagine something that might have happened at the start of it all in May 1900 aboard the battleship USS Oregon (BB-3) or cruiser USS Newark (C-1), two American warships moored at Taku some 115 miles from the Chinese capital at Peking (now called Beijing).

Private Dan Daly of the Marine Detachment is seated somewhere on the fantail cleaning his Springfield Model 1892 Krag–Jørgensen rifle when a corporal arrives with orders. “Get them rifles assembled and make up a marching pack.” The corporal waves a hand at the shoreline. “We’re going ashore to mix it up with them Boxers.”

“Is it just us, Corporal?” Pvt. Daly was a little leery of an assignment to take on bloodthirsty Chinese rebels they’d been hearing about with just some 50 men from the two Marine detachments aboard Oregon and Newark.

“Relax, Private Daly.” The corporal swept an arm over the other allied ships in the harbor. “We’re headed for Peking with Royal Marines and there’ll be some Japanese Marines and a passel of troops from Germany, Italy and Austria. You got nothing to worry about.”

Private Dan Daly and a bunch of other Americans had a lot to worry about heading for a bloody clash with the Boxers that would develop into an infamous 55-day siege of the Legation Quarter at Peking, but they didn’t know that at the time.

The biggest mystery to most allied forces heading for Peking was their enemy. Who were these guys? And Why were they called Boxers? Answers were provided by their skipper, Captain John T. Myers, known as “Handsome Jack,” for his good looks and luxurious mustache.

Boxer Rebellion

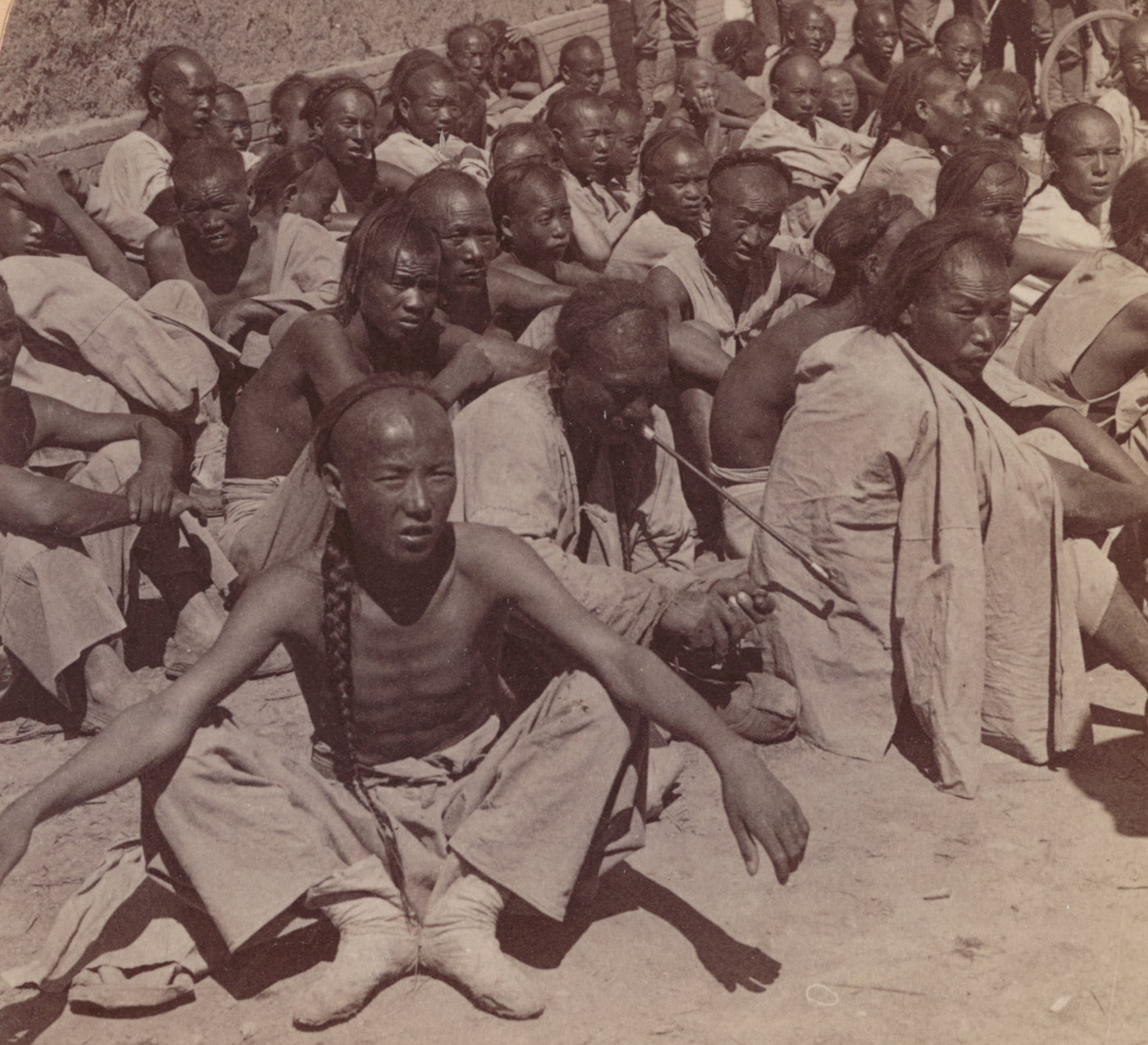

The so-called Boxers were a growing group of ultra-nationalist rural Chinese from northern reaches of the country who organized as “The Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists.” They practiced mysterious forms of close combat and arcane martial arts. Hence, the nickname.

Most of them were devout Buddhists and they thought Christian missionaries in China were trying to import a foreign religion. After some successes attacking remote Christian missions, the Boxers expanded their objections to foreigners of any sort, especially western European businesses they felt were exploiting resources without much reciprocal gain for the Chinese. Things got hot in a hurry as growing groups of Boxers, picking up converts along the way, headed for Peking in a bid to drive all foreigners out of China.

This situation presented a problem for Dowager Empress Cixi (SEE-She) who had originally turned a blind eye to the Boxer attacks against Christian missionaries, Chinese Christians, and other Westerners. It seemed to her like a local turmoil in distant rural areas and not much of a threat to legitimate foreign trade. And the Empress was bound by the Treaty of Tientsin signed in 1860 following a Chinese civil war, which gave Westerners permission to do business in her country. By 1900, American businessmen — bankers, manufacturers and energy companies like Texaco and Standard Oil — were flocking to China in order to sell goods to the country with the largest population in the world.

But the Boxers were getting stronger and edging closer to the Imperial City every day. That put Cixi in a tight spot. If she openly opposed them, the Boxer mobs might turn on her government and she’d be facing a second civil war. As a compromise, the Empress officially dropped her opposition to the Boxers. At the same time, she ordered all foreign businessmen to shut down any operations in the countryside and move to Peking. It didn’t sit well with big business reps and diplomats who promptly wired their home governments for support.

With throngs of Boxers on the move, they wanted troops to enforce treaty agreements and protect their interests — plus a large segment of Chinese Christians were now now jam-packed into the crowded Legation Quarter of Peking. Most of the nations doing business in China felt obligated to comply, but in 1900 there were no foreign military forces of any nation based in China. First aid would have to come from forces aboard ships in Chinese ports or offshore.

Send in the Marines

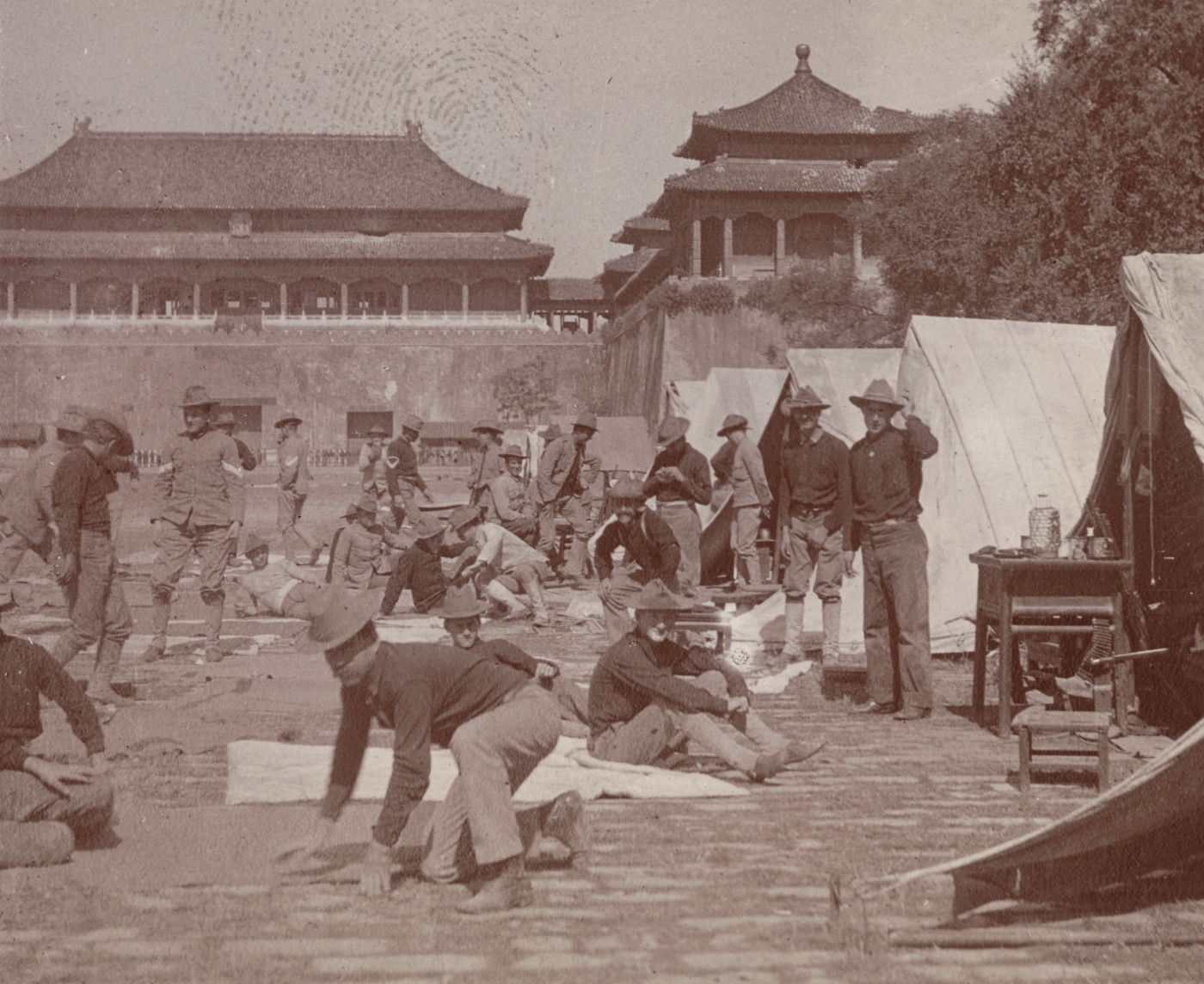

The foreign military force including Myers and his Marines arrived at Peking in June and immediately set up camps in the Legation Quarter. It was a struggle trying to coordinate security measures since few of the Marines or naval infantry had an ability to speak any kind of foreign language.

It was a classic “Tower of Babel” inside the legation walls, with diplomats and businessmen from America, the UK, Russia, Japan, France, Germany and Italy all demanding services and priorities. It was clear to Captain Myers as senior U.S. Marine that more troops would be needed if the Boxers — now a considerably sizable force — laid siege to the Legation Quarter.

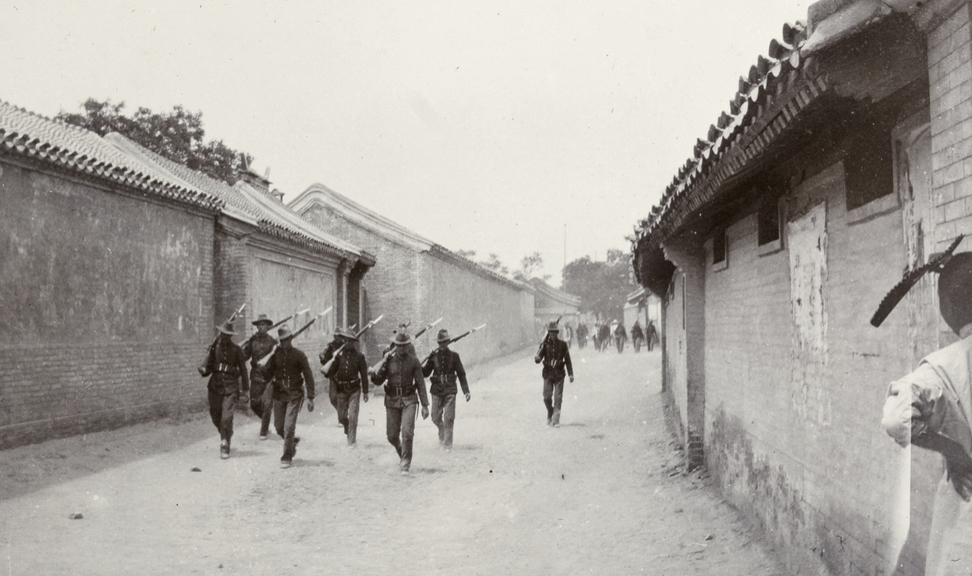

He fired off messages asking for reinforcements which he understood would likely take more than a month to arrive at Peking. While there were rabble-rousing Boxers all over the Imperial City, they had busied themselves mostly with attacking Chinese Christians or foreigners caught outside the legation walls. The American Marines and their international counterparts mostly patrolled within the Legation Quarter, keeping peace and planning actions if the Boxers made a concerted effort to storm the walls.

Meanwhile, 115 miles away at Taku where various nations were attempting to muster a large force in response to pleas for reinforcements at Peking, Boxers killed a German diplomat. That tripped a violent trigger. U.S. and European naval forces seized the Chinese forts at Taku and began landing troops without asking permission from Peking. The Chinese government promptly severed diplomatic relations with all Western powers. And in a towering snit, the Empress ordered her Chinese Army forces to side with the Boxers and expel all foreigners by force.

What followed was a combined Chinese Army and Boxer full-scale assault on the Legation Quarter with small arms, automatic weapons, and artillery. It was the beginning of what was to become known around the world as the infamous 55-day Siege of the International Legations or Siege of Peking.

Manning the Walls

While they waited for the international elements mustering at the Taku Forts to ride to the rescue, the forces at Peking’s Legation Quarter were already in a fairly stiff fight. The weakest point in Legation Quarter defenses was the southern portion of the surrounding bulwarks known as the Tartar Wall. Naturally, that’s where Capt. Myers planted his Marines. It was a tough proposition with some loyal Chinese guards on the right and a unit of German naval infantry on the left. Myers had to rely on hand signals and pantomime to communicate with his flanks.

The Marines at the Tartar Wall were not well set up for defensive combat. The basic shoulder weapon was a bolt-action Springfield Model 1892 rifle (Krag–Jørgensen) chambered for the US .30-40 Krag cartridge. Officers and NCOs carried Colt M1900 semi-auto pistols firing a .38 ACP round. The lone machinegun available was a Colt Browning Potato Digger – the Model 1895 — which was notorious for dangerous over-heating and required a tripod. The weapon could not be fired from a prone position due to the constant downward swing of its loading lever, which earned it the nickname “potato digger.”

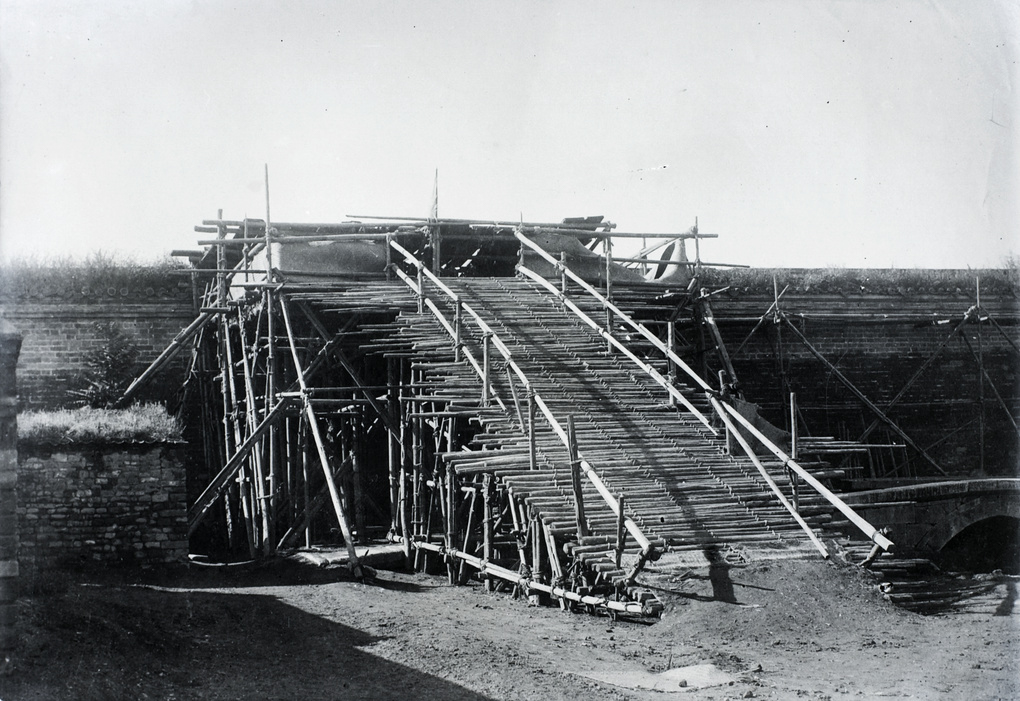

Despite the lack of firepower, the Marines had the advantage of the high ground during the initial battles at the legation walls. Assaulting Chinese built siege towers and other elevated structures in attempts to get over the walls or put riflemen into position for plunging fire.

The key was to reach 45 feet, at which height, the Chinese could leap from the towers and assault down into the quarter grounds. Defenders fought hard to keep Chinese sappers from reaching that goal. At several times during the fighting, Chinese towers were only a few feet away from walls and snipers were deadly threats. The first four Marines killed in fighting at the Tartar Wall all fell to Chinese sharpshooters firing from adjacent siege towers.

The defenders at the legation walls were facing a mix of regular and irregular forces including Buddhist Boxers, Muslim Boxers and units of the Peking Field Army, regulars with tactical discipline and light artillery. When the siege towers and structures failed to breech defenses, the assaulters tried burning buildings around the legation walls. They also dug some elaborate tunnels in efforts to gain access. Defenders countered it all which led to all-out ground assaults on the Legation Quarter though a number of gates.

On the Offensive

From mid-June through early July, the Chinese pressed their attacks relentlessly. Marines were exposed to enemy fire night and day. Particularly dangerous were efforts to reach firing positions along the Tartar Wall. They had to run up a ramp which was totally exposed to incoming fire. Things got desperate for the defenders on the night of 30 June when Chinese fire drove American and German defenders off the wall entirely. It was push and shove, fire and fall back for days as Chinese assault forces steadily encroached and built taller siege towers. By early July it was obvious to all that the defenders could not hold much longer. If help didn’t arrive in a hurry, the Legation Quarter would fall.

In typical Marine fashion, Capt. Myers assembled a mixed force of American Marines, British Royal Marines and some Russian Naval Infantry to go on the offensive. On 3 July, Capt. Myers led a platoon-size night counterattack against Chinese barricades and achieved complete surprise.

Allied forces killed a sizeable number of Chinese and drove the rest of them away from the barricades. With only two Marines killed in the action and a painful wound for Capt. Myers, the Chinese got shy again and the Legation was no longer in immediate danger of being overrun. But the heat was still on at the Legation Quarter as Chinese forces continued to attack with artillery and automatic weapons.

The clock was ticking loudly for everyone inside the Legation Quarter.

Seymour Expedition to the Rescue?

The situation was not much better among the Eight-Nation Alliance, the international forces ordered to relieve defenders at Peking. Part of the larger China Relief Expedition, an international force including more U.S. Marines plus British troops and contingents of German, Russian, French, Japanese, Italians and Austrians had boarded trains at Taku headed for Tientsin where they planned to continue by rail for Peking.

Organized as the Seymour Expedition and named for British Vice Admiral Edward Seymour, Commander of the Royal Navy’s China Station, the troops were stopped cold by Boxers at Tientsin. Under intense pressure, with casualties mounting, the Seymour expedition had to dig in and defend at a series of fortress structures. At this point, the intended Peking rescuers needed rescue.

More Marines landed from American warships at Taku under Major Littleton W. T. Waller and headed for Tientsin to link-up with the besieged Seymour force. With only 130 men ashore, the Marines promptly got involved in a melee with Boxers, lost a dozen men killed, and had to retreat. Waller requested immediate reinforcements to handle what was rapidly becoming a bloodbath at Tientsin as well as Peking.

Everyone involved in the Boxer Rebellion from Taku to Tientsin to Peking needed rescue. At Peking, defenders were starving, subsisting mostly on horsemeat. The Seymour Expedition was pinned down at Tientsin and Waller’s Marine relief force was stuck just south of that city and under intense pressure from Boxers. At that point, the U.S. Army was called in to square away the mess and pull everyone’s irons out of a very hot fire.

Turning the Tide

Mounting a massive landing and counterattack from his headquarters in the Philippines, American General Arthur MacArthur, Jr. (father of another General MacArthur who gained fame in WWII and Korea), sent two battalions of his 9th U.S. Infantry plus a battery of artillery to China. They came ashore with orders to relieve the forces at Tientsin and then head for Peking to rescue the legation defenders.

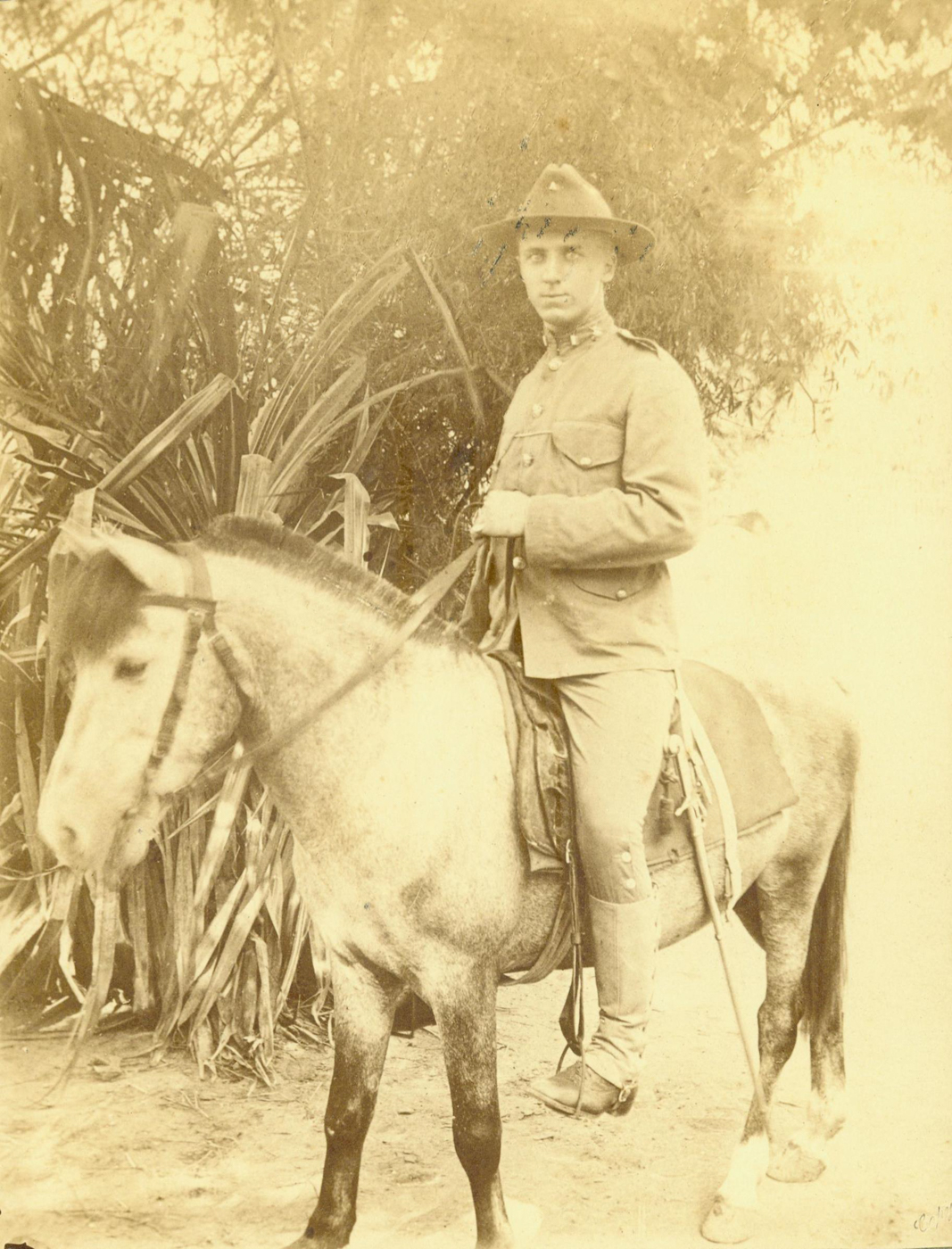

The soldiers attacked and seized Tientsin in mid-July while yet more troops from the U.S. Army’s 14th Infantry Regiment plus a reinforcing contingent of Marines landed to back MacArthur’s play in China. That Marine element included an 18-year-old First Lieutenant named Smedley Butler who won a brevet promotion for battlefield valor during fighting with the Boxers.

With Tientsin relieved by the 9th Infantry, a resupply route from Taku Ports was opened and secured. The American command now cobbled itself together and set out for Peking. On the march in July 1900 was a force of 20,000 men including 2,500 Americans, most of them soldiers with only a relatively few Marines.

It was a brutal summer in China and heat began to cause casualties on the march. It was especially hard on the Marines who were unprepared for a long, blistering hot slog having spent much of their deployed time aboard Navy ships. At one point, a third of the Marines on the march fell out as heat-casualties. It was not the Marine Corps’ most sterling performance and the Marine contingent contributed little to the fight when the relief expedition battled Boxers along the route to Peking.

The international force entered Peking on 15 August with two basic missions: Fend off the Boxers surrounding the Legation Quarter and rescue trapped diplomats. Each country’s contingent had their own ideas about how that should be accomplished. Effective unity of command and control was lost almost immediately. Some contingents mounted assaults on the legation gates. The U.S. Army took the simplest route and simply scaled the walls under covering fire from soldiers on the ground. During these uncoordinated efforts, the Chinese mounted a desperate last-gasp offensive.

It was during that raging fight, that Private Dan Daly started his climb from obscurity to Marine Corps legend. Manning a particularly hard-pressed position along the Tartar Wall, Daly mounted a solo defense that resulted in 200 dead Boxers. All of them fell to Daly’s accurate and sustained rifle fire. The action would result in the first of two Medals of Honor awarded during Daly’s Marine Corps career.

Under pressure from the international forces at Peking, the Boxers abandoned the city. Many of them were captured and summarily executed. The Dowager Empress and titular head of the Chinese government fled and went into self-imposed exile for a year. The Boxer Rebellion was basically over at that point.

Conclusion

China eventually signed a Boxer Protocol, allowing all of the nations represented in the relief expedition to permanently station troops in the country. The U.S. Marine Corps took advantage of that and based the 4th Marine Regiment in China where they remained as “China Marines” until 1941.

Under the new treaty, China was forced to pay reparations for losses and costs created by the Boxer Rebellion. They couldn’t afford it and when the returned Empress failed at attempts to strike bargains with Western businesses, the Chinese government fell.

Twelve years later the ancient Chinese Empire collapsed and the nation became a republic under Sun Yat Sen. That lasted until 1927 when civil war erupted pitting nationalist forces against rural communists under Mao Tse Tung. Sensing chaos in China in 1937, the Japanese invaded and began a second Sino-Japanese War. Japanese imperialism and conquest started there. World War II soon followed.

In 1900, no one could have imagined that those wild-eyed radicals from The Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists would have such a profound effect on world affairs.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here