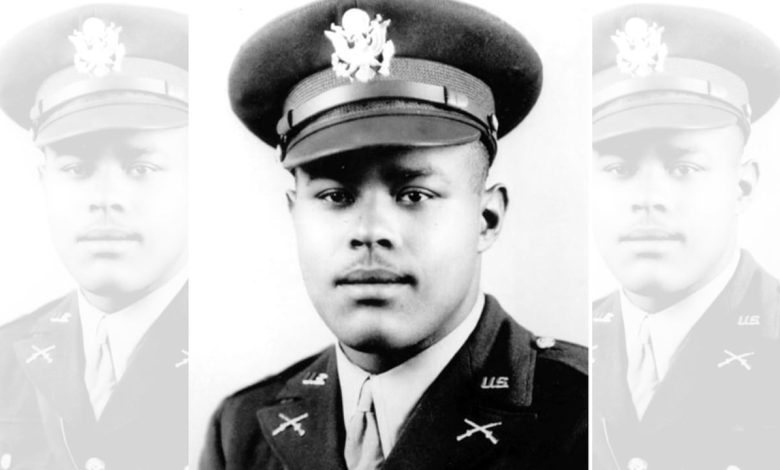

Why this MOH recipient’s stand in France is the stuff of WWII legend

War heroes seldom choose their battles. All they can do is rise to the occasion. For 1st Lt. Charles L. Thomas, the defining moment in his military career was a company-sized fight five miles from the German border.

It was Dec. 14, 1944.

Just two days later, however, the battle’s strategic importance would be relegated to the sidelines amid the mammoth German counterattack in the Ardennes Forest soon known to the Americans as the Battle of the Bulge.

When Charles Leroy Thomas was born on April 20, 1920, there were few opportunities for Black Americans in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama.

His family, therefore, sought better prospects by joining the Black exodus northward, settling in Wayne, Michigan. After graduating from the Cass Technical High School in 1938, Thomas worked as a molder at Ford Motor Company while learning mechanical engineering at Wayne State University.

With the United States’ entry into World War II, Thomas was drafted at Fort Custer, Michigan, on Jan. 20, 1942, training at Camp Wolters, Texas, and subsequently working at its infantry replacement center.

He was later redeployed to Camp Carson, Colorado, where he was assigned to the newly formed 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Although it was a segregated unit, with most of its officers being white, the 614th represented a new specialty — tank destroyer — which the Army was eager to organize against Germany’s panzer divisions.

Thomas was a sergeant by then, but considering his outstanding performance combined with the new corps’ need, he was encouraged to apply for Officer Candidate School Class 21, graduating on December 18 and receiving a second lieutenant’s commission on March 11, 1943.

Shipped to England on Aug. 27 and then deployed to the Normandy landing ground at Utah Beach on Sept. 7, 1944. It wasn’t until that November, however, as part of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Third Army, did the 614th have its first engagement with the enemy.

On Dec. 14, 1944, Thomas was a first lieutenant when he was put in command of 3rd Platoon, C Company, 614th battalion, as part of a composite of several other units totaling 250 troops under Col. John P. Blackshear.

Eponymously dubbed Task Force Blackshear, its mission was to seize the town of Climbach, France. Thomas led the advance from an M-20 armored command vehicle.

Facing TF Blackshear were elements of the 21st Panzer Division, a veteran unit formed in 1941 as part of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, but which had been badly mauled in Normandy and was consequently placed by Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt at the sidelines for flank defense in the coming counterattack.

As TF Blackshear made its way uphill toward the town, it came under armor and artillery fire — Thomas’ M20 was the first vehicle hit.

Thomas was wounded by metal splinters and glass, but his first thought was to help his wounded crew get clear of the disabled car.

This made him an easy target for a German machine gun, which opened fire and hit Lt. Thomas in the chest, left arm, and legs, according to the National World War II Museum.

Despite his severe injuries, Thomas carried on, directing his men to deploy their anti-tank guns, taking on the Germans under direct fire, in an open field.

The Germans, recognizing that the American gunners could unhinge their position, laid down concentrated small arms, machine gun, artillery and mortar fire on them. Over the next four hours the 3rd Platoon traded rounds with its experienced but war weary opponents.

“But the Americans,” writes the National WWII Museum, “did not flinch.” Although losing two of its four guns and more than half of its men — three killed and 17 wounded — “those who could still stand simply shifted to crew the other weapons and kept inflicting punishment on the Germans so that the 103rd Division GIs could move forward.”

Aware of the seriousness of his injuries, Thomas finally contacted the senior 3rd Platoon member still standing, briefed him on all he knew of the situation and only then did he consent to evacuation.

But the Germans kept coming.

Surging out of a nearby forest to launch a direct assault, the enemy was determined to wipe out the remaining two guns. Not a single American man fell back amid the onslaught, rather they began engaging the Germans in direct combat.

One soldier, according to the museum, mounted a burning half-track and manned the vehicle’s .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy.

Despite ammunition stocks running low, the Americans were able to successfully fling the Germans back, and, according to the 103rd Division, “precluded a near catastrophic reverse for the task force,” and ensured the capture of the French town.

The 21st Panzer, worn down, abandoned Climbach and withdrew to the Siegfried Line along the border.

For the 614th, it was mission accomplished, with the 3rd Platoon collectively awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation.

And while Thomas convalesced in the hospital, his career was undergoing action behind the lines.

In January 1945 he was promoted to captain and on February 20 he received the Distinguished Service Cross from Col. Blackshear, who was aware that Thomas’ skin color was all that stood between him and a higher honor.

For his own part, Thomas dismissed the matter when he returned to a hero’s welcome in Wayne.

“I know I was sent out to locate and draw the enemy fire,” he explained, “but I didn’t mean to draw that much.”

Thomas retired from the Army as a major on Aug. 10, 1947, married in 1949 and had a daughter and a son. He worked thereafter as a missile technician at Selfridge Air Force Base, Michigan, and as a computer programmer for the Internal Revenue Service.

He died of cancer on Feb. 15, 1980. He is buried in Westlawn Cemetery, in his adopted hometown of Wayne.

Charles Thomas’ multiple careers were destined to a last twist, however. On Jan. 13, 1997, his niece came to the White House, where President Bill Clinton conferred upon him and six other Black American heroes of World Wars I and II DSCs upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

At the ceremony, one of his comrades, Lt. Claude Ramsey, remembered: “The victory at Climbach in December ’44 belongs to Capt. Charles Thomas and the company he led into that valley where they would be like clay pigeons in a shooting gallery. Charles had several things going for him. His men believed in him and they were proud of their unit and their ability. They were good, damned good.”

Read the full article here