Why Justice Jackson is a fish out of water on the Supreme Court

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

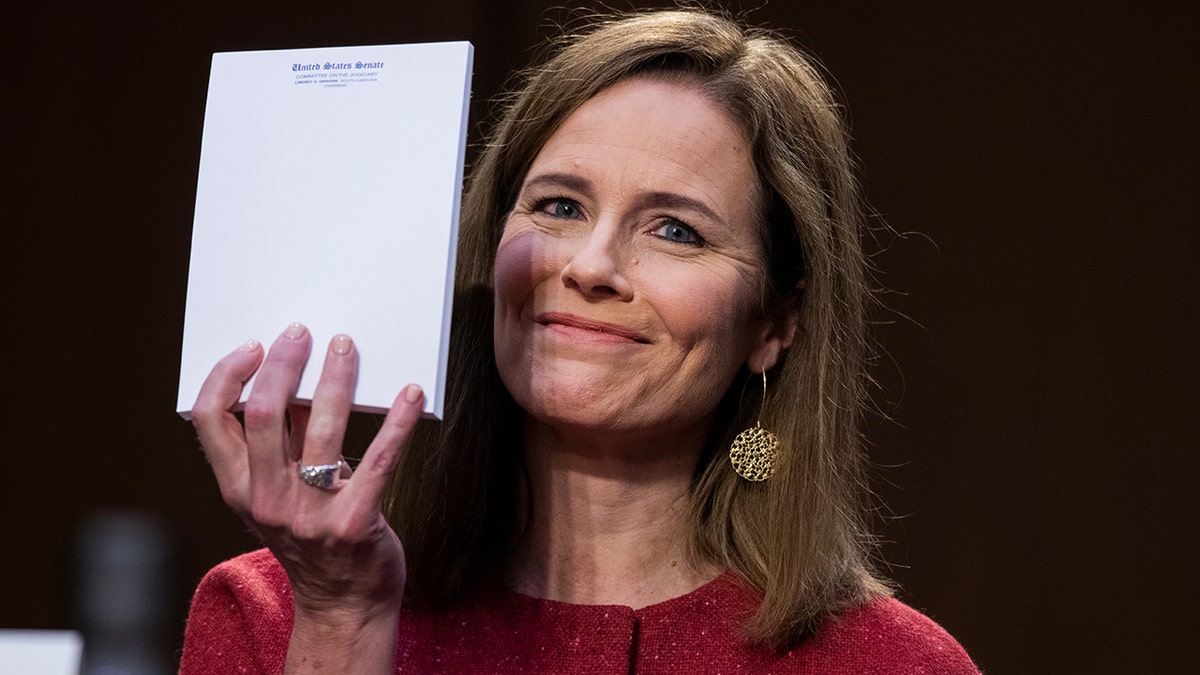

Much has been written in recent days about the war of words between Supreme Court justices Amy Coney Barrett and Ketanji Brown-Jackson in the opinions handed down in Trump v. Casa, Inc., the case involving an injunction issued in a case challenging birthright citizenship.

But as I pointed out in a Post on X Friday morning, Barrett’s decision was written on behalf of herself and the five other justices in the majority. The fact that Barrett was assigned this opinion by the chief judge (the chief judge decides who writes the opinion when he votes with the majority) is a signal that the other five justices turned her loose on Jackson. Such an unsparing smackdown of the most junior justice with a vastly different view of the judicial function would have been received much differently had it come from one of the other five justices in the conservative wing of the Court.

BARRETT EVISCERATES JACKSON, SOTOMAYOR TAKES ON A ‘COMPLICIT’ COURT IN CONTENTIOUS FINAL OPINIONS

But coming from another female justice, one with only two more terms on the Court than Jackson, it was the least harsh way to deliver the rebuke that the majority opinion represented. But the language was anything but gentle, and the point was anything but subtle.

If Jackson seems out of her element, there’s a reason. There have been many career paths followed by justices who have been appointed to the Supreme Court. But it is quite uncommon for someone to be appointed to the Supreme Court without meaningful experience at the level of an appellate court, as is the case with Jackson.

Justice Elena Kagan charted a very different course to the Supreme Court, largely through academia. However, before joining the court she did serve in various DOJ positions in the Clinton administration, and as the solicitor general of the United States under President Obama. The solicitor general argues cases on behalf of the United States before the Supreme Court. Kagan also wrote extensively on legal issues during the nine years she served as both a professor and dean at Harvard Law School.

Another outlier was Justice Lewis Powell, who joined the Court in 1972 directly out of a large law firm where he had practiced corporate law for 35 years, never having been a judge in any court at any level.

Jackson did not join the Court with no experience as a judge as was the case with Justices Kagan and Powell. But the judicial experience she had is not necessarily conducive to the largely cerebral approach of judging that happens on the Supreme Court.

Jackson hashad a distinguished academic career, having graduated from both Harvard College and Harvard Law School with honors. In the 17 years between Harvard Law School and her first judicial appointment, she had several noteworthy positions in various legal enterprises, including five years as a member of the U.S. Sentencing Commission. Jackson also served as an assistant federal defender in the District of Columbia for three years, during which she enjoyed success as a trial lawyer.

Her first judicial appointment was to the United States District Court for the District of Columbia in 2014, where she served as a district judge for seven years. In June of 2021, following President Biden’s nomination, Jackson was confirmed to replace Merrick Garland on the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

But only eight months later, Biden named her to replace the retiring Justice Stephen Breyer on the Supreme Court. In her eight months on the Court of Appeals, Justice Jackson authored only two opinions.

The practical reality was that Biden nominated a district court judge to a seat on the Supreme Court consisting of nine justices who decide cases by majority vote.

District court is where federal cases begin – where “cases” and “controversies” are first decided. The district judges are the “referees” between the litigants, and sometimes they serve as the decision-makers on the outcome of the cases. There is a significant amount of trial work where the district judge presides alone over the proceedings. Many quick decisions and judgments are made during a trial, often with little time for research or considered analysis.

Even where time and research are available, the district judge is still working “solo” with the assistance of one or more law clerks. The final decision on such motions belongs to the judge alone.

District judges largely operate independent of their peers in the same courthouse. Their decisions are not binding on each other. They preside over their own dockets and make decisions in the cases assigned to them as they see fit.

Under this system, legal mistakes and errors are inevitable. The only requirement for proceedings at the district court level – including trials – is that they be fair. It is not required that they be “error-free.” Only when errors result in unfairness that prejudices one side or the other is the outcome of the case called into doubt.

Appellate courts sit in review of the outcomes in trial courts. They focus on the errors in the case presented. While broader legal questions are sometimes an issue on appellate review, the focus is primarily on the presence or absence of errors in the case in the district court, and whether any identified errors justify altering the outcome in that court.

The Supreme Court plays a very different role. While it does make a judgment about the correctness of the outcome of cases, the focus of the Supreme Court is normally on the broader legal implications for hundreds/thousands of other cases in the future from affirming or reversing the case being reviewed.

The federal district judge often plays the role of interrogator of the attorneys representing each side. Anyone who has been a trial attorney for any substantial period of time in federal district courts understands this. The questioning by that district judge can be hostile, aggressive, condescending, dismissive, humiliating, etc. But that questioning is focused on the facts and specific legal issues presented in that case, and not the broader implications of how the outcome of that case might impact other cases. Part of the reason is because that district judge’s decisions are not binding on other district judges.

Jackson just completed her third term on the court. This chart, which is from the 2024-2025 term, is highly revealing in terms of one of the issues that stands between her and her colleagues – her conduct as a justice is still influenced by her eight years as a district judge, i.e., she spends much more time examining the attorneys before the court than do her colleagues.

The same source has a similar chart for the 2023-2024 Term of the Court, and the numbers are no different.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

Setting aside this quantitative measure, in listening to many oral arguments of the Court this past term, one gets the very familiar vibe from Jackson of a district judge interrogating one counsel or the other to wring out admissions or concessions about the specifics of the case. The focus is on the outcome of the case, and not the broader implications that the outcome might foretell.

Justice Samuel Alito can often present in the same manner, but he spoke less than half the number of words as Jackson. She separates herself from her colleagues both in terms of how much time she is involved in the dialogue and her sharply partisan tenor that gives away what her likely vote will be in pretty much every case with any political implications.

Her rhetoric in dissenting from the Trump v. Casa – “With deep disillusionment, I dissent” – seems an almost unintended peek behind the curtain of her thinking. What the majority did was take away one of the most powerful weapons possessed by a district court judge to shape how a case goes forward from the outset.

The progressive activist inner district judge in her – who seeks only to “do right” – is protesting that loss.

WILLIAM SHIPLEY

Read the full article here